In the image

A friend phoned after reading one of my columns. They referred to my calling my relationship with an ex-offender friend a significant part of my spirituality. There was wondering about what that might mean.

I’m not at all sure that I answered my caller to my satisfaction and so it invited further rumination about what I might have said. Mostly, though, it reminded me of a story. Most things do.

Decades ago I attended a church related event. Someone was leading a conversation about spirituality. Of course, their opening query was to ask for definitions of that word, “spirituality.”

Obviously, it was a hard question. No one responded. So I did. “Spirituality is the search for that which makes being alive good.” I was a little proud of myself, this was a personal definition that I had been tweeking most of my life. It didn’t particularly suit the purposes of the person leading the conversation. I sensed that something more ecclesial was sought, something that circled around the word God. Dictionaries support that direction.

Though that was two plus decades ago, that same definition continues to wander ahead of me, leading my ruminations and ponderings. “Spirituality is the search for that which makes being alive good.”

A rejoinder from the person leading that long ago discussion was, “Well, food makes being alive good. Is that spiritual?” I hoped that the conversation might go there, because, yes, food is definitely part of my spirituality, and of yours, I suggest. But no, it was, I suspect, spoken to highlight the insufficiency of my response.

On Sunday, I attended a church service. Time in church is, for me, closely connected to searching out what makes being alive good. The day before, I spent time with my son and grandson rebuilding a truck engine, an engine that will eventually power said grandson’s old Ford pick up. Certainly, that day was integral to my spirituality. Three generations working together on a family mechanical project, with the fourth generation, my father, very much there in spirit, this points squarely at that which makes being alive good.

Last week, I messaged another grandchild, asking how the week was going. The quick response was personal and powerful and delightful. Certainly it made being alive good.

Tomorrow, Monday, we will join the gang in the local hall for senior’s coffee time. Fifteen or twenty people will share stories of their week, or of their past, stories that run the gamut of emotions from anger to joy. Often, huge trust is held out across the table, a precious gift. Again, this becomes a significant marker in making my own life good.

On it goes, through the days and weeks and months of what is now astoundingly 2024. Spirituality is, in my experience, so much bigger than a Sunday morning sermon. To use God language alone to define the word, “spirituality,” is to blinder it, to deliberately block it away from the hugely significant events of daily life.

How might our spirituality serve us if we could, every morning as we lever our bodies from our beds, if we could identify, perhaps only slightly, a sense of anticipation? Where might our spirituality take us, if we nurtured, encouraged our curiosity to lead us to those places where we are reminded of what makes being alive good?

I acknowledge that as an introvert, this has taken some effort. There was a time, still is on occasion, when the world seemed too threatening, too fast, too sophisticated, too wrong. Those were times that I was not so spiritually healthy. Those were times when it was so much easier to remain sequestered and judgemental. Those were the times that were dark.

I have surrounded myself with good people, good supports. I have paid work and volunteer work and hobbies that fill my life with good things. I have modelled to me often that healthy spirituality is connected to honesty, vulnerability, humility. It embraces laughter and tears, in fact healthy spirituality blesses all of the emotions that reside within us and demand expression.

If musings in these direction entertain or amuse you, feel free to develop your own definition of spirituality. Give words to whatever moves you forward, whatever challenges to you experience beauty in every experience, every day.

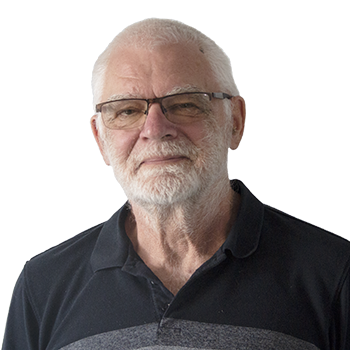

Ed Olfert is a retired clergy person who continues to find glimpses of holiness in every step. These days, his steps wander further into the world.