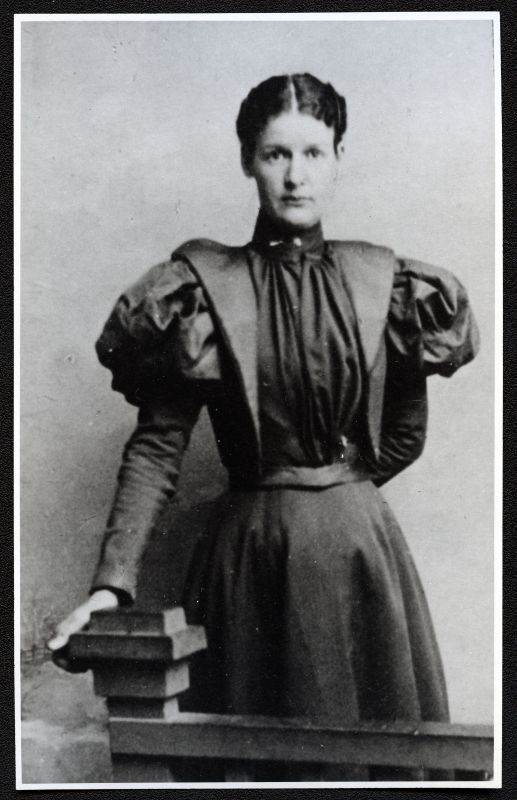

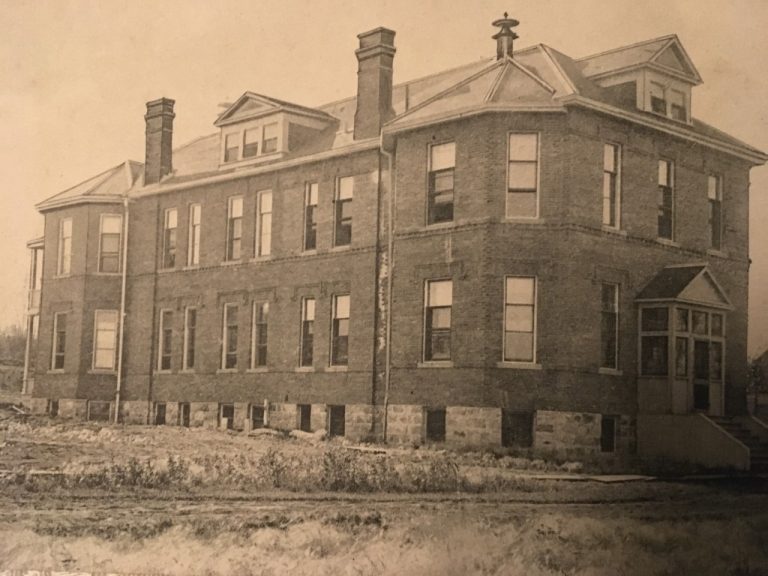

In 1933, when the forty bed Victoria Hospital was in run-down condition and deeply in debt, Jean Harry appeared on the scene and, within a decade, the hospital was restored and operating in the black. Perhaps not all the credit for this turn-around can be laid at the feet of this amazing woman, but certainly she deserves her fair share.

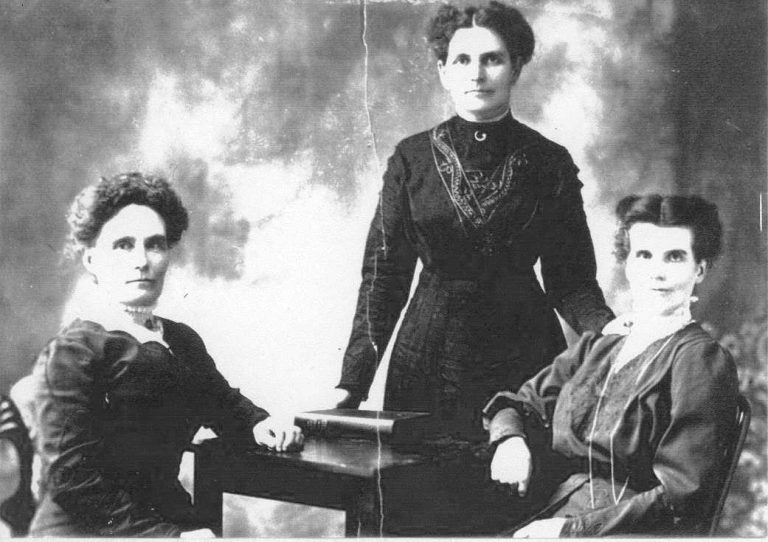

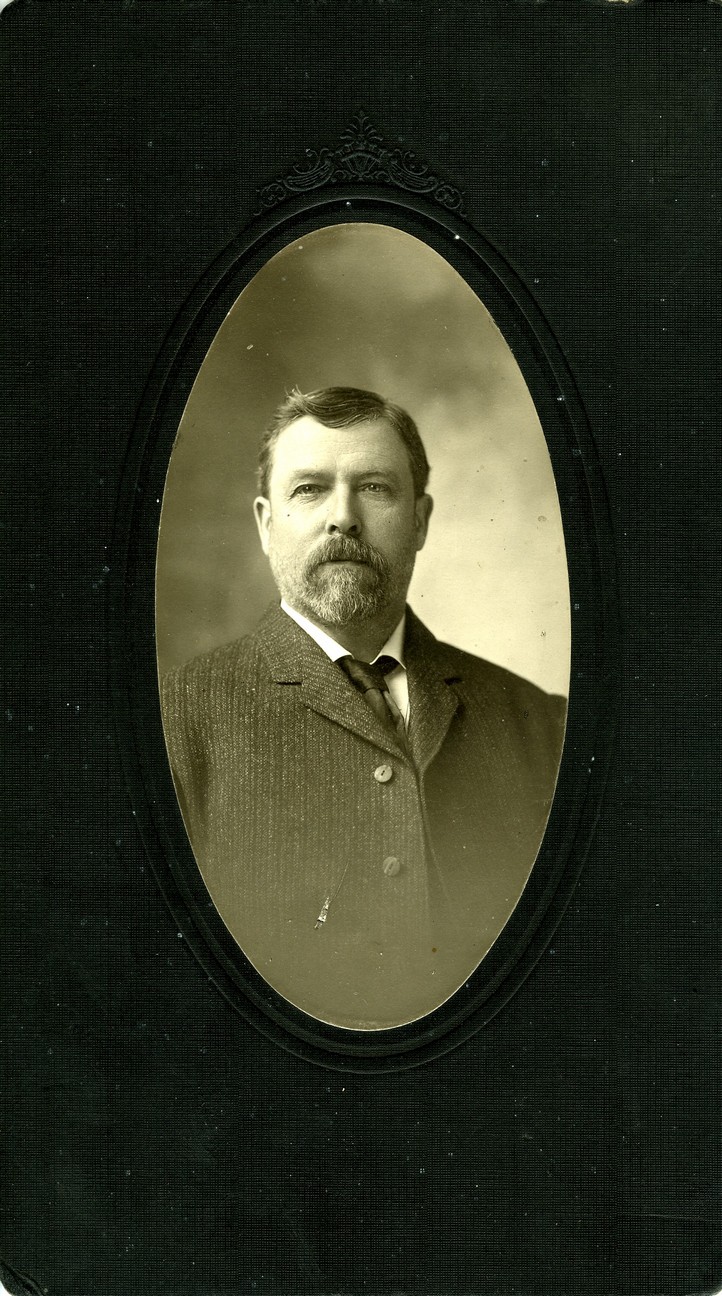

Jean Harry was born on June 9, 1888, in Fort MacMurray, North West Territories, the second of eight children born to her parents. Her father, Isaac Cowie, was the Chief Trader of the Hudson’s Bay Company in that community. Her mother, Margaret Jane Sinclair, had grown up in the Red River Settlement’s community of St. Andrew’s.

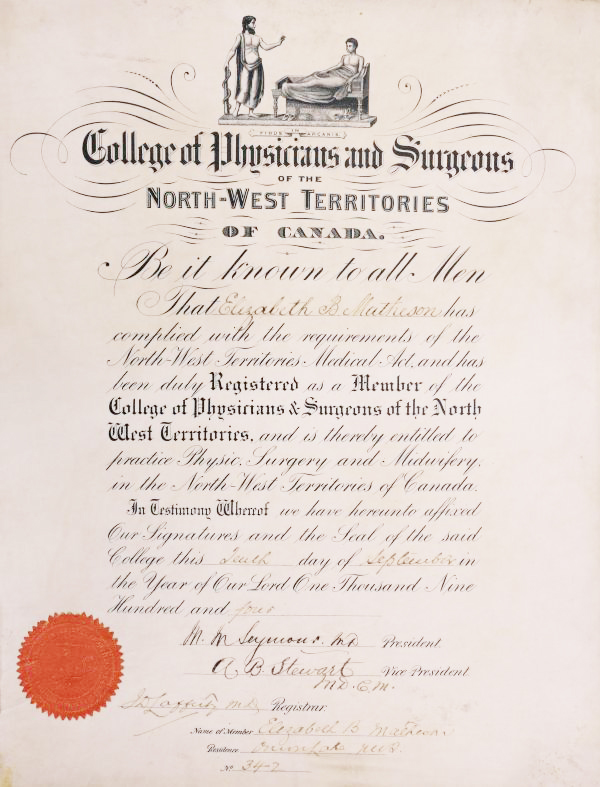

Cowie was originally born in Lerwick, Shetland, although several members of his family practised medicine in the Scottish city of Edinburgh. His wife was also the offspring of a fur trade family, the Sinclairs being associated with the North West Company, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and the ‘free’ fur traders.

Cowie had originally studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh but, after completing only one year of his education, he took a position with the Hudson’s Bay Company and moved to Fort Qu’Appelle in what is now Saskatchewan. His wife was born at Fort Edmonton, although she was educated at Miss Davis’s School at St. Andrew’s, Red River Settlement, before being “finished” at St. Mary’s Academy in Winnipeg.

Shortly after her birth, Jean’s father undertook his final three-year contract in the employ of the Hudson’s Bay Company, accepting a posting at Ile a la Crosse in what is now northern Saskatchewan. Thus it was that Jean spent her first three years in that community. Once this contract was completed successfully in 1891, Isaac Cowie retired from the fur trade company, moving with his family and settling in Edmonton, where he became the first secretary of its Board of Trade. In 1896, he ran successfully for the Edmonton town council. In 1901, the family relocated again, this time to Winnipeg.

As a result, Jean was educated from kindergarten to about Grade Five at St. Joachim’s Academy in Edmonton, and then (like her mother) “finished” at St. Mary’s Academy in Winnipeg. While at the latter institution, she specialised in music, and dreamt of becoming a concert pianist. This, however, was very much an impracticable dream; nursing was very much more realistic.

However, one had to be twenty-one years of age to enter nurse’s training, and Jean was too young. Using her competence as a musician, she taught piano until such time as she was of the appropriate age, finally entering the Winnipeg General Hospital School of Nursing, an institution founded, in part, by her mother’s forebears.

Jean was found to be ambidextrous, perhaps in part due to her training as a pianist, and this capability turned out to be of great value as a scrub nurse. This in turn helped her to win the gold medal for proficiency in surgical techniques in the school’s graduating class of 1912.

Immediately after graduation, she did special nursing, and was on the staff of the Royal Inland Hospital in Kamloops, British Columbia when the First World War broke out. Jean paid her own way to England, where she joined the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Nursing Service. While overseas, she married Wilmot Earl Harry, a man she had known before she left Canada.

Harry, although an American, was an original member of the Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry (number 644 on the regimental roll). He was wounded in the first battle at Ypres, leading to his transfer to the Royal Engineers, where his training as a civil engineer came in useful. Harry won the Military Cross and Bar with the Engineers, and became a staff officer in Russia after the war. This was the first of several assignments which took the couple to many other countries before they returned and resettled in Canada.

Jean, of course, earned her own service medals during the war, and was entitled to wear them as well as the George V Jubilee Medal, awarded to her in 1935 for public service.

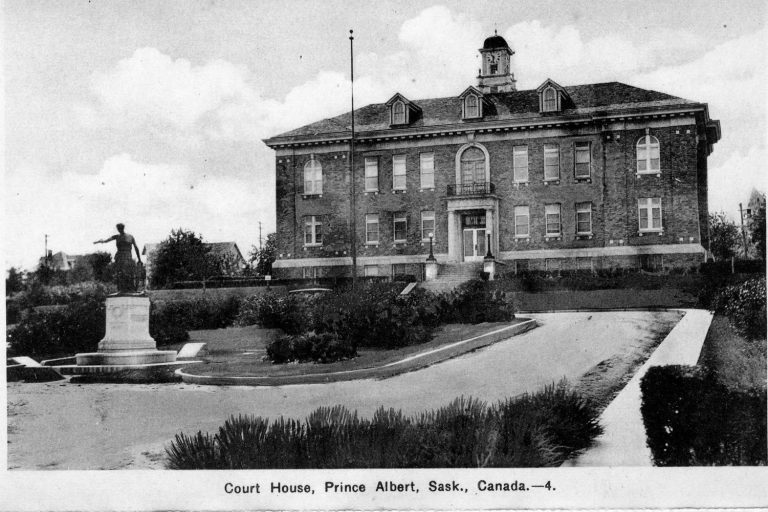

Upon their return to Canada, Jean served as teaching supervisor at the Winnipeg General Hospital School of Nursing before they moved in 1933 to Prince Albert, where she became the superintendent of both the hospital’s nursing administration and its school of nursing.

A training school for nurses had been founded shortly after 1900. According to annual reports (which tended to be repetitive year after year), nurses received a very thorough, scientific, yet practical training. As a result, they had a reputation as being very efficient, skillful, and of the highest degree of caring. One annual report noted the many changes and improvements through the years, both in procedures and routines. Especially noted was the improvement in charting and in operating room techniques.

A report from 1953 noted that “at one time in the history of our hospital there was a slump in nursing technique with records of poor nursing care”. But “under the present leadership of Mrs. J.S. Harry and her efficient, faithful and practical service of the past 19 years, the well staffed and efficient personnel…Prince Albert and surrounding districts have every reason to be proud of the Voctoria Hospital and Training School.”

Jean Harry was admittedly a hard taskmaster. She told her students that nobody would ever be harder on them than she would. But when they left her hospital, they were capable of handling any nursing job that came their way.

On one occasion in the 1940s, she was approached by a junior nurse who suggested that the students should wear chevrons on the sleeves of their blouses to indicate the year of training in which they were. First year students would wear one chevron, while the second-year students would wear two, and the third-year students would wear three. Her terse response was that when she was a senior on the ward “nobody mistook me for an intermediate.” At some point later in her career, she apparently relented as the chevrons eventually did appear.

Jean did not confine her training to nursing techniques. For many who had had no social advantages, she taught the little touches, everything from table napkins and more, which would help them progress through the world which it was likely they were likely to encounter.

Jean Harry retired from hospital nursing in 1959. By this time, her husband had died, as had her second son, William (Billy). Her husband, Wilmot, had never really recovered from the effects of the Great War, and he died on Jean’s birthday in 1941. Billy, who had followed his father into the Princess Patricia Light Infantry and served in World War Two, had transferred into the First Special Services Force before he was killed in action in France in 1944.

Upon her retirement from hospital nursing, Jean went on to the Saskatchewan Registered Nurses’ Association inactive list. She moved to Maple Creek, Saskatchewan, where her son, John, was a doctor. However, in her late 70s, she renewed her active registration in order that she could assist John in his medical practice.

Jean Harry continued learning throughout her entire life. In 1957, when she was almost 70, she passed the American Association of Hospital Administrators diploma course. She also learned to drive a car when she was past the age of 60, an experience which nearly drove her driving instructor to distraction. Realising the menace she had become on the roadways, Jean voluntarily gave up her licence in 1969 at the age of 81.

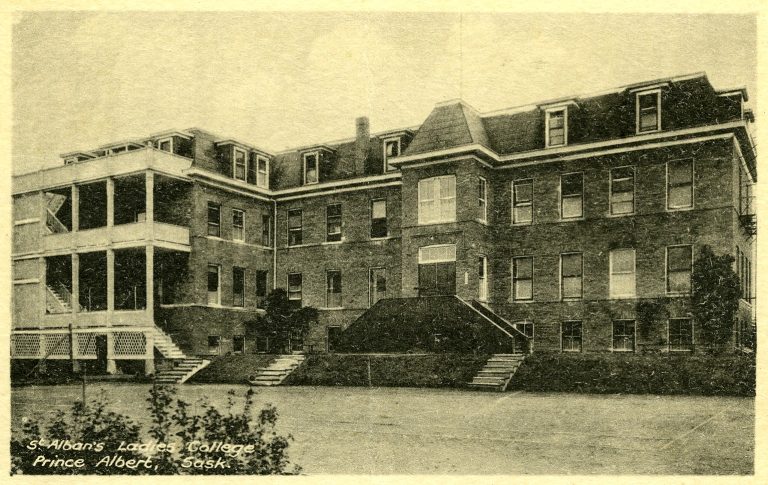

That was the year when, in recognition of her outstanding contribution to nursing in the province, the Saskatchewan Registered Nurses’ Association presented her with a life membership. It was also the year when Jean started the study of the German language in the hope that knowledge of it would be useful on a tour of Germany. Jean Harry spent the remainder of her allotted years in Maple Creek. She died in a nursing home on Feb. 11, 1982, and was buried from St. Alban’s Cathedral. The honourary pallbearers included the likes of Doctors Metro Surkan, Orville Hjertaas, Park Rich, Glen Green, and Donald Chipperfield. A life member of Prince Albert’s Royal Canadian Legion, her flag draped coffin was lowered into the ground at St. Mary’s cemetery, where she rests amongst so many pioneers of Prince Albert and area.