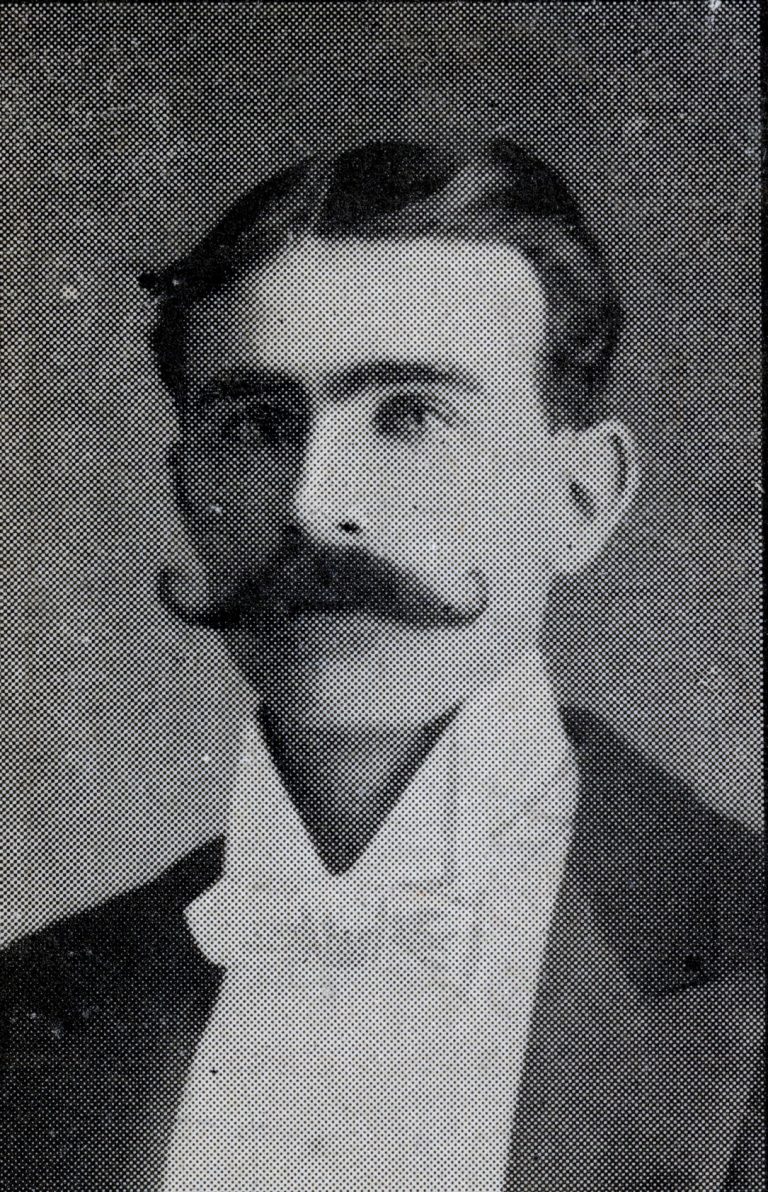

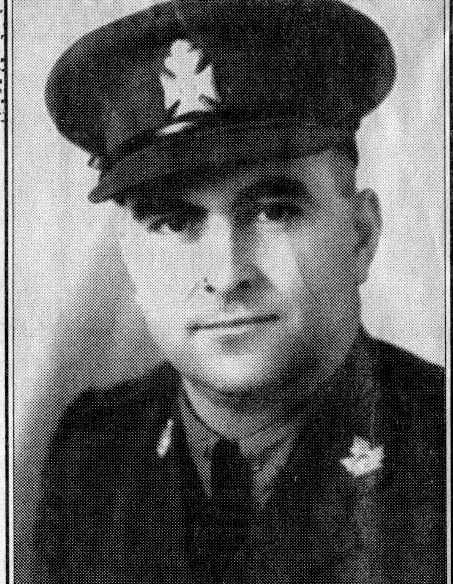

Fred Payton

Prince Albert Historical Society

I wonder how many of the readers of this column will remember Miller’s Hill? Of those who do recognise the name, I would be curious to know how many might be aware of from where the name came.

William Miller arrived in Prince Albert in July 1873. Born in Berwickshire, Scotland in 1832, he was the second son of Richard and Margaret Miller. He emigrated to the Genesee Valley, New York in 1853, and in November of that year moved to Upper Canada, living in the Wroxeter area of what is now Ontario. He married Jessie Ann Hume in 1859, after having established a flax mill on the Maitland River in Huron County.

When the mill was destroyed by fire, Miller, his wife, and five children moved west, seeking a new life on the land which he had heard was fertile farm land. They settled at a place which became known as Rockwood, near what is now Winnipeg.

After farming there for a few years, Miller realised that many of the settlers from the area were moving to the Saskatchewan Valley. A family by the name of McBeth, who were not only neighbours but also friends, were moving to Prince Albert, so Miller sold his farm and joined them in the move.

In the book, “the Voice of the People”, Mrs. Margaret MacKenzie, Miller’s nine year old daughter at the time of their move from Wroxeter to Rockwood, provides a vivid description of the original move to what is now Rockwood, and the move from there to Prince Albert. She tells of being warned off by four men who were “sent by Riel” prior to their arrival at Fort Garry during the 1870 uprising which led to the creation of Manitoba. She also tells of the difficulties they experienced in trying to cross the fast flowing south branch of the Saskatchewan River with their livestock, and of their meeting with Chief Beardy, who demanded payment for the passage of their party through the lands he claimed to control.

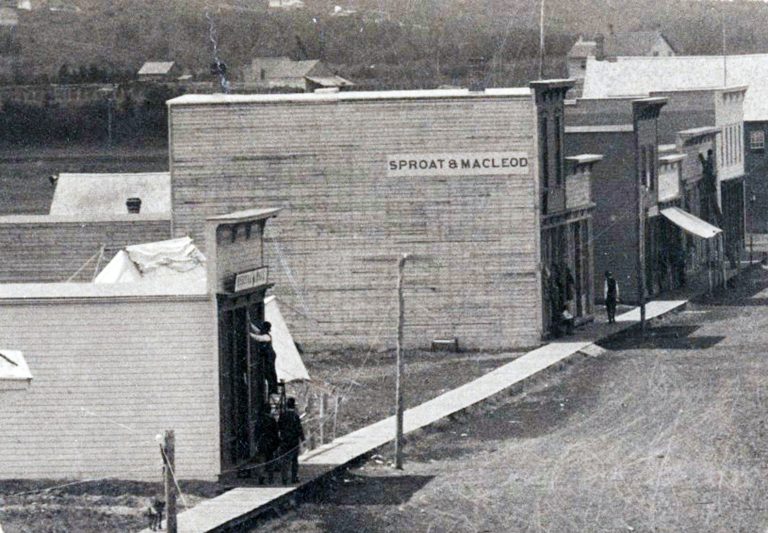

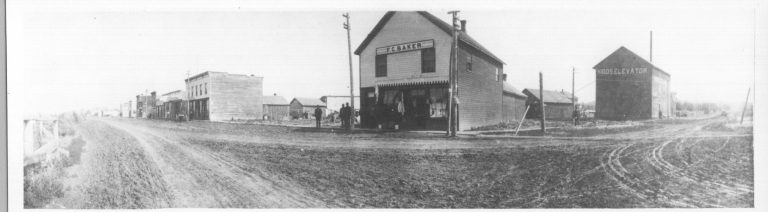

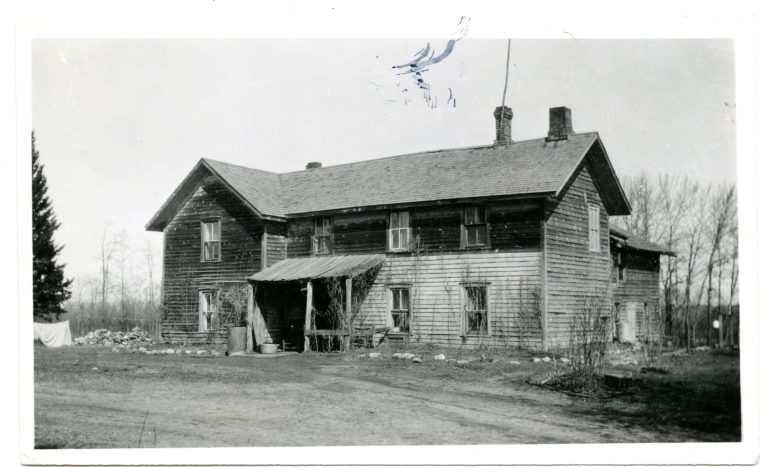

William Miller and his family settled on land just to the east of the Hudson’s Bay Company reserve. They were, in fact, squatters, as there was no land registry available to the local settlers at that time. Miller’s original home was built on the river flat, near the North Saskatchewan River. However, after a sudden flood two years after they had built their home, he determined that he should move up the hill and build a new house in a safer location. Mrs. MacKenzie describes the effects of the flood, as well as the tragic results for others, in her narrative previously mentioned.

In 1879, Miller’s wife, Jessie, died, leaving him with nine children, a tenth dying at about six weeks of age soon after the death of its mother. William Miller married his second wife in June 1882. She had come from Scotland in 1881. They had seven more children, many of whom continued to reside in the Prince Albert area.

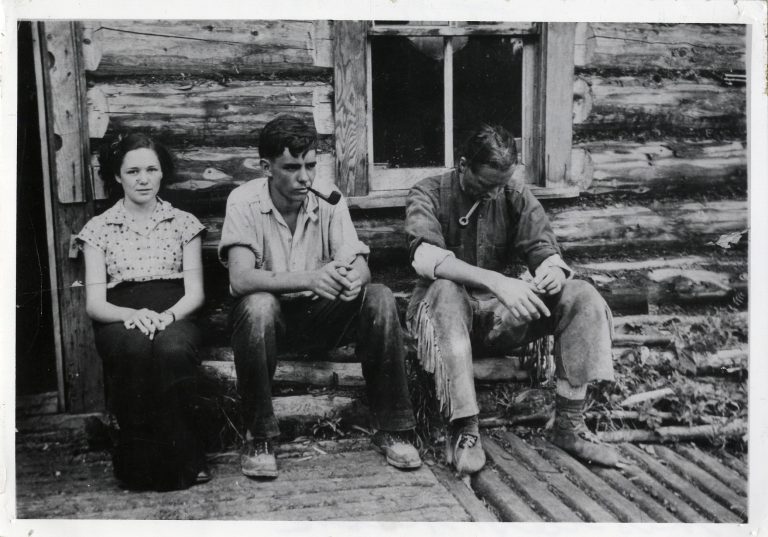

The house on Miller’s Hill was known as a gathering place, and Miller was known for being sociable and as a friend to many a newcomer. One account, prepared by an anonymous person, described the Miller house on New Year’s Eve. All were welcome, he wrote, and the house would be filled by eight or nine o’clock. Dancing occurred until eleven o’clock, when a lunch would be served. Then, time would be spent in recitations and singing, always with plenty of laughter. William Miller always insisted that any guest who had come from a distance should stay for breakfast before starting for home.

Miller was also very active in public affairs, participating in anything which was considered to be for the benefit of the community. Active in the Presbyterian church, he ensured that his children always went to Sunday School. One daughter, Mrs. A.E. (Georgina) Freeborn, recalled how on Sunday nights her father would take out the family Bible, have each child read a verse, and then would read a prayer from the prayer book. After the Knox Presbyterian church was built in Goschen, the family were regular attenders.

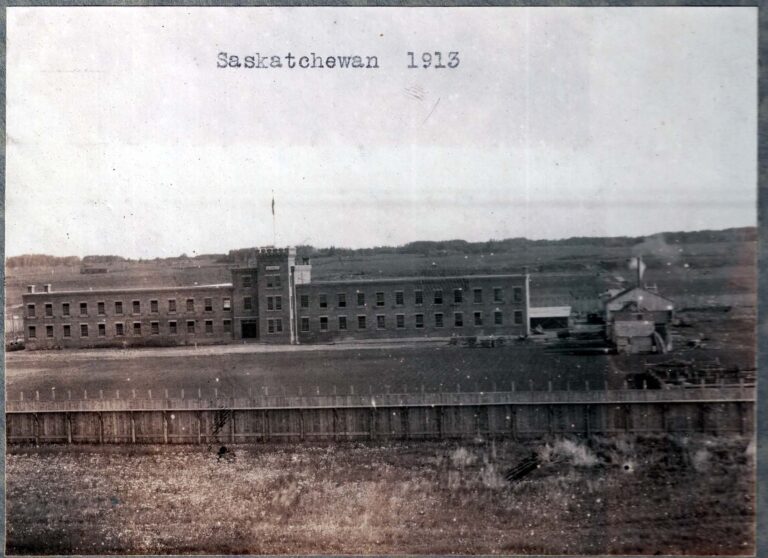

As a result of the lack of proper land registration, many settlers had their developed property turned back to the Crown when a proper survey was finally completed. With no federal representation available to them, members of the farming community organised a Settlers’ Rights Association in 1883. Given his ability to articulate their problems, Miller was elected president of the committee.

In 1884, at the urging of William Miller, the Lorne Agricultural Society was established. Not only did it function as an organisation concerned with farming, but it became a local council with access to government authorities.

When the Prince Albert East School District was organised, it was William Miller who was elected president, a position which he held until his death in 1904. He was also one of the four men who were responsible for the construction of the first school in the community.

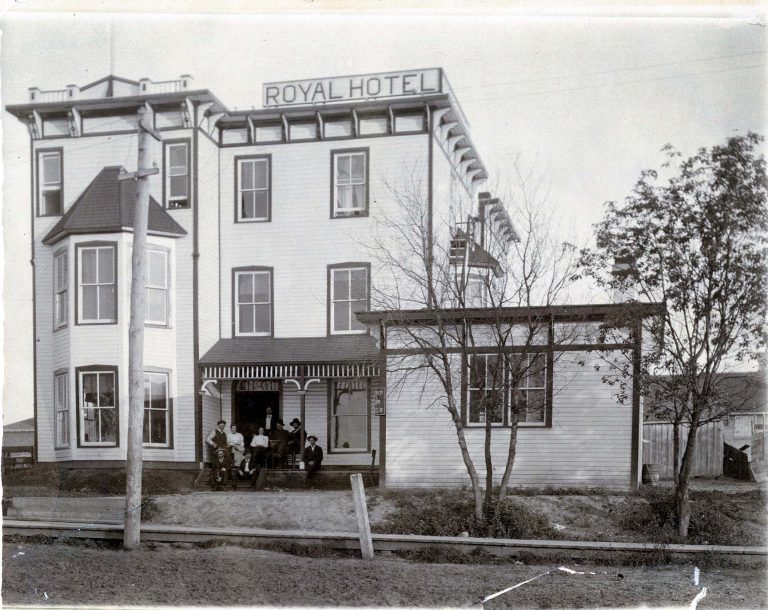

The lower land which Miller had originally farmed, and on which he had built his first house, was eventually given to Captain Moore on which to build a steam driven flour and lumber mill. The fifteen acres which Miller provided were later sold to the Prince Albert Lumber Company.

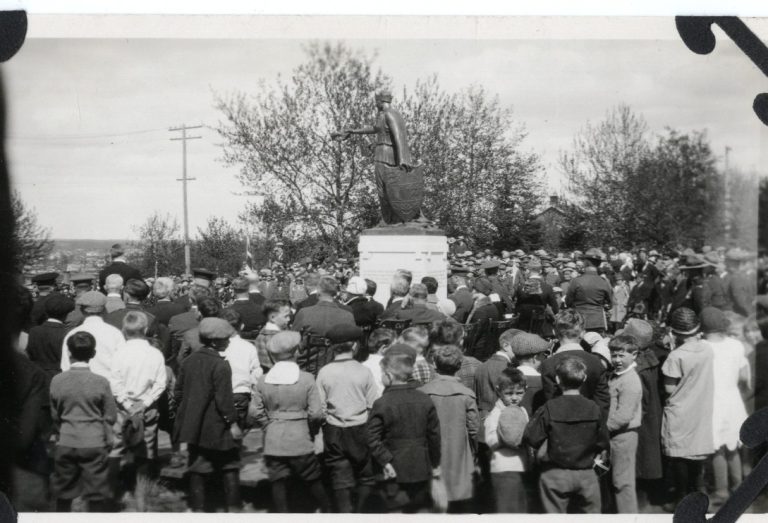

As noted, William Miller died in 1904. His second wife lived until 1930. However, their accomplishments continue to live on, and are remembered in the memorial park, Miller Hill Park, named for him.

Happy New Year everyone!

fgpayton@sasktel.net