Doctor testifies that she never thought Jordan Norfield was at risk of dying

An autopsy report discussed at the inquest of Jordan Norfield on Thursday lists his cause of death as “complications from severe rhabdomyolysis” – a life-threatening condition of which Norfield had several risk factors.

Norfield’s time of death was 9:05 p.m. on Dec. 5, 2020 at the Victoria Hospital in Prince Albert.

Four days prior, he was arrested for breaching his COVID-19 self-isolation orders and held overnight in police detention cells from Dec. 1 to Dec. 2.

As shown in video footage of his cell, Norfield was drinking excessive amounts of water, and frequently vomiting and urinating. Half way through the night, he started to lose his balance, shake and appeared to be seizing, which led to hitting his head on the concrete walls.

Rhabdomyolysis occurs when damaged muscle tissue spreads its proteins and electrolytes into the blood.

Forensic pathologist Dr. Derek Musgrove testified that in Norfield’s case, complications included acute kidney and liver failure. Other risk factors included alcohol consumption, COVID-19 and thrashing and seizing in his cell.

“Mr. Norfield was medically managed, however, despite standard of care, he deteriorated and was subsequently pronounced deceased,” reads Musgrove’s report.

The autopsy report also noted superficial injuries, including a gash on Norfield’s head and bruising.

An evaluation of his brain revealed minor swelling, but “there was no internal evidence of blunt force or penetrating injury,” reads the report.

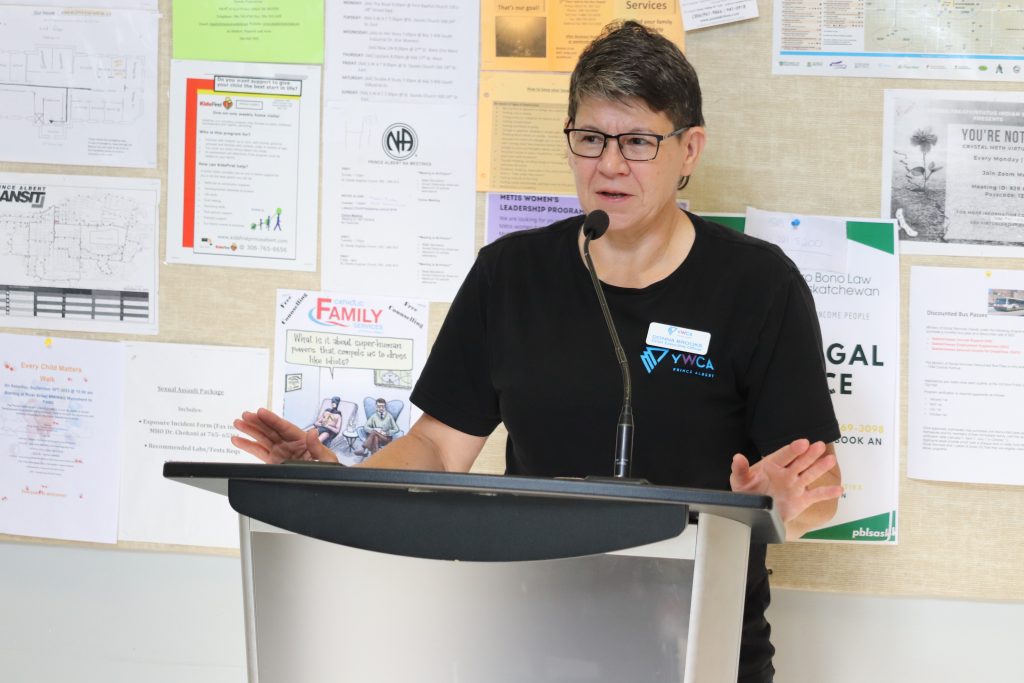

Dr. Comfort Alara, a primary care physician, was the final witness to testify.

Norfield was placed under Alara’s care once he was admitted to hospital. The first time she physically assessed Norfield was on Dec. 3.

“He was awake; he was talking; he was restless,” she said.

Alara said she reviewed the emergency room’s assessment of elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels – the indicator of rhabdomyolysis – and dehydration. She was also aware that he was COVID-19 positive, had a history of alcohol abuse, and had been transferred from the police cells.

“I did not know anything about what happened while he was in custody,” she testified.

Alara said she spoke with Norfield’s mother, who said he had a history of seizures. She said he did not have any seizures in the hospital.

Alara added that knowing the large amounts of water he was drinking wouldn’t have changed her treatment plan.

The standard treatment for rhabdomyolysis is IV fluids to flush the toxins out of the body.

The inquest heard that Norfield’s CK levels were 11,000 U/L when he was assessed in the emergency room. The normal range is 30 to 200.

The next day, on Dec. 3, his CK levels rose to around 41,000, and even more on Dec. 4 to 73,000.

On Dec. 4, Alara said Norfield was “severely agitated” and hallucinating due to withdrawal. He removed his IV and catheter, so staff gave him medication used for alcohol withdrawal to settle him and continue treatment.

The morning of Dec. 5 – the day he died – Norfield’s CK levels dropped down to around 21,000. Tests showed Norfield had minor kidney injuries, said Alara.

But still, Alara left work that day expecting that he would eventually be discharged from hospital. It was never a thought that he was at risk of dying, she said.

Norfield’s CK levels were listed as over 76,000 in the autopsy report.

Jury makes 3 recommendations to police service

The six-person jury determined that Norfield’s death was accidental.

They made three recommendations to the Prince Albert Police Service to improve operations in the detention cells.

The first recommendation is that random audits be conducted no less than four times per year to ensure that operations in the detention cells are being followed.

Secondly, the jury suggested that all police and security staff who may be working in the detention cells be required to review all policies annually.

The last recommendation is about video surveillance of the cells. The jury suggested that the police service consider giving the sergeant in charge of the detention cells “limited” ability to play footage back. Any playbacks should be logged and only accessible by an individual password, they recommended.

Norfield’s inquest was not mandatory since he did not die in the custody of the police. The inquest was requested by the chief coroner of Saskatchewan.

The purpose of an inquest is not to find fault, but to determine the circumstances surrounding someone’s death with the hopes of preventing similar deaths in the future.