One of the pleasures I find when travelling is the opportunity to visit second-hand bookstores. One never knows what treasures await one in such shops. I have a favourite such bookstore in Ottawa, located on the corner of Bank and Frank, and on every trip to our capital city I will head into the back corner of the basement to search through their extensive collection of Canadian history and biography books. One such visit resulted in quite a red-letter day when I came upon two books referencing two individuals who not only played a significant role in Prince Albert’s early history but who are both buried locally in St. Mary’s Anglican cemetery.

Referenced in John Edward Weems’ book “Peary – the Explorer and the Man” is a man of whom I have childhood recollections, George Carr. In the 1890s, Carr travelled with Admiral Peary on his initial voyage in search of the North Pole. Although they did not attain their goal during that attempt, Carr’s involvement in the expedition is well chronicled. It was not until 1912 that Carr moved to Prince Albert, a place he made his home. Active in many aspects of the life of the city, from business to politics to sporting activities, George Carr’s life is well worth delving into.

The second individual about whom I found information in that Ottawa bookstore was Jacob Beads (sometimes spelled Beeds). Beads was a member of Dr. John Rae’s 1853 expedition to investigate what had happened to the Franklin expedition of 1845. Ken McGoogan’s book “Dead Reckoning: the Untold Story of the Northwest Passage” provides information regarding the Franklin search for the Northwest Passage, as well as Dr. Rae’s attempts to locate the ships Erebus and Terror. Although they were largely unsuccessful in discovering what had happened to the ships and their crews, Queen Victoria was sufficiently impressed with their efforts that she awarded members of the Rae expedition with medals and cash in pounds sterling. The medals are inscribed “For Arctic Discoverers, 1818 – 1855”.

An expedition had been organised to search for the missing party of Sir John Franklin who had not reported for nearly a decade and was considered to be missing. The expedition consisted of twelve men under the direction of Dr. Rae, with an Inuit guide. They left Lake Winnipeg and passed through The Pas, journeying to the Churchill River and Hudson Bay. Freezing weather hampered the party as they went further north to Chesterfield Inlet (Igluligaarjuk). Most of the party suffered from snow blindness, and Beads froze two of the toes on his right foot. Food became scarce and (according to Beads’ family lore), had it not been for Beads and his Inuit guide discovering an Inuit camp, the possibility existed that the entire party might have starved. Although it took some effort on Beads’ part and that of his guide to convince the Inuit of their objectives, they succeeded in the end and not only managed to obtain sufficient food but also information regarding the Franklin party. (McGoogan, in his book, tells a somewhat different story in which Rae plays a larger role and Beads a much more minor role). For the remainder of the winter, the party lived within the Inuit community and, in the spring returned to Winnipeg. Dr. Rae then returned to England, taking with him the information which they had collected.

Jacob Beads continued to live in Manitoba for a number of years, marrying at the age of 30. He and his wife moved to Fort Ellis (near the present day Qu”Appelle) where their four children were born. Eventually the family moved to Prince Albert in 1873, and down river to The Forks in 1880. In addition to continuing to run a grist mill at The Forks, Beads began building river boats for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

An extract from Saskatchewan History, Volume VII, Number 1, Winter 1954 indicated “Mr. Beads was one of the last, if not the sole survivor of Dr. Rea’s (spelling incorrect) Franklin search expedition and survived his commander by a few months”. The extract goes on to say that Beads “also had the honor of bringing the first grist mill into the district”.

The extract would appear to have been a quotation from the April 6th, 1894 edition of the Saskatchewan Times which carried a story regarding Beads’ death after he passed away peacefully at his residence at the Saskatchewan Forks at the age of 68 years. Again, the article referred to him being one of the last, if not the sole, survivor of the Franklin expedition, surviving his “commander, in terms of whom he spoke in terms of high respect. The story also referred to Beads’ operation of the grist mill which, for many years, did “good service for the earliest settlers under his management”.

Beads was described as “remarkable for his kindly disposition” and a man who “preserved in the highest degree that cordial hospitality so characteristic of the old native stock”.

It was noted that while in the employ of the Hudson’s Bay Company, or earlier with his father who was also an HBC employee, Beads travelled extensively throughout the Northwest Territories, but most especially through that portion of the Territories which were mostly unexplored regions. Beads was noted as being especially gifted with keen observation and a retentive memory, which resulted in his ability to reminisce in later years, providing great enjoyment for those with whom he associated.

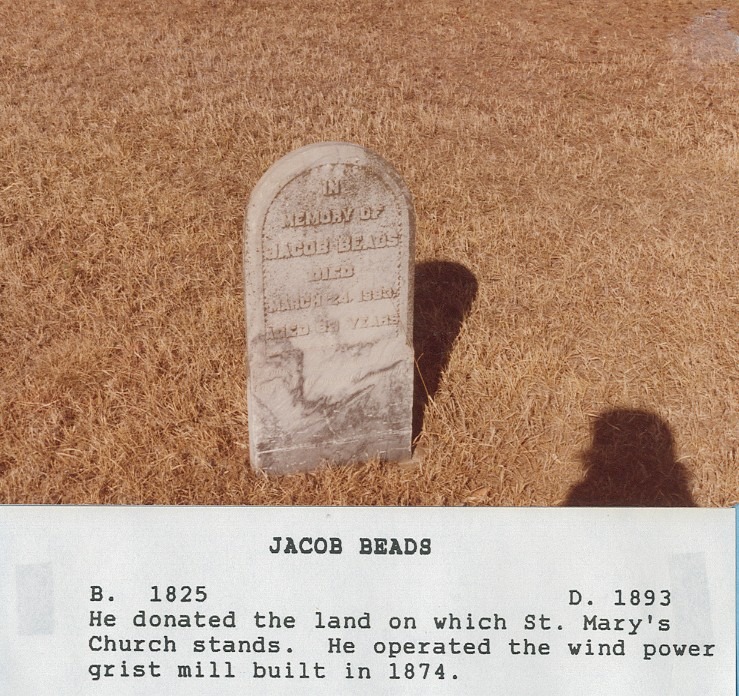

As a member of the Church of England (now the Anglican Church of Canada) and holding a high personal regard for John McLean, the first bishop of the Diocese of Saskatchewan, Beads made a handsome present in 1875 of a large portion of ground on which the original University of Saskatchewan (Emmanuel College) was built, and on which St. Mary’s church was constructed and was surrounded by its cemetery. The story of his passing concluded with the happy thought that Beads should be interred in the consecrated ground which had once “been his own domain”.

Jacob Beads’ actual date of death remains in dispute. The Saskatchewan Times article suggests that Beads was interred on March 28th, 1894. However, the letters of administration issued to his daughter in 1913 indicate that his death date was March 24th, 1893. Beads’ daughter, in an interview with the Prince Albert Daily Herald in 1951, also reported that her father had died in 1893. Records from the Anglican Diocese of Saskatchewan indicate that the date of death was March 24th, 1894 and the interment date was March 28th, 1894.

Regardless of the foregoing confusion regarding the date of Beads’ death, the fact remains that two persons who were so involved in the exploration of the Arctic are buried in a small, parochial cemetery near the City of Prince Albert.

fgpayton@sasktel.net