by Joan Champ

This is the second in a series of columns about the 70 British Home Children sent to St. Patrick’s Catholic Orphanage in Prince Albert between 1901 and 1907. While all orphanage records were destroyed in the terrible fire of 1947, every attempt has been made to trace the life stories of these dispossessed children through genealogy websites and newspaper databases.

The Daly Siblings: Part One – Arrival

Among the weary group of four boys and four girls who were met at the Prince Albert railway station by George Russel’s democrat on October 7, 1901 were the Daly siblings, Daniel (11), Joseph (10), Evelyn (8) and Violet (7). They had boarded the steamship Tunisian at Liverpool, England with their father, Daniel Daly, Sr. on September 19th. Their destination was the newly founded St. Patrick’s Catholic Orphanage in Prince Albert.

It was unusual, but not unheard of, for a parent to accompany the little ones who became known as British Home Children to their new homes overseas. The majority, however, of the 80,000 impoverished children sent to Canada from England between 1867 and 1917 had been separated from their parents by so-called child rescue societies. This included the Catholic Emigration Society that sponsored the Daly children’s shipment to Canada in 1901.

Typically, struggling British parents – especially single mothers or those with large families – would agree to their children being “taken into care” by rescue homes on a temporary basis, but few consented to their offspring to be sent to Canada permanently. The children – usually between the ages of 3 and 14 – were almost always sent abroad without their parent’s knowledge. However, not only did Daniel Daly consent to the emigration of his four youngest children, but he also went along to get them settled in the remote Canadian orphanage.

Irish-born Daniel Henry Daly (1853-1907), a shoemaker by trade. He joined the British Army in 1880, marrying Esther Gittens in 1883. Daniel’s army medical records reveal a checkered career, with time spent in jail for drunkenness. He served in Egypt with Kitchener from 1884 to 1886, retired from the army in 1900. A disabled veteran, he moved with his wife and five children to London on a meagre pension payable every three months.

In 1901, Esther Daly (1853-1926) fell ill and had to be hospitalized for several weeks. Without her knowledge, her husband took their four youngest children to Canada and placed them in Prince Albert’s Catholic orphanage. (Two older daughters, Ellen and Mary Victoria, remained in England.) According to a Daly family descendant, Daniel reportedly said that he had two choices: “he could send his children to the workhouse or he could send them to Canada.”

Before coming to Canada, many of the British Home Children had spent time in workhouses – institutions designed to provide shelter and mandatory work for people who were struggling to support themselves and their families. There were thousands of workhouses across the United Kingdom in the late 1800s sheltering tens of thousands of the poor and destitute. Conditions were harsh. Families were divided, with children separated from their parents and siblings into children’s homes, some for boys and some for girls. As the costs of running the workhouses and children’s homes escalated, child emigration appeared to offer a cheap and effective alternative. For example, on 1 January 1907 there were 60,421 institutionalized in the United Kingdom, not including reformatories and industrial schools. As council rates went up every year to cover the cost of these children, its easy to see why emigration at £10-£12 per child was so attractive. [Sarah Francis, British Home Children Advisory & Research Association, Facebook.]

From the British perspective at the time, Canada was seen as an ideal destination for endangered poor children. Sparsely populated, Canada retained what Roy Parker calls the “virtues of a rural existence, uncorrupted by the immorality and other depravations associated with urban industrial life.” [Uprooted, 2010] Even better, there was ample agricultural land which could enable immigrant children (especially boys) to establish themselves on family farms. This theory was to prove true for the Daly boys.

After dropping his two sons and two daughters off at St. Patrick’s, Daniel Daly rarely saw them again. He found work with the Hudson’s Bay Company, manning freight wagons to Big River, Green Lake, and Ile a la Crosse. He later worked as medic and cook on boats plying the waters of Lake Athabasca. His last job was at the Driard Hotel in Wetaskiwn, Alberta where he worked as a porter; he died there at age 60 in 1907.

Esther Daly, mother of the four children, briefly reunited with her son Joseph when he went overseas during the First World War. She died in the Dover workhouse on 19 March 1926.

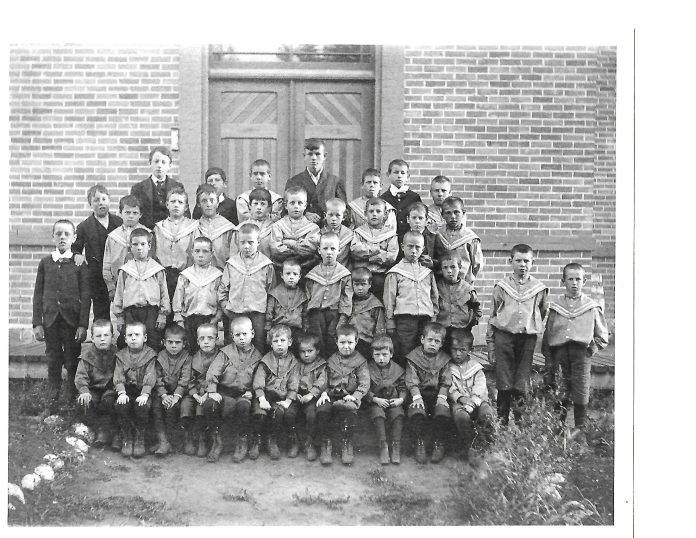

The four Daly children spent their school years at St. Patrick’s. Daniel’s great granddaughter told me that, “though I never met him, I was told that he didn’t have a good experience in the orphanage.” In Part Two of the Daly’s story, I will discuss conditions at the institution in the early days and follow the children into adulthood.