Shelley A. Leedahl

Sask Book Reviews

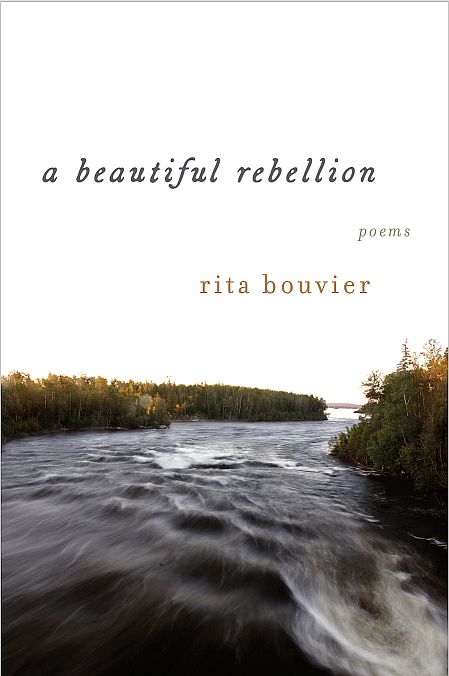

I took an extended pause before opening a beautiful rebellion, the fourth poetry collection by Saskatoon’s Rita Bouvier. The Métis writer and educator grew up beside the Churchill River, and the cover photo of a forceful river flowing between forested banks before a backdrop of white sky is immensely effective. To me, the scene says: Yes, this is the answer to all that ails us. This is holy.

Indeed, a sense of reverence permeates much of the work in this moving and intimate collection, with its odes to jack pine, bear, the moon, aunties and other relatives, and “feathery snowflakes/whirling down from the heavens above”. One of my favourite pieces, “holy, holy, holy,” ingeniously juxtaposes “waves crashing against the rocky shoreline” with “God/reaching in and then out again”. Bouvier’s narrator in “daylight thief at Amigos Café” watches the other patrons-including a dancing child-and considers herself “a thief … in broad daylight/stealing the sacred … all around me.”

This careful poet continually turns to the natural world for restoration and peace as she considers colonialism, patriarchy, “the murky waters of truth and reconciliation,” climate change and the pandemic. She rejoices in “the winged ones,” “the art of gathering/sweet wild berries,” and considers jack pine to be “medicinal aerosol/a rich biochemical molecular picnic”. Awe and gratitude are frequently present, as is the perception of humanity’s oneness.

The writing is highly visual, ie: the aunties wear “sweaters of sky and magenta,” and dew’s personified thus: “droplets of condensed water vapor/on blades of grass on a spider’s web/jewel-like/clinging their way back to the earth.” Lovely, as is Bouvier’s hyper-awareness of sound, evident in “soundscape” (“the saddest sound you will ever hear/is the faint and mournful sound/of a beaver crying”) and several other poems.

The use of “Rebellion” in the title immediately turns my thoughts to Louis Riel, and the leader and “gentle man” appears in the “supermoon rising” section. Interestingly, his sister, Sarah Riel, lived and is buried in Bouvier’s home community of Île-á-la-Crosse, and the siblings’ paternal grandparents met there. Text in Cree and Michif-languages spoken in Île-á-la-Crosse-organically weaves through the free verse and the few prose poems.

Above all, this book feels like an homage to the north, where Bouvier was raised “by the waterfall place/by the holy springs/by the strait of the spirit/in the place of peace.” Her poem “a table in the sky” is one of several that paints the area as a kind of boreal Utopia, and I am there with the poet at a lookout in her “childhood island home” as she “waited for the pinpoint of [her] papa/to return from a day’s work across the frozen lake.”

Ah, yes. Bouvier’s successfully transported me to her sacred place beside the river, in the “small village/without many amenities.” And she makes me believe that if we all had a hallowed place like this to visit, we could, despite our scars and transgressions, eventually-and in community with the water, the creatures, and each other-“climb our way … into the light.” This book is published by Thistledown Press. It is available at your local bookstore or from www.skbooks.com.