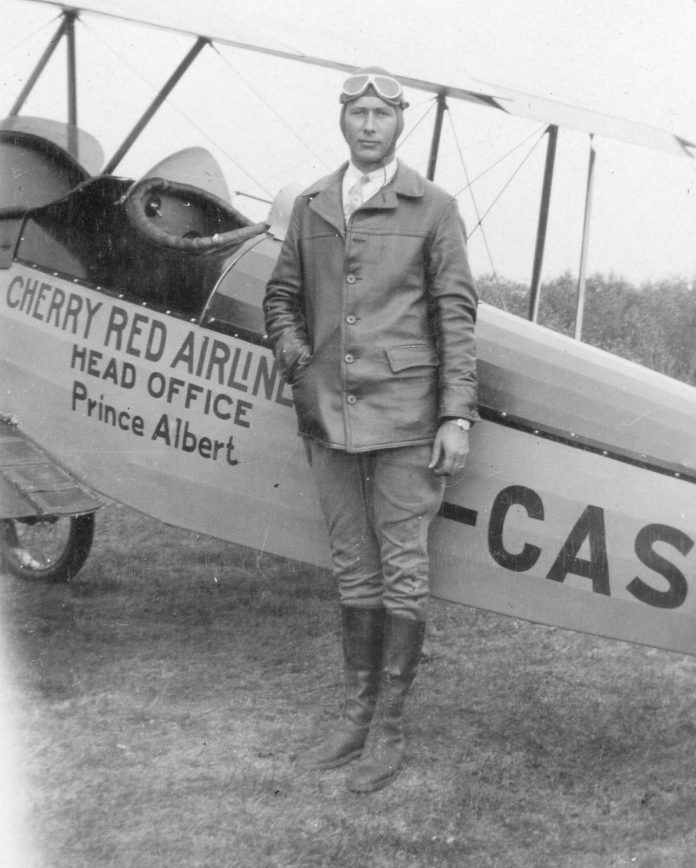

Harry Holroyde, the secretary of the Bradshaw-Holroyde Agencies Limited, was a Prince Albert entrepreneur in the first part of the 20th century. In 1929, Holroyde lived in the Bank of Ottawa building on 1st Avenue West, the same building which housed the Bradshaw-Holroyde Agency. He was, at that time, the president of a short-lived aircraft company, Cherry Red Airlines. The airline’s story is not only interesting, but had a major role in the early history of aviation in northern Saskatchewan.

On a warm day in May in 1928, a young man named Norman Cherry flew into Prince Albert in an old Pheasant airplane piloted by Alva Malone. They landed in a field between Saskatchewan Penitentiary and St. Mary’s cemetery.

A single-engine, two-seater biplane, it had originally been built in Memphis, Missouri, in 1927. Cherry had paid $2,800 (approximately $50,000 in today’s money) for the aircraft, but after excise duty he had expended $3, 733 (approximately $60,000 today). Fabric-covered, with wire spoke wheels, the biplane had a wing span of ten metres. The V-block engine was glycol cooled, and able to travel at a cruising speed of 135 kilometres per hour. According to a newspaper report of the day, it had taken them fifteen hours flying time to travel from Memphis to Prince Albert.

Norman Cherry had been raised on a farm at Debden. In 1921, he relocated to Chicago, Illinois, where he ran a garage during the winter. In 1923, he moved to Florida where he worked in the construction industry. Eventually he sold his interest in the Debden farm and settled in Culver City, California, building sets at movie studios. Given the interest in airplanes being shown throughout North America and Europe, Hollywood was producing numerous movies about flying, and the city of Los Angeles was quickly becoming an aviation centre. The transplanted Canadian was just as fascinated as so many others.

His return to Prince Albert and area was supposed to be simply to visit his parents and renew acquaintances with old friends. But Cherry and Malone found that there was money to be made by barnstorming the province’s summer fairs and offering rides to adventurous citizens.

Other opportunities presented themselves as a result of newly discovered minerals in the area between Lac la Ronge and Rottenstone Lake. Prospectors heading into the area were looking for any possible means of transportation available. Cherry was willing to provide that transportation, but his Pheasant was a wheeled aircraft and landing strips were few and far between in northern Saskatchewan. Furthermore, the Pheasant was really a single passenger plane, although it could manage two persons if necessary. And furthermore, it had a limited fuel capacity, which allowed it to fly as far as Lac la Ronge and back to Prince Albert, meaning that passengers and supplies could only be transported halfway to Rottenstone Lake.

This is where Holroyde came into the picture. Not only was he a businessman, but he had flown in the First World War. Cherry felt that there could not be a better individual to start an airline company. Holroyde agreed, and the Cherry Red Airline Limited became a reality.

It was apparent that an airline would need an airplane, and so Cherry was sent to Cincinnati where the partners had a line on a plane called the International. Unfortunately, when Cherry arrived in the Ohio city, he found that the company had gone bankrupt. When Holroyde was notified, he sent Cherry a telegram encouraging him to go to New York where a big airplane show was about to start at the Grand Central Palace. All of the movers and shakers in the aviation industry were gathered there including Fokker, Chamberlain, Levine, Courtney, Amelia Earhart, Frank Hawkes, and many others. Cherry, Malone, and Holroyde would meet there and determine their next move.

By the end of the show, Cherry Red Airlines had purchased a Buhl Cabin Aeroplane. This was a plane which was powered by the first Wright 300 horsepower engine ever in service. It could cruise at 185 miles per hour. Prior to that, the most powerful engine in service had been 200 horsepower, which was the engine Lindberg had in the Sprit of St. Louis when he made the first solo trip across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Buhl was a six-seat biplane, with an upper wing span of 40 feet (12 metres) and a lower span of 25 feet (eight meters). Each wing had a 60 U.S. gallon (230 litres) fuel tank. The cockpit had large windows, and included a periscope which allowed the pilot to look back over and beyond the top of the plane. It was also a comfortable aircraft, with upholstered seats, flush-mounted dome lights, heaters, window shades, and ash trays.

The company’s new plane was flown from Mineola Field to Maryville, Michigan, where it had to clear customs. The necessary red tape which had to be navigated took nearly three weeks, time which was costly for Cherry Red Airlines. Back in Saskatchewan, Consolidated Smelting had taken an option on the Rottenstone property, and had begun drilling. Consolidated Smelting was paying $700 per trip into their property, and up to two trips per day were being flown. Another airline, Western Canadian, sent in a plane flown by H. Hollick-Kenyon, and they secured the business.

The Cherry Red plane finally passed customs, and Holroyde, Cherry, and Malone were once again on their way home. But yet another delay occurred. Flying from Winnipeg to Prince Albert, Malone was concerned that his fuel might not hold out. As a result, he touched down in Kelvington to top up the tank. When he took off, the plane struck a rock which was hidden underneath the snow, damaging part of the undercarriage.

When the plane finally arrived in Prince Albert in the latter part of March 1929, the company was finally able to get in a few days of profitable flying prior to the river ice melting. Consolidated Smelting had determined that they would organise their own flying service, but before they managed to do so, Cherry Red got some of the spring business, having put floats on the plane so that they could land on water. This spring business entailed flying hay into the smelting company’s camp to feed the horse utilised to haul their diamond drill around. When the ice went out, they were unable to feed the horse, which led to the contract fly in hay. For each bale, Cherry Red charged $50 per bale. When Consolidated Smelting’s head office received the Cherry Red account bill from their local manager, the decision was made to shoot the horse.

Later that year, when Malone was flying the Reverend G.N. Fisher, his wife and two children from Christopher Lake to Lac la Ronge, he had engine trouble (the main bearing having burnt out) and found it necessary to land on a small lake, which the local newspaper actually called a slough, about 30 miles south of their destination. It was due to the pilot’s expertise that no one was hurt during the landing, but the Fisher family chose to not fly again.

With the Rottenstone service failing to live up to expectation, and other aviation business being somewhat limited at that time, due to the New York stock market crash only days after the crash of the Cherry Red plane. This led to a sudden end to all the mineral prospecting in the north, and the failure of many of the companies which were indebted to the airline. The decision was made to wind up the company, with shareholders receiving 65 cents on the dollar. When the company was dissolved in 1931, although not a business success, the company was the first and only aviation firm to fly in northern Saskatchewan which had been funded by neither the federal government or big business.

Cherry Red also pioneered air mail in Canada. In order to increase their revenue, they established a service allowing customers to have their mail transported on the Cherry Red flights. The company issued 25,000 of their own air mail stamps. A ten cent Cherry Red stamp was required for each ounce of correspondence.

The Canadian Postal Service had not yet issued air mail stamps and as a result would keep Cherry Red’s stamps on hand, and anyone living in the north could instruct the Postal authorities to give Cherry Red the mail and have it flown to or from Prince Albert at the stated rate. Cherry Red stamps are very rare, and sell today for a considerable price amongst stamp collectors.

There are so many interesting Prince Albert stories. I encourage everyone to take time this summer to visit the four museums managed by the Prince Albert Historical Society. Those of you who have children or grandchildren, nieces or nephews will also want to check out the summer camps being held at the Historical Museum. More information can be found on our website and Facebook page, or at the Historical Museum.

fgpayton@sasktel.net