Mistletoe has been used by many ancient cultures, and although the leaves and berries of some species are toxic the plant has also been used historically for curing a number of ailments, including arthritis and infertility. It was also associated with peace and love by the Romans, who hung it over doorways to protect the household.

It has become a part of Christmas celebrations worldwide since the 18th century, and nowadays couples are expected to kiss when standing under a bunch of mistletoe. This tradition has been popularized by the music of the 50’s – “I saw Mommy kissing Santa Claus, underneath the mistletoe last night….”, and by more recent songs. The tradition of kissing under the mistletoe became very popular with the servants in Victorian times. Apparently any man could kiss a woman who was standing under the mistletoe, and if she refused him she would suffer from bad luck. At one time a berry was removed for every kiss, until the branch was bare – and presumably the kissing stopped. This tradition is no longer popular, probably because bunches of mistletoe are usually quite small and expensive in countries where the European mistletoe does not grow, and often artificial plants are used, making the berries non-expendable.

Mistletoes are hemiparasitic plants that feed on other plants, so they do not need roots to grow in the soil, or green leaves that can photosynthesize. They produce specialized structures called haustoria that penetrate the host plants’ tissues to extract the water and nutrients necessary for their growth. However, they do have leaves capable of photosynthesis for part of their life cycle. A commonly known species of mistletoe, the European mistletoe (Viscum album), is native to Britain and much of Europe, and it is the mistletoe plant used in Christmas decorations. It is very noticeable in British apple orchards, particularly in wintertime, when the trees are leafless. The mistletoe consists of woody stems that bear smooth-edged, oval, yellowish evergreen leaves and waxy, white berries that are present on the branches in clusters of 2-6. Mistletoe berries contain seeds that are coated with a sticky jelly called viscin, and for many species the seeds are spread by birds. Different kinds of birds spread the berries of different species, and they may use different methods. The seeds may be ingested, then regurgitated from the crop. Seeds of other mistletoe species may pass through the digestive tract and are then dispersed in the bird droppings. The seeds may also stick to the bill of a feeding bird, and are then wiped off onto the bark of a different tree. When the seed germinates on the branch of a suitable host, it produces a hypocotyl (the stem of a germinating seedling) that grows towards the bark of the tree, and eventually penetrates the bark. This can take a year or more, and until the haustorium is formed inside the host and reaches the conductive tissue, the mistletoe has to rely on its own photosynthesis to survive and grow.

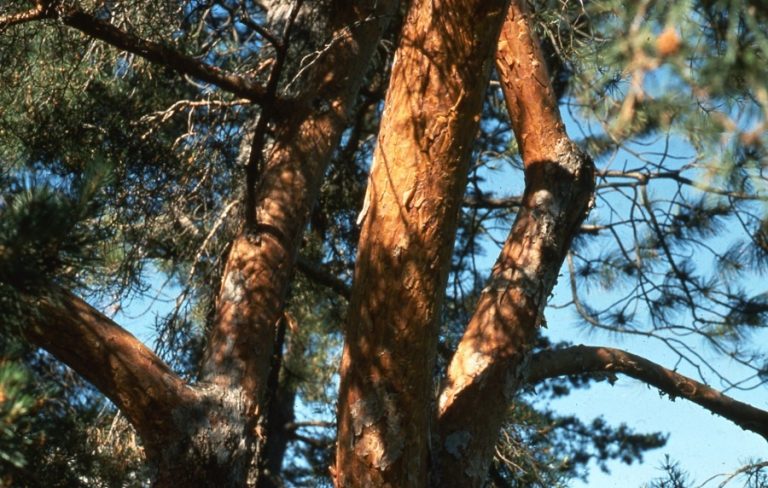

Other species of parasitic plants that grow in a similar fashion are also called mistletoe, and they are found in many parts of the world, including South America and Australia. There is even a species of mistletoe that occurs in Saskatchewan. Dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium pusillum) is parasitic on white spruce and other conifers. It has a fragile stem, and small, scale-like leaves. There are male and female flowers, found on separate plants, and although the mistletoe plant itself is inconspicuous it causes the host tree to form many branches around the infected area. These bushy growths are called “witches’ broom” and are very noticeable. I recall collecting specimens from infected coniferous trees south of Meadow Lake for plant pathology classes in the 1980’s, and they were easy to spot. Dwarf mistletoe is not a species that could be used as a Christmas decoration! It is now rare in the province and is only found in eastern Saskatchewan.

Very best wishes for a happy holiday season, I hope you have many festive plants to enjoy.

Jill Thomson is a plant disease specialist (retired) who enjoys gardening in Saskatoon with her family, including the dogs. This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events

The Holly and The Ivy ….and The Mistletoes

Poppies, Poppies everywhere

Ginnie Hartley

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

Almost everyone recognizes the red poppy that many people wear on their lapels on Remembrance Day. And many people know that Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, who was a Canadian Medical Officer during the First World War, wrote the poem ‘In Flanders Fields’, which speaks of the poppies that bloomed there. However, records indicate that the significance of the poppy can be traced back to the Napoleonic Wars in the early 19th Century, over 110 years before being adopted in Canada. Records from that time indicate how thickly poppies grew over the graves of soldiers in Flanders, France during those wars. These poppies are of the species Papaver rhoeas, the red-flowered corn poppy, which often thrives in areas of disturbed soil.

John McCrae’s poem inspired Madame Anna Guerin of France to found a charity which created poppies made of fabric, to raise funds to help rebuild regions of France torn apart by the First World War. She presented her idea of using the poppy as a symbol of remembrance for fallen soldiers to the Great War Veterans’ Association, the precursor to The Royal Canadian Legion, and it was adopted in 1921.

Some people choose to wear white poppies as an alternative to the red poppy. It symbolises remembrance of all casualties of war, including civilian casualties. But white poppies have been criticised for detracting from the meaning and the funds of the red poppy. Animal Aid in Britain issues a purple poppy as a reminder that both humans and animals are victims of war. In 2018, another unique commemorative poppy, the Khadi poppy, was commissioned by the Royal British Legion to mark the Centenary of the end of the First World War. The red cloth poppy is identical to the usual Remembrance Day poppy, but it is made out of the traditional handwoven Gandhian cloth (Khadi) and honors the British Indian soldiers who fought in the World Wars.

In 2014 a sea of 888,246 ceramic red poppies were used to form a weeping wall of red at the Tower of London, UK. This art installation was made to mark the 100 years since the start of World War One, and for four years it was moved and installed on other cathedrals in Britain.

Of course, poppies have uses other than for remembrance of the fallen. Their beautiful colors (not only red) make them a popular addition to flower beds. Growing them can be as simple as planting seeds in average, or even poor soil in a sunny location. Roots can also be divided, and this should be done in the fall.

Ancient Egyptian doctors would give poppy seeds to their patients to relieve pain. The Minoan civilization (~2700 – 1450 BC) grew poppies for their seeds and used a milk, opium and honey mixture to calm crying babies. The seeds contain small quantities of both morphine and codeine. Seeds that are harvested about twenty days after the flower has opened are non-narcotic because then the morphine is no longer present. Seed capsules of the opium poppy can be processed chemically to produce heroin for medicinal use and for the illegal drug trade.

Poppy seeds are also a rich source of thiamin, folate and several essential minerals including calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus and zinc. They are often used as a spice and decoration for baked goods. The seeds can also be ground and used as a filling for pastries. They also produce an oil which has no odor and a pleasant taste, and is less likely than other oils to become rancid. The oil can be used for cooking, and also as a skin moisturizer.

The petals contain a red dye which is used in some medicines and wines. The dried petals are occasionally used to give color to potpourri.

So when you pin on your Remembrance Day poppy, remember that it is not only a symbol of memory, sleep and death, but also is ubiquitous in the flower bed, the pharmacy and the kitchen.Ginnie Hartley is a retired Speech-Language Pathologist who loves gardening almost as much as she loves words. This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events.

Pumpkin Celebration

Jill Thomson

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

In Saskatchewan, October could well be known as the month of the pumpkin, because of the 2 celebrations that both use pumpkins. In early October, on the Thanksgiving holiday, many families celebrate by eating a special meal together, and pumpkin pie is often a favourite dessert. On October 31, we celebrate Halloween, and pumpkins are on display, carved so that a light can be inserted into the hollow pumpkin, to illuminate the carved design.

Many grocery stores have large bins of pumpkins for sale, some of which are now supplied by local growers. There are also “pumpkin patches” where you can select and buy pumpkins that are either pre-picked, or you can go out into the field to select your own. I visited a patch a few weeks ago and it was a very happy place, with small children, and adults, enjoying being able to choose ”their own” pumpkin.

It is not difficult to grow your own pumpkins as long as there is room in your garden for a plant that likes to ramble, climbing any obstacles in its path. The seed can be sown directly into the soil once the soil temperature is at least 15°C. However, the plants do need at least 110 days to grow to maturity and it is better to start seeds indoors not more than 3 weeks before the danger of frost has passed. The young plants can then be transplanted. It is important to remember, however, that vine crops do not like to be transplanted so disturb the pumpkins roots as little as possible when transplanting. Pumpkins like a fertile soil, so well-rotted compost or manure should be incorporated before planting, and plants should be watered well during the growing season. They also like a sunny location, and we plant ours beside a corn row, as they will grow through or along the row. They will also climb up a frame, or wire, but then you need to provide a sling, or other support, for the developing fruit.

Pumpkins can grow very large, and heavy, depending on the variety you choose. Some gardeners like to grow huge varieties, with competitions to see whose is the largest. The world record weight in 2021 was 1226.1kg. That would make a lot of pies! Some people have grown them big enough to act as boats when they are hollowed out, and in 2021 a man from Nebraska paddled 38 miles down the Missouri, in a 384 kg pumpkin, to challenge the previous record of 25.5 miles.

Typically, we grow mid-sized pumpkins that are large enough to be carved at Halloween, but can still be carried by a strong adult. This year our ‘Big Moon’ plants produced big pumpkins suitable for carving, and ‘Spirit’ hybrid cultivar was good for pies. We do also cook the flesh of the carved pumpkins to feed to our dogs: this is an excellent addition to their diet and helps bulk-up a meal for any dog on a diet.

The tradition of carving pumpkins is connected to the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, which marked the end of summer and beginning of the New Year in ancient Britain and Ireland. On that day the souls of those who had died would pass to the Otherworld, and other souls might return to visit their homes. In Ireland, people began to carve turnips into frightening faces, to scare away a particularly bothersome soul called Stingy Jack. The Irish folk who immigrated to the USA began to carve faces into pumpkins, which were readily available, unlike turnips. As the trend is now to make Halloween less frightening, and more a fun time for children, the carvings are not intended to be scary but are rather a display of the skill of the carver!

Pumpkin plants are native to North America, and have been farmed by indigenous people for over 9,000 years. Pumpkins ripen in the fall and were used for feasts at that time. Early recipes mention roasting a hollowed pumpkin filled with milk, spices and honey, over an open fire. Native Americans gave settlers gifts of pumpkins and demonstrated how to cook them. It is likely that cooking pies using a sweet pumpkin filling would have been developed by settlers preparing Thanksgiving meals. There are many variations on the pie, my favourite is a pumpkin cheesecake. It has been estimated that about 50 million pumpkin pies are consumed for Thanksgiving every year in the USA.

Enjoy pumpkins this month; admire their glowing orange colours, the scrumptious desserts produced for Thanksgiving, and the elaborate carvings on display at Halloween.

Jill Thomson is a plant disease specialist (retired) who enjoys gardening with her family in Saskatoon. This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check out our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial).

Brussels Sprouts – a superfood

Jackie Bantle

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

As cooler temperatures bring us indoors and in closer contact with other humans at the start of flu season, many of us are looking for superfoods to boost our immune systems. You may be familiar with the antioxidants found in blueberries, haskap and cranberries but were you aware of the cancer-fighting glucosinolates and immunity boosting Vitamin C in Brussels sprouts? Brussels sprouts are considered a cold-weather super food.

Believed to be a descendent of Mediterranean kale, Brussels sprouts have a been popular vegetable for centuries, first gaining significant popularity in 13th century Belgium. Like other members of the Brassica family (which include cabbage, broccoli and cauliflower), Brussels sprouts prefer growing temperatures around 20-25˚C for optimal growth. However, unlike other brassica vegetables, Brussels sprouts require a long season to mature and must be transplanted in spring.

Young Brussels sprout transplants look like any other cabbage, cauliflower or broccoli plant however, during the season, Brussels sprouts grow into 50-100cm tall stalks (depending on the cultivar). Each stalk may produce 15-20 or more sprouts.

Brussels sprouts transplants should be started indoors, in spring, 6-8 weeks prior to transplanting out. Seeds will germinate in 5 or 6 days after planting. Supplemental light will be necessary to produce healthy, sturdy transplants. Brassica transplants can be transplanted outdoors as soon as daytime temperatures reach 15°C and night temperatures are above 0°C. Harden off transplants prior to planting out by moving them outdoors into a sheltered, frost-free location at least 3 days prior to transplanting. Young brassica transplants that have been hardened off can withstand a few degrees of frost.

Brussels sprouts prefer full sun, rich healthy soil and about 2.5cm of water/week during the growing season. By mid-season, there should be some sign of tiny sprouts forming in the leaf axils along the stem. In order to get the modified leafy buds (sprouts) along the main stem to develop and enlarge, the growing point of each plant should be removed during the 3rd week in August. Simply break off the top 1cm of the plant. Instead of continuing to add growth on the top, the plant will put its energy into developing the sprouts along the side of the stem. By early October, the sprouts should be a good size for harvest. For best flavour, harvest Brussels sprouts after a fall frost (or two) of -3°C. The cold temperatures sweeten the sprouts. Brussels sprouts can withstand several hard frosts of -4/-5ºC as long as day time temperatures allow plants to thaw during the day. Sprouts should be harvested when they are bright green and before they turn yellow.

Harvest Brussels sprouts by removing the side leaves and cutting the stalks off just above the soil. Remove any diseased or yellowing sprout leaves. Store stalks and sprouts in plastic bags in the fridge for up to one week or remove sprouts from stalks and store sprouts in plastic bags in a fridge. Ideal conditions for fresh Brussels sprouts storage is 1ºC and 80% RH.

For long term storage, blanch Brussels sprouts in boiling water for 4 minutes. Remove from boiling water and immediately place in an ice bath. Remove sprouts from the ice bath, pat dry and freeze in sealed plastic bags or containers. Frozen sprouts can be stored for up to ten months.

When cooking after freezing, do not allow sprouts to thaw before cooking. Place frozen sprouts in sauté pan or oven directly from the freezer. Overcooking tends to produce a mushy texture and excessive sulphur flavour. Brussels sprouts are loaded with vitamin C, A, potassium, calcium and fiber. Unlike many vegetables, Brussels sprouts contain protein (100g contains 3.4g of protein).

Growing brassica vegetables like Brussels sprouts in an area where a lot of canola or mustard is grown on a large scale can be a challenge. The large acreages of these two field crops attract a wide variety of Brassica pests and diseases to the Prairies. Flea beetles, cabbage loopers, root maggots and club root are all possible problems with growing Brussels sprouts. Be prepared to use crop covers or contact your local garden center for pest and disease control solutions.

This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check out our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial).

Mum’s the word

Sara Williams

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

Chrysanthemums (Chrysanthemum x morifolium) (also known simply as ‘mums’) bring colour to the autumn border, are great cut flowers and are attractive to butterflies. But they require special attention to overwinter and are not easy perennials to grow in prairie gardens. Cultivated in China for over 2,500 years, they were brought to North America in 1798. The genus name is from the Greek words chrysan and themum, meaning golden flower.

They have a short, fibrous root system which forms a dense, woody crown from which emerge many stems. Flowers may be single and daisy-like but are more commonly double. Varieties developed for northern gardens begin to flower in August, triggered by shortening days

Care

Plant them in full sun in well-drained but evenly moist soil rich in organic matter. A summer mulch helps to maintain even moisture and suppress weeds. Use a balanced fertilizer such as 20-20-20 or organic fertilizers such as alfalfa pellets, blood meal or bone meal to promote vigorous growth. Pinch the plants in early summer to encourage branching and more abundant flowering.

After the first severe killing frost in fall, cover them with 15 to 20 cm (6-8 in.) of organic mulch such as shredded leaves or clean straw to prevent soil heaving and drying due to freeze-thaw cycles and to protect the crowns from winter’s cold. Remove the heavy mulch as soon as spring temperatures rise above freezing and snow recedes. Divide every second year to keep the crowns vigorous and improve their chances of winter survival. Plants can be divided as soon as the soil warms in the spring or from cuttings taken in early spring.

The Chrysanthemum Conundrum

Experienced prairie gardeners report very limited success in overwintering mums in the garden as they seldom survive without significant interventions in zone 2 and 3. It might be easier to simply treat them as annuals.

Hugh Skinner grew and propagated the Morden series of mums for years in his nursery near Roblin, Manitoba. He started plants in the greenhouse in late winter from stock plants overwintered for one year in the garden. These plants had been grown with excellent drainage and shelterbelt protection. With the exception of ‘Morden Garnet,’ which died, the Morden mums generally survived only their first winter outdoors. The following fall, the large clumps would be dug, potted, and stored in a root cellar until brought into growth in the greenhouse to produce cuttings in late winter.

Plants left in the garden generally did not survive a second winter. The “secret,” beyond planting them in a protected, well-drained site, was to divide or start new plants every second year. The experience of a veteran gardener in Saskatoon has paralleled that of Hugh in Manitoba.

Varieties

‘Baby Tears’ – compact plant (30 cm / 12 in. x 40 cm / 15 in.), white pompom flowers tinged pink.

‘Holly’ – golden yellow, pompom flowers on compact plants (40 cm / 15 in.).

‘Prairie Lavender’ – shell pink with yellow centres (60 cm / 24 in.).

• The Firecracker series, from Jeffries Nurseries, breed by Rick Durand, are about 50 cm (20 in.) in height.

‘Dream Weaver’ – soft mauve-pink

‘Firestorm’ – mauve-pink to scarlet-red with yellow centres

‘Power Surge’ – double red

‘Showbiz’ – pink-mauve, pompom

‘Stardust’ – dusty mauve, quill-like petals with yellow centers

‘Suncatcher’ – bright yellow, double

‘Tiger Tail’ – bright orange-yellow

• The Morden Series, Agriculture Canada Morden Research Station, 1960s -1970s are 40 to 50 cm (15-18 in.) in height and spread.

‘Morden Cameo’ – double, creamy white (40 cm / 15 in.).

‘Morden Canary’ – bright yellow (45 cm / 18 in.).

‘Morden Delight’ – double, bronze-red (45 cm / 18 in.).

‘Morden Fiesta’- bright purple, compact (40 cm / 15 in.).

‘Morden Gaiety’ – bright orange (40 cm / 15 in.).

Other Species

Korean chrysanthemums (C. x rubellum hybrids) are reliable and generally easier to grow in northern gardens than those described above. The single flowers surround yellow disc florets.

‘Clara Curtis’ – deep pink, single flowers with yellow centres (60 to 75 cm / 24-30 in.), has survived for many years in Hugh’s Manitoba garden and in Saskatoon gardens with minimal attention.

‘Mary Stoker’ is of similar stature with yellow flowers overlaid with light pink.

C. weyrichii, an alpine species native to Japan and Sakhalin Island, has large, single, white or pink flowers (25 to 40 cm / 10-15 in.). The most available variety, ‘White Bomb’, is being used by Canadian breeders to develop hardy mums in a variety of colours and forms.

Sara Williams is the author and coauthor of many books including Creating the Prairie Xeriscape, Gardening Naturally with Hugh Skinner and, with Bob Bors, the recently published Growing Fruit in Northern Gardens. She continues to give workshops on a wide range of gardening topics throughout the prairies. This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events

Water Wisely: Saving Water [Part II]

Much of the water directed towards plants never reaches them. It is lost to evaporation, runoff or “non-target areas” such as driveways or patios. Evaporation losses are affected by temperature, relative humidity, wind, droplet size and water pressure. We can’t control temperature but wind can be decreased by shelterbelts, trees and shrubs and fencing.

Design: In conventional landscape design, we consider height, colour, texture and season of bloom, but seldom think of the water needs of plants. We often combine plants regardless of their drought tolerance and then water the entire bed to satisfy the needs of those plants that require the most water.

When designing or redesigning your landscape, group plants in “zones” according to their water needs: those with low water needs (such as yucca, lilac, shrub roses), moderate water needs (cranesbill geranium, basswood/linden, dogwood) and high water needs (birch, delphinium, hosta). Once their water needs are considered, arrange them according to design factors such as height, colour and season of bloom. Grouping plants into beds or borders based on their water needs and then watering them accordingly, makes irrigation more efficient. With an automated system, each landscape zone is scheduled as a single unit.

Mulching: A 10-cm (four-in.) layer of organic mulch (e.g. leaves, shredded post peelings, flax shives) spread on the soil surface between plants, conserves water and greatly reduces weeds. It also prevents water splash onto foliage, thus reducing soil borne diseases such as botrytis.

Bowl-shaped depressions: Forming bowl-shaped depressions with mini “dykes” around newly planted trees and shrubs directs water towards the plants’ roots rather than onto adjacent soil.

Timing: Evaporation losses can be reduced by irrigating when it is calm and cool, usually in the early morning. Plants dry quickly once the sun rises, reducing the risk of foliage diseases such as powdery mildew (which proliferate rapidly under humid conditions). It is also a nonpeak time for domestic water use, so municipal water facilities are less likely to be overtaxed.

Angles: A spray directed at a higher angle covers a greater area, but considerably more water is lost to evaporation and wind drift because the water is in the air longer and wind becomes stronger with increased height. The lower the “angle of trajectory,” the less wind drift and evaporation. Higher pressure usually breaks up the stream of water into smaller droplets which are more easily lost to evaporation and wind drift. The older oscillating type sprinklers are one of the worst for water waste.

Moisture sensors and rain shut-off devices: Rain sensors can over-ride prescheduled irrigation systems so they will not operate when there has been sufficient moisture due to rain. An automatic timer on a hose end sprinkler allows you to water a predetermined amount without fear of forgetting to turn off the tap if you’re away. When a predetermined amount of water accumulates in a collector cup, the system is shut off.

In the fall…

Discontinue watering in late September or early October, when the leaves of deciduous trees have begun to colour and drop. This is your signal that they’re beginning to harden off for winter in response to progressively shorter days and colder temperatures. Continuous watering or the application of fertilizer in late fall may slow the hardening off, leaving trees as well as other plants vulnerable to winterkill.

Once all of the leaves have fallen, give them several deep waterings prior to freeze-up. The objective is to allow them to harden off yet enter winter dormancy with ample water in their tissue and the surrounding soil. This reduces vulnerability to late winter and early spring desiccation.

Retired from the University of Saskatchewan, Sara’s most recent book is Growing Fruit in Northern Gardens with Bob Bors. She’s been hosting garden tours for over 20 years – to Great Britain, Ireland, Europe, Turkey and Iceland. Join her for a tour of French gardens this September [Contact Ruth at 1-888-778-2378, www.worldwideecotours.com] This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events.

Water wisely: Water, Plants and Soil [Part I]

Sara Williams

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

With an average annual precipitation of 30 to 50 cm (12–20 in.), and with about half falling as snow, most plants require some degree of irrigation on the Canadian prairies during the growing season. Our philosophy should be to satisfy the needs of our plants without wasting water.

Understanding the relationship between water, soil and plants helps. Water, whether from rainfall or irrigation, percolates into the soil from the surface, filling the pore spaces between the solid soil particles and forming a “wetting front” that moves downward through the soil.

Different soils absorb and hold water at different rates. The amount of water the soil is able to absorb is called its “water-holding capacity” and is directly related to the organic matter content of the soil and the soil texture. Sandy soils absorb water quickly but have a low water-holding capacity, so lose it quickly as well. The same volume of water moves further and more rapidly in sandy soil. Clay soils absorb water more slowly and are prone to runoff and puddling if water is applied faster than it can be absorbed. The more organic matter, such as compost, that is added to the soil, the greater its water-holding capacity.

Plants themselves require the same amount of water whether grown in a clay or sandy soil. But plants grown in a sandy soil will have to be watered more frequently to obtain the same volume of water. 2.5 cm (1 in.) of water will penetrate to a depth of about 30 cm (12 in.) in a sandy soil and to about 15 cm (6 in.) in a clay soil.

By weight, water makes up 80 to 90 percent of herbaceous annual and perennial plants and about 50 percent of trees and shrubs. Photosynthesis and nutrient transport depend on water. Soil nutrients are brought to the root, enter the root and are carried through the plant in water. It is the internal water pressure that causes cell walls to stretch and cells to grow. As each of the many thousand cells forming a plant enlarges slightly, we see the overall effect as plant growth. As plants increase in size and their root systems penetrate deeper into the soil, irrigation should be less frequent but for longer periods of time, so the water will reach the deeper roots.

How to water

Ideally, water should be applied to the soil, where it can be absorbed by plant roots, rather than to the foliage. When watering established plants, water deeply and thoroughly, to the depth of their root system and beyond to encourage deeper rooting. Roots will only grow where soil is moist. Frequent shallow watering confines roots to the upper level of the soil, leaving plants with a shallow root system prone to drying out between waterings. Greater root growth allows greater water uptake.

Be aware of competition from aggressive plants with extensive, fibrous root systems. The shallow, far-reaching roots of poplar, Manitoba maple, Siberian elm and spruce can rob moisture intended for a nearby lawn, vegetable garden or flower bed.

Remember the trees

Watering your lawn does not mean you have watered the trees in it. Newly planted trees and shrubs need regular watering from planting time to establishment – usually two or three growing seasons. Water (or check the soil to see if water is needed) twice a week during their first month and once a week for the remainder of that season. Through their second and third seasons, water deeply twice a month or as needed. Water mature trees at their “drip line” rather than at their trunk. This is the soil area below the furthest extent of the tree’s branches. Feeder roots – those which absorb water and nutrients – usually end just beyond the drip line and are within the upper 40 cm (16 in.) of soil. Set a soaker hose under the drip line and leave it on until the soil is moist to that depth.

Retired from the University of Saskatchewan, Sara’s most recent book is Growing Fruit in Northern Gardens with Bob Bors. She’s been hosting garden tours for over 20 years – to Great Britain, Ireland, Europe, Turkey and Iceland. Join her for a tour of French gardens this September [Contact Ruth at 1-888-778-2378, www.worldwideecotours.com]

This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events

The rhubarb patch

When I was young, I was convinced that rhubarb grew wild on the Prairies. Every farm that I visited and every abandoned farmyard that I drove past seemed to have a giant rhubarb plant in it. Rhubarb, however, was introduced to the Prairies by early settlers and originally entered North America via Maine and Massachusetts. Its origins are in parts of China (Chinese Rhubarb) and Russia (Russian rhubarb); growing wild in the cold climate of Mongolia, the Himalayas and Siberia. Records show that rhubarb grew on the banks of the Volga river over 3000 years ago. At that time, it was not used in culinary dishes: only the root was used for medicinal purposes. Records from 2700 BC in China indicate that the Chinese rhubarb root (Rheum palmatum) was used extensively as a laxative but also known for curing fevers, preventing the plague, reducing inflammation and healing soldiers. Chinese rhubarb (also known as Turkey or Indian rhubarb) has a much stronger taste and medicinal properties that the rhubarb commonly found in the North American garden (Rheum rhaponticum). The rhubarb that is grown on the Prairies today is a hybrid that was developed in the nineteenth century: the roots have little or no medicinal value.

Rhubarb is one of the few perennial vegetables that survive our harsh Prairie winters. Since it is a perennial vegetable, it is best to plant it along the edge of the vegetable garden where the roots will not be disturbed by tillage or digging. Rhubarb grows best in full sun and rich soil.

Rhubarb seeds will germinate, however, the resulting seedlings can vary greatly in flavour, texture and leafstalk color. it is most efficient to grow rhubarb from disease-free root divisions: dividing roots of a desirable plant ensures that you clone the characteristics that you want. Although rhubarb doesn’t need much care once it is established, it requires a good start. Rhubarb prefers fertile, well-drained soil Dig a hole that is .45m – .6m square. If you are planting a bigger plant or root division, dig the hole to at least twice the size of the plant. Space rhubarb plants at least 1.5m apart. Mature rhubarb plants can be 1-1.75m wide with 2m high flower stalks. The top of the crown should be no more than 5-7 cm below the soil surface. Fill the hole with a mixture of soil and compost (or well rotted manure). Add ½ cup of 10-10-10 fertilizer mixed in with the compost/soil mixture. Pack the soil firmly around the roots and crown being careful not to damage the crown. Fill the hole with the soil/compost/manure/fertilizer mixture until it is level with the surrounding soil. Water in the newly planted rhubarb however, avoid overwatering rhubarb: this will encourage root rot. Spring is the preferred time to plant rhubarb, but planting can occur any time during the growing season.

Later in the season, rhubarb plants may produce flower stalks. On young rhubarb plants, these flower stalks should be cut off near the base. By cutting off flower stalks, the plant will focus all of its extra resources into the roots and leaves rather than using resources to produce seed. Mature rhubarb plants are not negatively affected by seed production.

Rhubarb has few disease or insect problems on the Prairies. Gardeners should be aware of red-leaf disease, however. As the name suggests, red leaf disease is characterized by red or yellow leaves on a rhubarb plant that is losing vigour. The plant will be reduced in size and the crown of the plant may be rotting with leaves eventually turning black or brown. There is no cure of this disease: infected plants should be removed from the garden immediately. Do not replant a new rhubarb plant in the infected area and do not put the infected plant in the compost.

Rhubarb on the Prairies is typically used in desserts, jams, jellies or sauces. Oxalic acid is what gives the rhubarb its tart flavor. Oxalic acid can be poisonous when ingested at high levels. Large amounts of oxalic acid in our body can result in poor calcium uptake and kidney stones. Rhubarb leaves and roots have high enough levels of oxalic acid to be poisonous. Ensure leaves at the top of the petiole and rootstalk at the base of the petiole are completely trimmed off before cooking. Cooking or steaming rhubarb petioles reduces the level of oxalic acid in the petiole. Petioles can safely be eaten raw in moderate amounts. The flower stalks on rhubarb can also be eaten. The flower stalks usually have the texture of cauliflower along with a strong, sour flavor.

Jackie Bantle is a horticulturist working in the Department of Plant Sciences at the University of Saskatchewan. This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society. Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page

Dwarf Sour Cherries: Enter ‘D’Artagnan’

Sara Williams

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

Also called pie cherries, these are most often used in cooking and processing. Traditionally, Canadians call them “sour” while Americans call them “tart.” regardless of the fact that many of the new ones are sweet enough to eat fresh. The shorter varieties bred at the University of Saskatchewan are referred to as dwarf sour cherries or bush sour cherries.

Sour cherries are believed to be descendants of natural hybrids between sweet cherries (Prunus avium) and Mongolian cherries (Prunus fruticosa). But P. cerasus and P. fruticosa easily interbreed so those two may be the same species.

‘D’Artagnan’ (along with ‘Cutie Pie’ and ‘Sweet Thing’) is one of the latest varieties from the University of Saskatchewan’s fruit breeding program – plants should be available within the next 12 months. Named after the fourth musketeer in Alexandre Dumas’ novel, it is closely related to most of the Romance cherries and has the same parentage as ‘Juliet’, ‘Valentine’, and ‘Crimson Passion’. Considered the best variety for homeowners who want a hedge of cherries, it suckers more readily than those in the Romance series. Because it is propagated on its own roots, the suckers will have the same high-quality fruit as the parent plant. Within a few years, it will fill in the row, forming a hedge of thin, flexible branches. And, it needs far less pruning than other varieties. Not until the plants are about 12 years old is there a need to thin out older branches. (Most of the other varieties need pruning when 7 years old.)

Tested for over 15 years, ‘D’Artagnan’ has had consistent production with superior hardiness to ‘Carmine Jewel’. It is shorter than most of the romance series, reaching only about 6 feet (180 cm) in height while other varieties eventually attain 8 or 9 feet (240-275 cm). The burgundy fruit tastes similarly to ‘Valentine’ and ‘Juliet’. Most years it ripens in early to mid-August.

To form a hedge, plant them about 3 feet (1 m) apart within a 3-foot (1-m) wide row. Mulch well to prevent grass or weed competition. Once suckers appear between the plants, allow them to fill in the rows.

Sour Cherry History 101

In the 1940s, Les Kerr (then superintendent of the PFRA Sutherland Tree Nursery) began hybridizing sour with Mongolian cherries with the goal of developing sour cherries hardy to zone 2. His job description limited his breeding to trees and shrubs useful in prairie shelterbelts. Chastised by his superiors for working with sour cherries, Les went underground. He continued his clandestine cherry breeding, giving his seedlings to various farmer friends for planting out. In 1983, while gravely ill and hospitalized, he met with Dr. Cecil Stushnoff, then head of the Horticulture Department. During that bedside meeting, Les revealed which farmers were maintaining his best seedlings. Les passed away a week later.

Dr. Stushnoff and technician Rick Sawatzky gathered Les’ best selections and relocated them to the University test plots. Les’ hybrids were a great improvement over the Mongolian cherries. By the late 1980s, Rick had begun crossing Les’ best selections with sour cherries from northern Europe with the goal of improving fruit size and flavour. He released ‘Carmine Jewel’ in 1999, just as Dr. Bob Bors became head of the fruit breeding program. Together, Rick and Bob began selecting the cherries that would eventually become the Romance series. These new cherries fulfill, and in some way surpass, Les’ original goal to develop sour cherries hardy to zone 2.

Retired from the University of Saskatchewan, Sara’s most recent book is Growing Fruit in Northern Gardens with Bob Bors. She’s been hosting garden tours for over 20 years – to Great Britain, Ireland, Europe, Turkey and Iceland. Join her for a tour of French gardens this September [Contact Ruth at 1-888-778-2378, www.worldwideecotours.com]

This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening event

How to prevent powdery mildew disease from taking over

Powdery mildew infection of peony seed heads.

Jill Thomson

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

This growing season, there seem to be many plants affected by mildew early in the season, particularly in my shady front yard. The affected leaves are easily recognisable by the typical, white fungal growth, usually first noticed on the upper surface of infected leaves.

Powdery mildew is the common name for this fungal disease that attacks many different species of plants. Although the symptoms are usually very similar, there are very specific mildew fungi that cause disease on different hosts For example, mildew on grasses is caused by Blumeria (Erisyphe) graminis and on roses by Sphaerotheca (Podosphaera) pannosa. Lilacs are infected by Erisyphe syringae, whereas Sawadaea bicornis affects peonies. These mildew fungi have very similar life cycles: in the summer the fungus grows on living plant material and spreads from leaf to leaf, and from plant to plant by tiny airborne spores called conidia. These spores germinate on new plant surfaces and can penetrate the leaves, where they form specialized structures called haustoria. Haustoria have a central body with multiple finger-like projections that extract nutrients from the plant cell enabling the fungus to feed off the living plant.

Mildew is known as an obligate parasite because it must feed on living tissue. Mildew does not usually kill its host, but it will hasten the host’s decline. As the amount of infection increases, towards the end of the season, the fungus produces hard walled, black, pinhead-sized structures that can easily survive winter conditions. In the spring these structures produce a spore that initiates new infection, and once the infection is established, the summer spores are responsible for local spread of the disease.

In some plants, infected leaves can become misshapen: rose and high-bush cranberry leaves infected by mildew are curled and distorted as they expand. Peony flower heads seem to be more heavily infected after the petals begin to fall.

There are a number of ways to reduce mildew infection, and these apply to many types of garden plants – grasses, bushes, vegetables, annuals and perennials. Controlling the environment around your plants is a major tool to prevent or reduce mildew infection.

• Start by giving your plants space to allow good air circulation around and through the plants.

• Trim away bottom branches of lilac and rose bushes.

• Grow your plants in open, sunny areas, as long as these are also the right conditions for your plants.

• Although mildew spores do not need free water on the leaf surface in order to germinate and infect, they thrive in high humidity. To reduce infections, always water around the base of your plant in the morning, so the leaves can dry off quickly.

• Avoid using excessive nitrogen fertilizer as this encourages tender, new leafy growth, which is more easily infected than older, tougher growth.

• Remove infected material and clean up fallen leaves in the fall. This debris provides material for the overwintering stage of the fungus and will supply a new source of mildew infection in the spring.

• Mulching around bushes in the fall also keeps the spores from reaching leaves in the spring.

• There are some chemicals that can be purchased to help control mildew on favourite plants as well as many home-made recipes on gardening websites. Always treat a small area of the plant first, to see if it reacts adversely, allowing 24-48 hours to check for a response.

• When shopping for new plants, choose varieties that show resistance to mildew, if you are experiencing a persistent problem in your garden. There are roses that are less likely to develop mildew, however, they are not completely resistant.

These preventative measures also apply to the vegetable garden. Allow for good air circulation around your plants, in particular with cucumber, squash, pumpkins, muskmelon. These vine crops need to retain productive leaves to grow to maturity, so space them out to avoid early mildew infection. Young pea plants usually resist mildew infection; however, older plants almost always succumb to the disease, often after the main productive stage is over.

Mildew in your garden is something you cannot usually avoid, but keeping it to a manageable level is possible most years.

Jill Thomson is a plant disease specialist (retired) who enjoys gardening with her family in Saskatoon.

This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events

Hardy Clematis that flourish on the Prairies

Sara Williams

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

Clematis (from the Greek word for vine) are among our most beautiful vines. While many do very well on the Prairies with average care, others, such as the Jackmanii, need a great deal of coddling, coupled with your most protected micro-climate, and still may not survive our winters. On benches in garden centres and nurseries, they all share equal space. So how does one know if the plant you’re considering is ruggedly hardy or needs shelter? Begin with the Latin or botanical name – which should always be listed on the plant tag in italics.

The hybrids from Clematis alpina and Clematis macropetala (both native to China), are among the loveliest and toughest. They vary in height from 2.6 to 4 m (8 to 12 ft.) and climb by means of twinning leaf petioles, so allow space behind their supports for the leaves to do their job. Both species bloom on the previous year’s growth from late spring to early summer. The hybrid varieties of both species need little pruning unless they’re blocking a window or an arbor, usually every three or four years. They benefit from being planted in deep, organically enriched soil with a 10 cm (4 in.) layer of organic mulch at their base, and deep watering (to a depth of 45 cm/18 in.) every two weeks. Bloom is greater if the vine is in sunlight. These clematis are hardy, easy to grow and vigorous. No fuss, no muss.

The alpine clematis (Clematis alpina), native to the alpine slopes of Europe and Asia, was introduced to England in 1792. It has bell-shaped flowers in shades of white, pink or blue. Its compound leaves consist of three groups of three leaflets and twine around its support as it grows. They generally reach heights of 2 to 2.5 m (6 to 8 ft.). Among the cultivars are ‘Ruby’ with deep pink-dusty rosy red flowers; ‘Willy’ with pale mauve-pink flowers with a darker edge; ‘Constance’ with bright pink, almost red flowers; ‘Francis Rivis’ with larger deep blue flowers; ‘Pamela Jackman’ with rich, deep purple-blue flowers; and ‘Helsingborg’ with deep purple flowers.

The large-petaled clematis (Clematis macropetela) was first discovered in China by a French missionary, Pierre Nicholas Le Chéron D’Incarville, in 1742. But it was not introduced to Europe until just before World War I. It is slightly taller, generally between 3.6 and 4 m (10 to 12 ft.), with bell-shaped flowers. Many of its varieties have been developed by Prairie plant breeders such as Frank Skinner and Stan Zubrowski. Among the Skinner introductions are ‘Blue Bird’ with deep lavender blue flowers, ‘Rosy O’Grady’ with long dark pink pointed sepals, and the snow white ‘White Swan’. ‘Joe Zary’, honouring one of Saskatoon’s promoters of horticulture, has double purple flowers and was introduced by Stan Zubrowski of Prairie River. Other Clematis macropetala varieties include ‘Lagoon’ and ‘Maidwell Hall’ with blue flowers, and ‘Markham’s Pink’ with pink flowers. ‘Jan Lindmark’, a Scandinavian introduction, has dark bluish-pink flowers, while ‘Purple Spider’ has double purple flowers.

Quite different from all of the above are the hybrids of the herbaceous Clematis integrifolia and the climbing Clematis jackmanii. These begin growth each spring at ground level and climb to about 1-2 m (3-6 ft), blooming on the current season’s growth in late summer. Although the roots survive, the above-ground portion is killed to soil level each winter and must be pruned off in early spring. One of the best known of these is ‘Blue Boy’, introduced by Frank Skinner in 1947. A lovely blue, it blooms in late summer. A more recent introduction from Crimea, Ukraine is ‘Pamiat Serdta’ with light violet flowers.

Note: The golden clematis (Clematis tangutica) is listed on Alberta’s noxious weed list and is discouraged by the Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan because of its vigour and abundant self-seeding.

Retired from the University of Saskatchewan, Sara’s most recent book is Growing Fruit in Northern Gardens with Bob Bors. She’s been hosting garden tours for over 20 years – to Great Britain, Ireland, Europe, Turkey and Iceland. Join her for a tour of French gardens this September [Contact Ruth at 1-888-778-2378, www.worldwideecotours.com]

This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events

Don’t let slugs force you to sell your house!

Erl Svendsen

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

I joke that I sold my last house because I found myself sharing the garden with a multitude of slimy slugs. That wasn’t really the reason for moving… at least not the only one.

Slugs are gastropods, not insects. They are related to snails and clams rather than to flies or beetles. They should not be confused with pear slugs which are insects (the larval form of a sawfly), found on cotoneaster, pear, mountain ash and other related woody plants.

Slugs are nocturnal and the most telling clue that they are resident in your garden, aside from their damage, is the silvery trails they leave behind. Their preferred habitat is damp – which unfortunately describe a lot of territory.

Growing up on the West Coast where slugs come in many shapes, sizes and colours, I particularly remember the banana slug named for its resemblance to said fruit in colour AND size. Thankfully, in most Saskatchewan gardens, you’ll typically only encounter the diminutive grey garden slug (Deroceras reticulatum): small, 1-2 cm long, dark to light grey, shiny and, of course, slimy. Don’t let their size fool you. What they lack in size, they can rapidly make up in numbers, laying 200-300 eggs at a time. And in numbers, they are voracious, decimating leafy plants (e.g. hostas) and many other garden plants including root crops like potatoes and carrots (unfortunately not dandelions in my experience).

Selling your home is not a guaranteed or a long-term solution because slugs or their tiny eggs can move in from the neighbour’s yard, on plants from the nursery or your friends, on borrowed tools and even on the bottom of your shoes.

There are ways to fight back. Start by making your garden less hospitable by removing daytime hiding places such as wooden boards, bricks, stones, and garden gnomes. Remove all decaying vegetation throughout the season especially in the fall.

Trapping slugs is a good next option. They are attracted to yeasty, fermenting odors. But don’t waste your beer: add a package of bread yeast to a cup of water sweetened with sugar, stir and set aside to bubble away for a couple of hours. Add an inch of the yeast solution to any shallow container (e.g. empty cat-food or tuna tins). Place several in the garden in the early evening, about 10 feet apart. Next morning, empty the containers (hopefully filled with drowned slugs) and repeat. Another option is to place short boards in the garden. In the morning, just scrape any cowering slugs off the bottom-sides into a bucket of soapy water or straight into the garbage. Repeat. Another effective trap is an upside down rind of a half grapefruit. Slugs can’t help themselves and will be found munching away in the morning on the inside. Simply dispose of rind, slugs and all. Repeat.

There are a number of other control options, most of which are safe to use around the home, your children and pets. Slugs are said to avoid wood ash and coffee grounds (some coffee shops give bags of grounds away for free). If nothing else, the ash and grounds will help enrich your soil. To a slug, crushed baked eggs shells sprinkled around the garden act like razor wire, as does diatomaceous earth (DE), a powdery substance composed of sharp fossilized microscopic hard-shelled algae or diatoms. There are several registered insect and slug control products that are 100% DE (e.g. Safer’s Insectigone). Pool-grade DE is not effective in controlling slugs and other insects because it has been exposed to high heat during processing, altering it significantly. Wear a facemask to avoid breathing in the fine particles when sprinkling them around the garden. Reapply after heavy rains.

After a meal of eco-, human- and pet-friendly iron-based slug and snail killer, slugs stop feeding permanently and die (look for products containing sodium ferric or ferric phosphate). As a last resort, there are also registered metaldehyde-based slug control products. While very effective, metaldehyde is poisonous to slugs, people and pets alike and should be used with care.

Erl gardens in Saskatoon and enjoys being a climate zone denier by trying new and interesting perennials. This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events.

Pines for the Prairies: Mugo pine

Mugo pine (Pinus mugo) is native to the mountains of southern and eastern Europe, from Spain to the Balkans. The species name, mugo, is the old Tyrolese name for this pine. Tyrol is a region in the Austrian Alps to which it is native.

Mugo pines have been gown on the prairies for over a century. You can still see venerable specimens in older neighbourhoods. Some are as high as a two-story building. These hark back to an era when they were grown from seed and the seedlings could be extremely variable in size and height. Today’s nursery offerings are almost always “vegetatively reproduced” from softwood cuttings and are genetically identical to their parents.

(If you’re looking for a smaller upright pine, consider either Swiss stone pine (Pinus cembra) or limber pine (Pinus flexilis). Both are dense and slow growing and ideal for a smaller landscape.)

The brownish-grey bark is covered with bumpy stumps – from which older needle bundles have fallen. The green needles, in bundles of two, are rigid, slightly curved, and retained for five years or more. Their tips sometimes become yellow-green in winter. The small round cones have prickles on their scales.

Mugo pines prefer a deep loam soil but are quite adaptable, growing well in heavy clay as well as sandy soils. They are at their best in full sun. Those growing in partial shade, are often less compact. Once established, they are quite drought-tolerant.

For a denser, more compact appearance, they should be pruned each spring once the “candles” have fully elongated but before the needles have begun to emerge laterally. At least 6 mm (1/4 in.) of the candle should be left.

Larger varieties are used in mixed or shrub borders, foundations, and for mass plantings, while dwarf ones are ideal for rock gardens or perennial borders.

The species and older subspecies such as mughus and pumilo, are generally seed grown and often from different strains of seed. What’s available is a dog’s breakfast, complicated by the fact that many of these may have been pruned to look cute and dense, but will eventually grow up to fulfill their genetic make-up. As well, differentiating between var. mughus and var. pumilo depends on their flower (cone) characteristics, not on size or form. In contrast, most cultivars are dwarf, vegetatively propagated and uniform.

• Pinus mugo mughus is a low growing form from the eastern Alps and Balkans, usually about 1.5-4 m tall and 1.5 to 3 m wide (5-13 x 5-10 ft.), but variable depending on the seed source.

• Pinus mugo pumilio, also from the mountains of eastern and central Europe, is generally 1.5 m high and 1-2 wide (5 x 3-6 ft.), but variable if raised by seed.The following varieties are vegetatively propagated and uniform:

• ‘Mops’ is compact and symmetrical with a neat mounded round form. Very slow growing, it is generally 1-1.2 m high with a 0.75-1.2 m spread (3-4 x 2.5-4 ft.).

• ‘Slowmound’ is low and dense, very slow growing, with rich green foliage (1.2 x 2 m / 4 x 6 ft.)

• ‘Compacta’ is dense and globular (2 x 4.6 m / 10 x 15 ft)

Retired from the University of Saskatchewan, Sara’s most recent book is Growing Fruit in Northern Gardens with Bob Bors. She’s been hosting garden tours for over 20 years – to Great Britain, Ireland, Europe, Turkey and Iceland. Join her for a tour of French gardens this September [Contact Ruth at 1-888-778-2378, www.worldwideecotours.com]

This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events

Beets: easy to grow and tasty

Sara Williams and Jackie Bantle

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

If you haven’t seeded your beets in the garden, it’s not too late. Beets (Beta vulgaris) are one of those root vegetables that can be seeded early in May but because of their relatively short growing season (55 days or so), they can be seeded as late as mid-July for a fall harvest.

Beets are a member of the goosefoot family (Chenopodiacea) because their leaves were supposed to resemble those of geese. The word beet is from the Celtic word, bett, meaning red.

For those of us who make beet leaf “roll-ups” stuffed with rice, it’s reassuring to learn that beets were indeed first cultivated for their leaves rather than their roots, as seen in 8th century BC cuneiform tablets from Babylon. They were well established in the Mediterranean region by Greek classical times where they were used medicinally and for flavouring.

The large roots that we use today were not known until the Christian era. Beets gradually spread through Europe where they were first called “Roman beets”, indicating that the swollen red taproots had been developed and introduced from Italy during the Roman era.

In his 1597 Herbal, Gerard wrote that “The greater red bet or Roman beet, boyled and eaten with oyle, vinegre and pepper, is a most excellent and delicate salad.”

These early beets tended to be coarse, misshapen and hairy. The smaller globes were not developed until the 1800s. By 1828, four varieties were listed in American seed catalogues. ‘Detroit Dark Red’, still a favourite today, was first listed in an American catalogue in 1892.

Beets can be seeded early in spring although if seedlings experience many days of cool weather (5°C or below), this may encourage plants to bolt, forming flowers and seed heads instead of good sized roots. Extreme heat in summer can also cause bolting. Plant beet seeds 5 mm deep, either in a scatter row or 30-45 cm between rows. Thin plants to 5-7.5cm spacings within the row. There is no need to ‘hill’ beet roots with soil if they push out of the ground; the feeder roots remain below ground.

Staggered plantings for beets are recommended to provide a long harvest period of tender, juicy roots: older beet roots tend to be oversized and may also have a tough, woody texture. By seeding a new row of beets 2-3 weeks apart until mid-July, one can ensure that the beets you harvest will have excellent texture and flavor right through to fall.

Young beet seedling leaves are a favorite of sparrows: don’t be surprised to see your morning beet seedlings disappear by the time you come home from work in the late afternoon. To prevent bird damage, cover beet rows with crop covers or supported bird netting early in the season.

Beet roots come in a variety of colours; from red to striped white and red, pink, black to orangish yellow and white. The flavour among all of the beet types is very similar. Beets that are used to make sugar (ie. sugar beets) are different than garden beets. Sugar beets have a sugar content of 15-20% and are a long season crop whereas garden beets usually contain only 5% sugar content. Garden beets are not only grown for their edible root but they can also be grown for their edible leaves; used in salads and beet-dough roll-ups. ‘First Crop’ and ‘Early Wonder Top’ are two beet cultivars recommended for their large, flavourful leaves.

Beet harvest can start as soon as roots are the size that you desire. Most beet roots have reached their prime flavor when they are 5-7.5cm in width. Cut petioles at approximately 4 cm above the top of the root. As with all root crops, do not cut off the root at the bottom as this will lead to desiccation in storage as well as beet ‘bleeding’. Beets will tolerate some autumn frost and will sweeten up with cool autumn temperatures.

Ideal storage conditions for beets are just above 0°C and high humidity. Storing root crops in a plastic bag in a fridge or in moist sand in your garage (just above 0°C) are good locations. Remove excess soil before storage. If you must wash roots before storage, wash gently: new wounds will encourage bacterial rots.

Betacyanin, the pigment responsible for the red colour, is extremely water soluble. Which is why borscht is red. And in some individuals, lacking the requisite genes to properly metabolize betacyanin, beets turn their urine pink.

Retired from the University of Saskatchewan, Sara’s most recent book is Growing Fruit in Northern Gardens with Bob Bors. She’s been hosting garden tours for over 20 years – to Great Britain, Ireland, Europe, Turkey and Iceland. Join her for a tour of French gardens this September [Contact Ruth at 1-888-778-2378]. Jackie Bantle is horticulturist living on an acreage north of Saskatoon.

This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events. The Spring Plant Exchange will be held on Sunday, May 29. The plant exchange will start around two o’clock for more information please see the website. These are “member only” events, but memberships are available at the door for $10.00.

Be a Popeye and eat your spinach!

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

Popeye the sailor man, invented by Elzie Crisler Segar, first appeared as a comic strip character in 1929. By 1932, Popeye was telling the world about spinach. Placed in a hopeless situation, a can of spinach would miraculously appear. Popeye would quickly consume its contents, gain superhuman strength and save the day. Thus, several generations of children were told by their parents to “eat their spinach.” Thankfully, frozen and fresh spinach are now available through our prairie winters and it is easily grown in our gardens. Spinach is an excellent source of vitamin C, high in calcium, magnesium, potassium, a good plant based source of iron and is one of the earliest vegetables to seed in the garden.

The genus name may have been derived from isfanakh, a Persian word for “green hand.” Spinacia is from the Medieval Latin, probably originating from the Latin word spina, referring to the spiny seeds. Oleracea means vegetable-like.

Our garden spinach (Spinacia oleracea) is believed to have developed from a wild form, Spinacia tetranda, still found in the Caucasus, Iran and Afghanistan. It was first cultivated by the Persians (in what is modern Iran) and 647AD had spread via Nepal to China. It was brought to Spain by the Moors. By 1351, it was common enough that “spinachium” had appeared on a list of food that monks were permitted to consume on fast days. In his Herbal of 1597, John Gerard in England described it as “watery and tasteless,” but wrote that it would be good for those with a hoarse voice or who had trouble breathing.

Spinach can be seeded early in spring, as soon as the ground is thawed: plants can withstand a few degrees of frost. Sow seeds 1.5-2 cm deep. For full sized spinach plants, space rows 30cm apart. For baby spinach leaves, rows can be closer together or scattered in a 30-60cm wide bed. With air temperatures above 10°C, seedlings should emerge in several days. Depending on the cultivar, baby spinach leaves will be ready for harvest in as little as 4 weeks after sowing.

Spinach can be grown as a ‘cut and come again’ crop ie. that means that spinach can be cut again and again and leaves will grow back from the same roots. When spinach is grown as a ‘cut and come again’ crop, it is usually harvested as baby spinach and can be grown as close as 3-4cm apart. To produce full sized spinach leaves, thin plants to 7-10cm between plants. Harvest spinach leaves by cutting petioles with a sharp knife just above the soil line.

Because spinach is such a fast grower, consider doing multiple plantings throughout the growing season for a consistent supply. Seed a short row every 2 weeks from early May to mid-August. Plants that are seeded between July 1st and August 15th may need to be harvested as baby spinach as spinach tends to bolt (flower) under high day temperatures. Bolting spinach as been a problem as long as spinach has been grown. In 1784, the D. Landreth Seed Company in United States had developed a slow-bolting spinach variety called ‘Bloomsdale’ which is still available today.

When purchasing spinach seed, gardeners may encounter three different types of spinach: savoy, semi-savoy or flat/smooth-leaf spinach. Although there is not much difference in the flavour or nutrient value of the different types; the leaf appearance is unique to each type. Savoy spinach has curly, crinkly leaves that are slightly thicker than other types. Semi-savoy spinach plants are slightly more upright and have less crinkly leaves than the savoy spinach types. As the name suggests, flat or smooth-leaf spinach has flat leaves. The flat leaves are the easiest type to wash: flat leafed spinach is the main type to be used in frozen spinach.

New Zealand spinach (Tetragonia tetragonioides) is a slightly vining leafy plant that produces copious amounts of greens during the summer: it is not a true spinach. New Zealand spinach requires warm temperatures and a longer time period for seeds to germinate as compared to Spinacea oleracea. New Zealand is sometimes referred to as perennial spinach however, it is not perennial on the Prairies.

Malabar spinach (Basella alba) is a perennial vining plant native to tropical areas of Africa and Asia. The leaves are oval to heart shaped, semi-succulent and mucilaginous when cooked. When eaten fresh, Malabar spinach is similar in flavour to Spinacia oleracea but with a slight peppery, citrus flavour. Malabar spinach is very frost sensitive and should be started indoors about 6 weeks prior to transplanting out for best results.

Recommended fresh spinach cultivars include: ‘Tyee’, ‘Space’, ‘Kolibri’ (baby type), ‘Escalade’, ‘Avon’

Retired from the University of Saskatchewan, Sara’s most recent book is Growing Fruit in Northern Gardens with Bob Bors. She’s been hosting garden tours for over 20 years – to Great Britain, Ireland, Europe, Turkey and Iceland. Join her for a tour of French gardens this September. Contact Ruth at 1-888-778-2378, or www.worldwideecotours.com. Jackie Bantle is horticulturist living on an acreage north of Saskatoon.

This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events. The Spring Plant Exchange will be held on Sunday, May 29. The plant exchange will start around two o’clock for more information please see the website. These are “member only” events, but memberships are available at the door for $10.00.

Arbor Week – Plant a tree or two or three or more

Sara Williams

I’ve been planting small trees every spring for almost half a century. At one time, hundreds; more recently, only a few. But the process inevitably brings a smile to my face, along with a sense of satisfaction, caring and hope for the future. And years later, I now live in a forest, surrounded by the bright orange bark of Scots pines, the cork-like bark of the Amur cork tree, the lobed foliage of bur oak, fruit of crab apples and mountain ash, the rustling of leaves, tweets of birds (instead of phone-obsessed humans), and flowers of various plum, apple and pear species. A feast for the senses that changes with the seasons.

Although schools and communities within Saskatchewan have long marked spring with tree planting, Arbor Day was not officially observed until 2021. The Government of Saskatchewan has made the last full week of May a permanent Arbor Week (the official Arbor Day is the Friday of that week) and Saskatoon is pulling out all the stops to mark the occasion. In celebration, plant a tree, take part in one of the many scheduled activities, or simply stroll through the University’s Patterson Gardens (enter from Preston, across from the Field House), an arboretum containing more than 800 trees labeled with English and botanical names.

Save Our Saskatoon Trees Coalition (SOS Trees), formerly known as SOS Elms, will again be organizing events to celebrate Arbor Week within our urban forests. The theme for 2022 is “Trees Breathe Life”. All events are free and open to the public. Registration and additional information are on their website: https://sostrees.ca/arborweek.html.

May 21-29: Interpretive Walk is a self-guided audio nature-walk describing the contribution of specific trees to our urban ecosystems. Ideal for families or small groups, signage will be in front of the trees included in the walk (bring your phone to scan the QR codes to access the audio clips). Parks hosting this event are Silverspring (710 Konihowski Rd) and Victoria (16th W & Ave H South).

Tuesday, May 24, 7 pm: Branimir Gjetvaj, representing ‘Wild About Saskatoon’, will lead a workshop on Creative photography of trees. With a background in ecology and genetics, his interest in photography focuses on appreciation and protection of natural environments and cultural legacies. Location: Chief Whitecap Park south of Saskatoon; meet in the dog park parking lot. Participation/pre-registration required (SOS Trees website); limited to 15 to 20 people. In case of rain, the alternate date is May 26.

Wednesday, May 25, 7 pm: Tree Spirit Connections: Exploring Spirituality in the Trees

Rev. Shawn Sanford Beck, known as the Green Priest, employs spirituality – using breathing, prayer, body movement and the active imagination – to connect with and bless the natural world around us. Location to be announced on SOS Trees’ website.

Thursday, May 26, 7-9 pm: Our Trees in a Changing Climate, a University of Saskatchewan webinar.Dr. Colin Laroque, Soil Science Department, University of Saskatchewan, explores the carbon sequestration by trees. How do they contribute to climate mitigation? What adaptation strategies can homeowners and city planners employ to maximize our efforts? The financial benefits to homeowners of planting trees? Free, but register through gardening.usask.ca.

Friday, May 7, 7 pm: Remai Modern Art Gallery Film Night. “What Trees Talk About”, directed by Ryszard Hunka, deals with the secret, dynamic life of trees in our boreal forests – how they communicate, wage war and work together to transform their world and ours. Check the Remai website for covid protocols.

Saturday, May 28, 9 am-noon: Arbour Crest Tree Pruning Workshop. This hands-on pruning workshop, instructed by local arborist Robin Adair, takes place at the Varsity View Community Garden (Wiggins Ave and 12th St. E). It covers the what, when, why and how of pruning and tool care. Bring your own pruning tools, gloves and safety glasses. Registration is limited (SOS Trees’ webpage).

Sunday, May 29,1 pm: Community Tree Planting of a Food Forest. SOS Trees has partnered with the Sunnyside Care Home, the City of Saskatoon and the Saskatoon Nature Society to plant fruit trees in the care home’s garden, 2200 St. Henry Ave.This initiative will connect vulnerable populations with access to nutritious food, improving food security in a sustainable manner. It also encourages bird populations. Please bring your own tools.

In celebration of Arbor Week, plant trees – with your family, neighbours, school, club or community organization – and breathe in that sense of satisfaction, nurturing and hope for the future of our urban forests.

Retired from the University of Saskatchewan, Sara’s most recent book is Growing Fruit in Northern Gardens with Bob Bors. She’s been hosting garden tours for over 20 years – to Great Britain, Ireland, Europe, Turkey and Iceland. Join her for a tour of French gardens this September. Contact Ruth at 1-888-778-2378, www.worldwideecotours.com

Pines for the Prairies [Part III]

The following pines are all native to North America. And with a little bit of care, all have been successfully grown on the prairies. All prefer full sun, a lighter, well trained soil, and a more protected location.

Limber pine (Pinus flexilis) is an alpine/subalpine species, often found in exposed areas in the foothills of the Rockies. Both the species name, flexilis, and the common name, limber pine, refer to the supple young branches that can be tied in knots. It was discovered by Edwin Jones, an American army doctor who accompanied an 1820 expedition to the Rocky Mountains.

Dense and pyramidal when young, it becomes rather broad and flat-topped with age (like many of us) developing a large and uneven crown. Single or multiple trunked, both the trunk and the branches appear thick in proportion to their length. The bark is a soft grey-green, later turning greyish-brown to black.

The needles, in bundles of five, are a dark blue-green, stiff and slightly curved, with three or four lines of stomata on each surface. They persist for 5 or 6 years, lending the tree is very dense appearance. The cylindrical and resinous cones are erect when young, becoming pendulous, hanging at right angles to the stem, once they mature. The edible seeds can be eaten raw, roasted or ground into flour. Although slow growing, limber pines can live for over a hundred years.

They prefer a light soil but are quite adaptable as long as it is reasonably well drained. They’ll grow in sun or partial shade, are drought-tolerant once established, and have no problems other than the occasional sapsuckers who seem to find them attractive. Limber pines are well used as specimens, accents or within a mixed border.

Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa var. scopulorum) is native to South Dakota’s Black Hills, eastern Wyoming and the Rocky Mountains’ eastern foothills. Ponderosa means heavy, a reference to the wood, while scopulorum means of cliffs or rocks, describing its native habitat. It’s smaller and hardier that the species (P. ponderosa) and better adapted to the prairies. Broadly pyramidal (15 x 6 m / 50 x 20 ft.), its bark is dark grey, nearly black. The needles are very sharp and in bundles of three. The brown cones are round, and each scale has a tiny bristle. Obtain trees from seed collected from its northern-most range.

White pine (Pinus strobus), native to much of central and eastern North America, including Manitoba’s southeastern corner, is probably the softest and most sensuous pine available to prairie gardeners. The species name, strobus, refers to its cones.

A valuable softwood lumber tree, during the colonial era white pine was reserved by law for the exclusive use of the Royal Navy for ship masts. Today, it makes a handsome specimen tree. Place it were it can be touched!

But be aware of provenance, the extent of a plant’s native range! Plants grown from seed that originate in the most northern and western portion of its natural range are more likely to be hardy on the prairies than those from further east or south. My own white pine came as a seedling, dug by a friend from the ditch on the highway west of Thunder Bay. It has grown and prospered for four decades, whereas two earlier attempts with commercially available white pines of unknown seed origin had failed.

White pines are graceful, pyramidal trees (15 x 7 m / 50 x 23 ft.) with thin gray bark that becomes brown and furrowed with age. The long, soft pliable blue-green needles are in bundles of five, point forward to the tips of the branches, and generally remain on the tree for two years. The curved cones are long and cylindrical, an attractive lilac-purple, exude a white resin and are retained for two years.

Fast growing, especially when young, white pines live for well over a century. Place them where they’re sheltered from wind as they are vulnerable to winter browning, more so in their early years. Somewhat adaptable, they do well on fertile, moist, well-drained soil in full sun or partial shade.

Although white pine blister rust and white pine weevils are serious concerns where large populations of white pines exist, neither has been very problematic on the prairies where these pines are relatively uncommon.