This is the 22nd in a series of columns about the 70 British Home Children sent to St. Patrick’s Catholic Orphanage in Prince Albert between 1901 and 1907. While all orphanage records were destroyed in the terrible fire of 1947, every attempt has been made to trace the life stories of these dispossessed children through genealogy websites and newspaper databases.

May and Lillian Holderness: Their Father’s Story

“The insistence of a Charity on its legal right to place the Atlantic between a child and its [parent] does not look well.” – British Home Office, 1897, as quoted in Uprooted by Roy Parker (2010)

“There was no new thing under the sun. About the schools where Indigenous children were shorn and stripped, renamed, reeducated and returned home broken and scarred, or never at all. About children born across borders in their parents’ arms only to be caged in warehouses, alone and afraid. … There was a long history of children taken, the pretexts different but the reasons the same. A most precious ransom. A cudgel over a parent’s head. It was whatever the opposite of an anchor was. An attempt to uproot some otherness. Something hated and feared. Some foreignness seen as an evasive weed. Something to be eradicated.” – Celeste Ng, Our Missing Hearts (2022)

1904 was a pivotal year in the life of Joseph George Holderness (1869-1922). Joseph, a Sergeant Master Tailor in the British Army’s 4th Battalion Rifle Brigade, lost his wife Edith Matilda Collard (1874- 1904) to typhus on 31 July of that year, leaving him a single father of five children, three boys and two girls, May/Mary Edith (1897-1981) and Lillian (1898-1989). That same year, he was informed that he was to be stationed in Malta. So, he arranged for his children to board at a Catholic school in London, England.

Early in 1905, shortly after his wife’s death and before he left for Malta, Joseph married a woman named Sarah, 18 years his junior. He then embarked for Malta where he served from 8 November 1905 to 13 March 1906 – about five months. At his own request, Joseph returned to England and was discharged from the Army at Gosport on 31 March at age 36. He was awarded the Meritorious Service medal. [Source: Royal Hospital Chelsea Pensioner Soldier Service Records, National Archies of the UK, www.fold3.com]

By the time Joseph returned to be reunited with his wife and children, the powers of the British child migration scheme were in full force. There was little to no chance that Joseph could have had his little girls, May and Lillian, returned to him from the Catholic home in which he had placed them. Within a year, the girls were sent to Canada by the Southwark Rescue Society, a Catholic rescue organization.

According to May’s great-granddaughter, Corrine Bainard, Joseph “insisted that he had no knowledge and gave no consent to them being sent away.” When Corrine contacted a Catholic Emigration Society in England, she was told that the girls’ father “might have lied to them out of shame.” “I know from my mother,” Corrine continued, “that the story was always that they were sent without permission.” May’s son Gerald, Corrine’s father, was “angry his whole life at how his mother and aunt were treated and tried in vain to get information that would either prove or disprove the story,” Corrine wrote, “but his questions were never answered.” (Email to me, 27 March 2023)

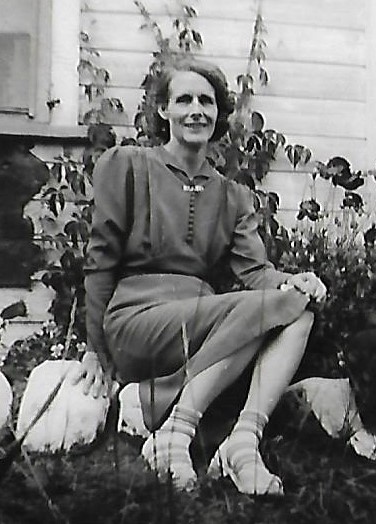

May (Holderness) Hinderks and family, no date. The woman on the left may be Lillian Holderness

Joseph may have tried, but he was unable to reclaim his daughters. Ten-year-old May and nine-year-old Lillian departed from Liverpool, England with 19 other children on 12 July 1907; they arrived in Quebec City, Canada on 18 July 1907. Their destination was St. Patrick’s Catholic Orphanage in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

The girls lived and studied at the Prince Albert orphanage until their late teens. Corrine told me that apparently St. Patrick’s had their father’s information and mailing address but the girls were told nothing of the circumstances of their father and brothers until May was 18 years old.

May Holderness was born on 10 February 1897 in the Portobello Barracks, Dublin, Ireland. She left the Prince Albert orphanage in August 1915 to receive teacher training at Saskatoon Normal School, graduating in the fall of that year. She taught at the little white schoolhouse at Romance, Saskatchewan where she met Hubert Hinderks, a farmer and member of the Rural Municipality’s school board. They married and farmed south of Watson where they had five children.

Lillian Holderness was born on 13 August 1898, also in Dublin. She graduated from the School of Nursing at Holy Family Hospital in Prince Albert in 1919. Illness, possibly the Spanish Flu, forced her to move to her sister’s home to recover. The 1921 Canada census shows Lillian, age 21, living with May (24), Hubert (37) and their two sons. Her occupation was recorded as “none”. The Saskatoon StarPhoenix reported on 12 July 1924 that Lillian was a Carnival Queen contestant at the Watson Sport’s Day. About a year later, she married her sister’s brother-in-law, Carl Hinderks, also a farmer in the Watson district. They had three children, two who survived infancy.

I am so grateful to Corrine Bainard for sending me a small collection of letters from Joseph Holderness to his daughters May and Lillian. His love for his lost girls shines through on the pages. Here are a few excerpts:

• On 31 May 1918 he wrote to May congratulating her on her marriage, asking if her husband was Catholic. “Do you know May I feel very, very proud of you,” Joseph wrote. “To think of the disadvantages against us and then to know that you have come out so grandly. Thank God for it all.”

• 17 August 1918, letter to May: “How I wish I could come over to your world and see you both. I pray that we may all come together again, before the end. It seems rather a remote chance, still I feel assured that, providing we keep up an all round correspondence, and try our best, that something could be brought about. We at present are scattered about but I hope soon to see Harold, Arthur and Ernie then I must try to see yourself and Lily. … Kindest, dearest love to you and my Lily. Good-bye & God bless you. Your affectionate father”

• 17 August 1918, letter to Lillian: “I wonder when I shall have the happiness of seeing you two. Perhaps you will visit the old country again, after you are through with your nursing. … Write to me Lily dear, as soon as you can, you promised me a nice long letter, so I shall be awaiting its coming with longing.”

• 30 January 1920, letter to May: “First of all try and forgive me for my negligence. … I have often been on the point of writing and then put it off, but I promise you I will endeavor to answer your letters right away in future. I was very much upset to hear of Lily being ill. Said she was coming to your house to recover. You will look after her well I know May; perhaps she has been overdoing it in her nursing. I hope she will soon be alright again. … I was telling Lily how I wish we could come together again. I long so much to see you two girls and you are so very far away. … We are just going on in a quiet way, a very uneventful existence, hence lack of news.”

As it happens, Joseph’s life was hardly uneventful, but his was not the kind of news he would have wanted to share with his daughters. On 30 August 1919, the Ealing Gazette of London, England reported: “Insulting behaviour to a lady seated in a passing punt resulted in Joseph Holderness (49), a well-dressed man, described as a tailoring instructor, of Stacklegate-road, Teddington, appearing in the [prisoner’s] dock at Kingston on Saturday. Mrs. Mabel Silander stated that she was being paddled upstream in a punt on the Thames and on passing the Queen’s riverside promenade she saw accused standing at the top of some stone steps behaving inappropriately. As she was sure that his conduct was deliberate she went in search of a policeman.” Joseph was sentenced to three months’ hard labour.

There is a bright spot in the story. May was able to go to England to spend time with her father and brothers before Joseph passed away in 1922. He died of cirrhosis of the liver, likely caused by excessive alcohol consumption, on 10 May 1922 in Teddington, Middlesex, England.

May Holderness Hinderks died of Alzheimer’s on 6 October 1981 in Watson, Saskatchewan at age 84. Her younger sister Lillian died on 4 May 1989, also at Watson. Both are buried there in Sacred Heart Roman Catholic Cemetery.