Sara Williams

Saskatchewan Perennial Society

Scots pine and Swiss stone pine are from Europe but have grown well here for generations. It’s always a horticultural high point to see a plant you’ve long loved in its natural habitat. I’ve been fortunate to see natural forests of both of these. And seedlings of Scots pines planted three and four decades ago have now grown to form their own forest.

Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) is among my favourite conifers. The species name, sylvestris, is from the Latin word silva meaning “of the forest” (just as the state of Pennsylvania means “of Penn’s woods”, referring to the Royal Charter given to William Penn).

“Scots” is somewhat misleading as this species is a widely distributed pine with a native range from Scotland in the British Isles through Spain and into Siberia. Most of the Scots pines that have proven hardy on the prairies come from seed that originated in Scandinavia and northern Russia – not Scotland. The wood was once widely used for the masts of sailing ships as the resin slowed their decay. Scots pine are large (15 x 6 m / 50 x 2o ft.), fast growing and long lived.

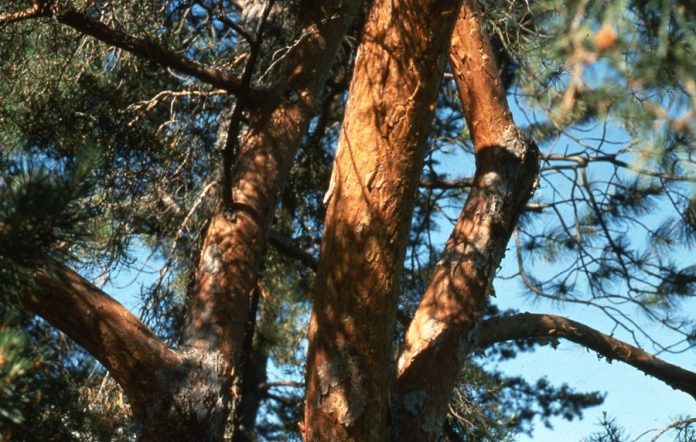

Although they can be almost symmetrical and pyramid-like when young, they become more open and flat-topped as they mature, with all the character of a “Group of Seven” painting. Their bark is a very attractive foxy orange to reddish brown, later becoming rough and fissured. With age, they develop a deep and wide-spreading root system, especially when grown on sandy soils.

Needles are in bundles of two with a sharp point. They are blue-green, stiff and slightly twisted, often becoming yellow-green by late winter. The cones, pointing backward toward the trunk, are in clusters of two or three. They are retained for two years and then fall. They have no prickles on their scales but are rock hard and exceedingly tough on lawn mower blades – another good reason to apply mulch below these trees!

Scots pines do well on sandy, well-drained soil in full sun and are exceptionally drought-tolerant, even when fairly young. They are occasionally infested with white scale insects, and sap suckers have been known to leave their mark on them, but are otherwise trouble-free.

They are excellent as specimen trees (when perfectly formed and symmetrical) or as character trees (when not perfectly formed and asymmetrical), as well as in groupings. They have been planted in shelterbelts for nearly a century and are well appreciated by birds when used in wildlife plantings. They are xeriscape trees par excellence. [355]

Native to the Carpathian and Alps Mountains as well as parts of Asia, the Swiss stone pine (Pinus cembra) is long lived but very slow growing – it’s a tree you plant not for yourself but for future generations and your grandchildren.

Narrow, columnar, dense, and clothed to ground level (if not browsed by deer), it’s one of the loveliest pines available. Up to 12 m in height and 5 m wide (40 x 16 feet), the bark is gray-green and smooth. The long soft needles are dark green with bluish-white stomata lines on their undersides. In bundles of five, they’re resistant to sunscald and retained for up to 5 years, giving the tree a very dense appearance. The erect cones are greenish-violet when young, maturing to purple-brown. They are prickle-free with edible seeds (pine nuts) and drop in their third year without opening. Once on the ground, seeds are released through decay or dispersed by birds.

Plant in full sun in well drained loamy soil. Once established, they’re moderately drought-tolerant. Although it has a painfully slow growth rate from a gardener’s point of view, the Swiss stone pine is considered one of the best pines for a small landscape. Certainly, it will not outgrow its location in your lifetime. It’s excellent as an accent tree, as a grouping or in a mixed border.

Sara Williams is the author and coauthor of many books including Creating the Prairie Xeriscape, Gardening Naturally with Hugh Skinner and, with Bob Bors, the recently published Growing Fruit in Northern Gardens. She continues to give workshops on a wide range of gardening topics throughout the prairies.

This column is provided courtesy of the Saskatchewan Perennial Society (SPS; saskperennial@hotmail.com ). Check our website (www.saskperennial.ca) or Facebook page (www.facebook.com/saskperennial) for a list of upcoming gardening events.