By Bernadette Vangool

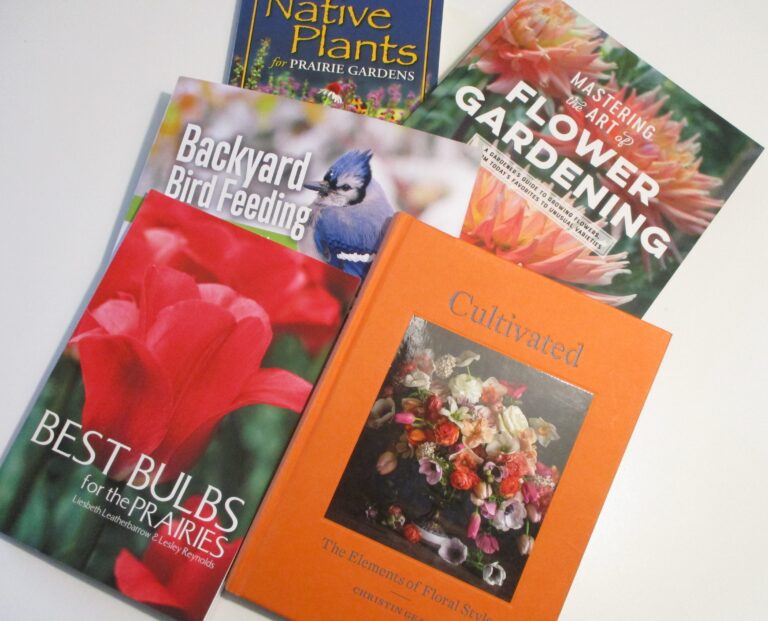

As I was perusing my bookshelf, I thought I would share with you the many book gift possibilities for you, your resident gardener or gardening friends.

For the cut flower grower among them, consider Cultivated, The Elements of Floral Style by Christin Geall. This book delights with photographs of beautiful flower arrangements interspersed with pertinent information on contrast and composition. It is well written, easy to digest and pleasing to the eye. Erin Benzakein, flower farmer and floral designer, says it best: “Christin Geall is the rare talent who has an eye of the artist, the pen of a poet, and the heart of a gardener”. Christin takes you from supplies, to flower selection through colour and design, always with great bouquets, beautifully photographed, to illustrate her points. The author is a designer, writer and gardener in Victoria, British Columbia who teaches floral design through her company Cultivated by Christin.

Complement the book on floral design with Mastering the Art of Flower Gardening, a Gardener’s Guide to Growing Flowers, from Today’s Favorites to Unusual Varieties by Matt Mattus. Here, you’ll learn how to grow cut flowers for the express purpose of making these beautiful arrangements. Matt gardens in Massachusetts. Although he discusses perennials and bulbs, the majority of plants covered are annuals, for which the differences in growing zones are negligible. He shares his experience with seed germination of various flowers, as well as the time to sow and when and how well seedlings transplant.

I’m unsure about the availability of the above books in local book stores, so order early or obtain them on line. The following books are available locally.

Backyard Bird Feeding, A Saskatchewan Guide by Trevor Herriot and Myrna Pearman is an excellent introduction for beginner bird watchers. In just a few years, I have increased the number and variety of birdfeeders in my back yard and the feathered friends visiting have been a great delight and form of entertainment. Originally written by Myrna Pearman and first published by Ellis Bird Farm in Alberta in 2015, it has now been adapted to Saskatchewan. Many of the photographs were submitted through the Sask Birders Facebook page and credits are noted. It covers feeders, types of feed, individual bird preferences, bird baths, feeders to discourage four legged critters and bully birds. Chapter 7 describes a large number of birds that may frequent the backyard feeder. It includes a photograph and discusses their habits and preferred feed, such as suet, cracked corn, millet, sunflower seeds etc. This could also be a great gift for the grandkids.

One little book that has been around since 2001 is Best Bulbs for the Prairies by Liesbeth Leatherbarrow & Lesley Reynolds. Still as relevant today as the day it was published, it includes information on the many bulbs available, from spring flowers such as crocus, fritillary and tulips to iris, lilies, gladiolus and much, much more. Beautiful photographs accompany the descriptions of cultivars and their use in the landscape. “Perfect partners” for particular bulbs are also discussed.

Last but not least is Native Plants for Prairie Gardens by June Flanagan (2005). I just revisited this book, and of course found some new to me native plants to incorporate into my landscape. Each plant featured includes its natural range (eastern prairie, widespread across northern prairie), its habitat (dry slopes, rocky hillsides, stream banks, woodlands) and type of plant (grass, herb, upright perennial) along with hints that will help you best place it within your own perennial border. I discovered that the prairie coneflower (Ratibida columnifera) which I planted last year is a short-lived perennial that will self-seed. So, I’ll have to replace it if I decide to mulch my new border!

More bookshelf favourites to follow……This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check out our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial).