by Fred Payton

Well, that’s done and dusted. Canada’s 44th General election is in the rear-view mirror. Not that Prince Albert and area has had the option to vote in all 44 elections; nor was this election conducted under the same terms as the first Canadian General election.

An act conferring on women the right to vote on the same basis as men was passed in 1918, and the Dominion Elections Act was passed in 1920. This Act of Parliament consolidated the elections process which previously had allowed for elections to be conducted in each province according to the regulations applicable in the individual provinces. Not only did the Act of 1920 result in an assurance that elections would be conducted in the same manner everywhere across the country, under the newly created position of a Chief Electoral Officer, but it also allowed for advance voting in each constituency. As a result, the election of 1921 was conducted under the same rules in each electoral district, and women were able to vote in every constituency.

Although women had the right to vote, it was not until 1953 when a woman would allow her name to be on the ballot in Prince Albert. In that year, Phyllis Clarke ran for the Labor-Progressive Party, garnering 1.3% of the total vote, as opposed to the 44.1% obtained by the victorious candidate. She later ran in Toronto-Davenport, losing to Liberal Walter Gordon in 1962, as well as unsuccessfully for the Toronto Board of Control. Clarke was described in her 1988 obituary as a devoted socialist, trade unionist, feminist, community activist, and teacher.

Although people in Prince Albert are quick to point out that it was John Diefenbaker, the Man from Prince Albert, who ensured in 1960 that all registered First Nations persons had the right to vote, that right had been conferred on the Inuit in 1950.

Teens were able to vote for the first time in 1972, after the voting age was lowered from 21 to 18 in 1970, and inmates serving less than two years were allowed to vote beginning in 1993. As of 2002, all inmates were allowed to vote. As a constituency with so many correctional facilities, it likely came as a relief to some to realise that inmates’ ballots would be counted in their home community rather than in the Prince Albert electoral district.

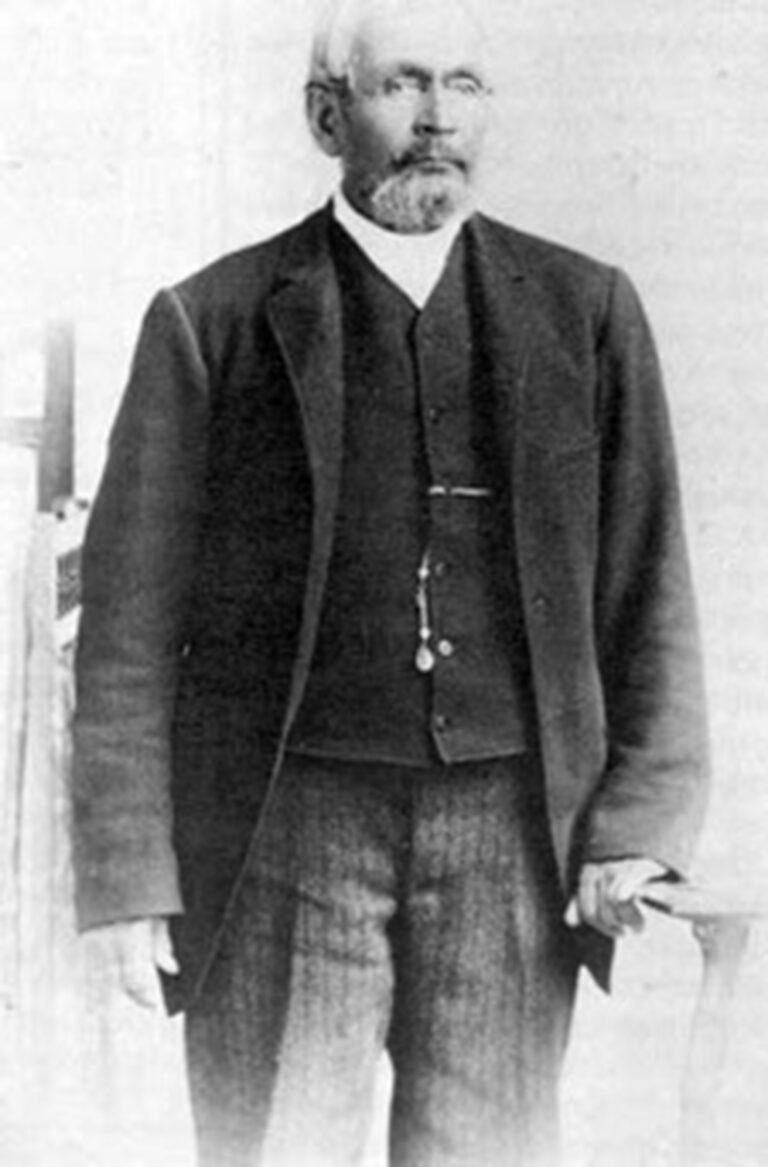

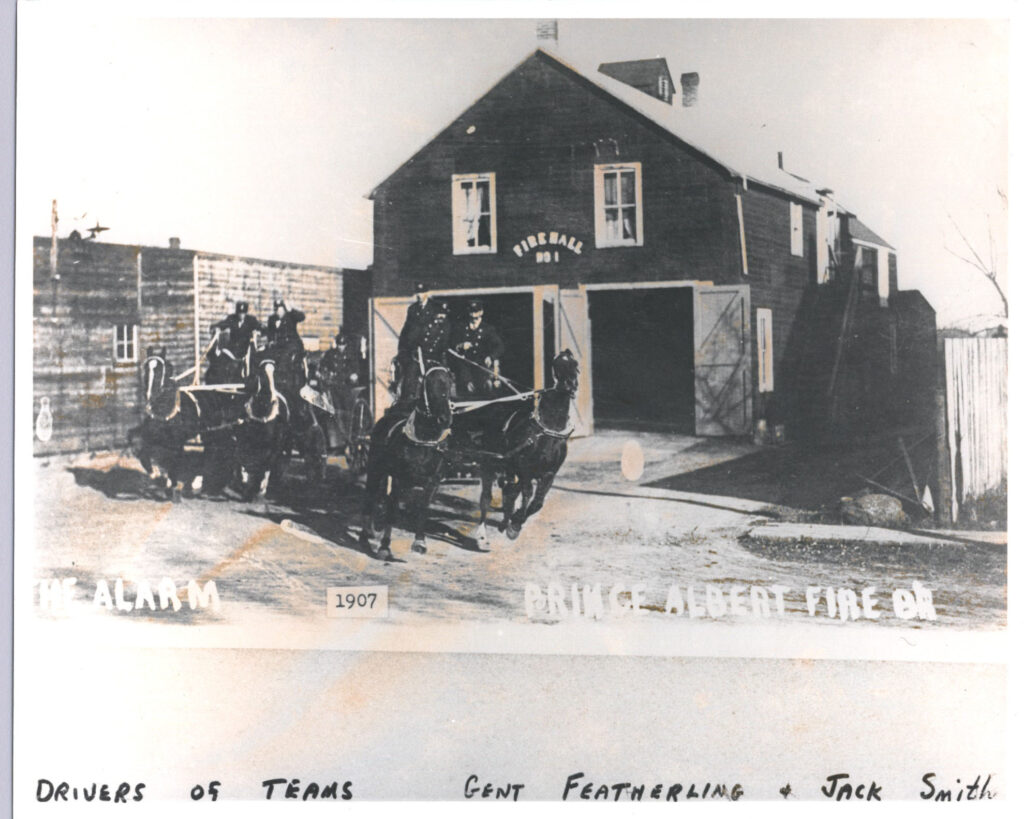

When Canadians first voted, the people of Prince Albert and area were not even Canadian citizens. Local people did not become Canadians until July 15th, 1871, when the country of Canada officially purchased Rupert’s Land, including Prince Albert and area, from the Hudson Bay Company. Even then, they did not become electors of Canada. It was not until 1881 when our citizens had elected representation. It was that year when they were able to vote in the Lorne District for a representative on the North-West Council. Our first elected representative was Lawrence Clarke who, in the election held on March 23rd 1881, defeated Captain Henry S. Moore by a count of 250 to 143.

Clarke was well known, having been a Chief Factor with the Hudson Bay Company and a strong supporter of development for the Prince Albert settlement. Moore, who had opened the first steam grist and sawmill in Prince Albert in 1877, was also a strong community supporter, and was later responsible for the establishment of the ranching industry in this area when he imported over 200 cattle from the Bow River. He was also later responsible for the leadership of one of Prince Albert’s volunteer cavalry units which were established as protection in response to the 1885 Resistance.

In 1883, Day Hort MacDowall was elected locally to the North-West Council, serving until 1885. Interestingly, although a business partner of Captain Moore (who had run as a Liberal), MacDowall ran as a Conservative. Owen E. Hughes, a general trader, was elected in 1885 and served until 1888.

The Legislative Assembly of the North-West Territories was established in 1888, and Prince Albert was represented in that Assembly by several well-known individuals, including J. F. Betts, William Plaxton, Thomas McKay, J. Lestock Reid, T. J. Agnew, and Sam McLeod.

In 1887, Prince Albertans had their first opportunity to vote for a member of the House of Commons. D. H. MacDowall served from that first election until 1896. In the election that year, Wilfrid Laurier ran in Prince Albert in an effort to establish a western Canadian Liberal presence, but although he won the local seat by a margin of 44 votes, he chose to represent the Quebec-East seat which he had also won. Electoral rules in those days allowed individuals to run in more than one electoral district. The by-election which resulted due to Laurier’s decision resulted in the election of Thomas Osborn Davis, who served from 1896 until 1904. Prince Albert returned another Liberal, J. M. Lamont in 1904, who served until 1905. Lamont was followed by G. E. McCraney (1905 – 1908), and W. W. Rutan 1908 -1911, both Liberals. In 1911, James McKay was elected, and he sat in the Commons until 1914.

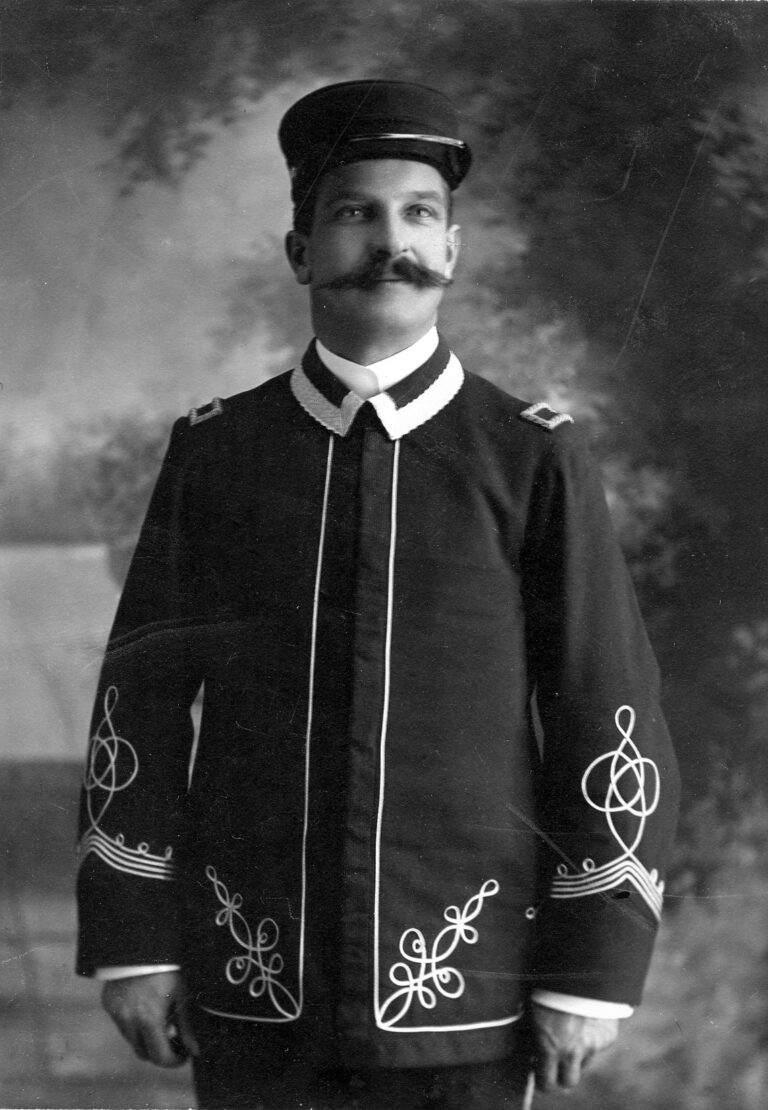

Sam Donaldson, who had served as mayor of Prince Albert. replaced McKay as the Conservative candidate in the 1915 election and was victorious. In 1917, he was defeated by the Unionist candidate, Andrew Knox, who was again elected in the 1921 election when he ran as the Progressive candidate. Knox, a popular farmer from the Colleston district, had been a district director of the Saskatchewan Grain Growers Association, although he displayed his greatest strength in the city, while Liberal candidate, Samuel McLeod, was strongly supported in the French-speaking settlements and the culturally mixed towns such as Wakaw, strength that continued for them until the election in 1945.

The next General Election, which was held in 1925, led to a major change in Prince Albert’s influence nationally, although the impact was not seen until the following year. Charles McDonald, who had served as Prince Albert’s member of the provincial legislature, had chosen not to seek re-election provincially, but rather to seek the local federal seat for the Liberal party. He won a clear majority in the 1925 election, gaining more votes than Knox and John Diefenbaker combined.

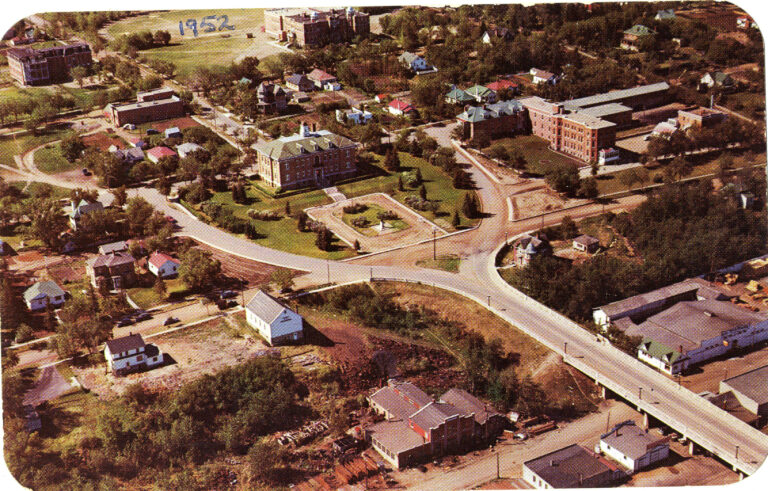

But the Liberal leader, William Lyon MacKenzie King, was defeated in his riding of York-North. McDonald agreed to forego his seat in the House of Commons in order for MacKenzie King to run in Prince Albert. The Liberal leader made several promises to accommodate this decision. This first of these was the establishment of a national park in the vicinity, while the second was to ensure McDonald be given some preferment for his withdrawal. The first promise was met when Prince Albert National Park was opened in August, 1928. The second promise took some time to fulfill, but in 1935 McDonald was appointed to the Senate for the province of British Columbia. Unfortunately for McDonald, by this time his health was poor and he died before he could be sworn in as a member of the Red Chamber. He is the only Canadian elected to the House of Commons, appointed to the Senate, while never having taken his seat in either.

MacKenzie King served Prince Albert as its Member of Parliament from 1926 until 1945. His re-election in the General Election held in June of that year was expected to a certainty. But the local people had become impatient with the low wages and poor working conditions brought on by the war time controls of the Second World War. The local C.C.F. candidate, a Shellbrook farmer by the name of E. L. Bowerman, touted the promises of his party which promised social security, medical care, and a national housing plan. Although King led the polls on election night, when the ballots of the servicemen serving overseas were counted, Bowerman had won by 129 votes.

Four years later, in the next General Election, the Liberals were able to re-take Prince Albert once again. Francis “Frank” Helme, an implement dealer, defeated Bowerman in the Liberal landslide victory of that year. It would not be for another fifty years that the Liberals would win a Prince Albert and area riding.

In 1953, a coalition of party supporters encouraged John Diefenbaker to seek the Progressive Conservative nomination in Prince Albert. His success in that election was the first of a string of ten electoral victories for Diefenbaker in Prince Albert. Diefenbaker served as Prime Minister of Canada from 1957 until 1963, and was still the sitting member for the constituency when he died in his suburban Ottawa home in Rockcliffe on August 16th, 1979.

The by-election required as a result of Diefenbaker’s death was won by the New Democratic candidate, Stan Hovdebo, a local educator. He went on to two successive General Election victories in Prince Albert, from 1979 to 1988. When the riding was re-distributed prior to the 1988 General Election, Hovdebo chose to run in the Saskatoon-Humboldt riding where he was again victorious. He retired from active politics prior to the 1993 General Election.

As a result of a change in electoral boundaries prior to the 1988 General Election, the Prince Albert constituency became known as the Prince Albert-Churchill River constituency. Rather than its boundaries running east and west, the constituency ran north and south. Five candidates contested the riding, with the New Democrat candidate, Ray Funk, winning the seat by a margin of over 9,600 votes over the second place Progressive Conservative candidate.

In the 1993 election, the Liberals managed to win the seat in a contest which featured eight candidates, including two independent candidates. Gordon Kirkby, who had been the mayor of Prince Albert, received slightly more than 2,500 more votes than the incumbent, Ray Funk.

The Prince Albert riding was re-created from the Saskatoon-Humboldt and Prince Albert-Churchill River ridings in time for the 1997 General Election. Derek Konrad represented the constituency for the Reform and Alliance Parties from 1997 until 2000. Brian Kirkpatrick won the nomination for the Alliance Party prior to the General Election in 2000, and held the seat until 2008. From the 2008 election until the 43rd Parliament was prorogued, Prince Albert was represented by Randy Hoback of the Conservative Party.

I have met all of our Members of Parliament from John Diefenbaker on, although I knew some of them better than others. Although I did not agree with each of them on everything they stood for, I recognise that they all had a desire to make Canada a better country. They all felt that they could make the lives of Canadians better. For that, I can respect them.