The Sturgeon River plains bison herd is one of the few free-ranging bison populations in North America and roams in its historic territory which included areas of the Prince Albert National Park. The herd is currently estimated at 120 animals after reaching highs of over 450 animals from 2006 to 2008.

In 2013 a variety of different groups and agencies began working together and there are currently signs of the herd renewing including an increase in juveniles shows promising signs for a return of the herd.

Parks Canada is committed to the stewardship of the Sturgeon River herd and is working with partners to reverse the declining trend and conserve the bison.

According to Joanne Watson, Resource Management Officer for Prince Albert National Park, the groups involved in co-management strategies include Parks Canada, the Government of Saskatchewan, Sturgeon River Plains Bison Stewards, CPAWS, the Buffalo Guardians, Indigenous communities and neighbouring residents.

“We have all been working together to combine our knowledge and information and ideas. We wrote a management plan in 2013 that set out some actions to move forward with. Since then the population has continued to decrease but working together collaboratively and just continuing to spread the education around it now we are seeing a big shift in harvesting rates, harvesting rates are coming down quite a bit and more male bison have been chosen to be harvested,” Watson said.

“We are really happy to spread that information that working collaboratively really is shining right now. When we are out monitoring the bison we are noticing that there is a lot of juvenile bison right now. That really gives us some promise of herd renewal looking forward to the future,” she added.

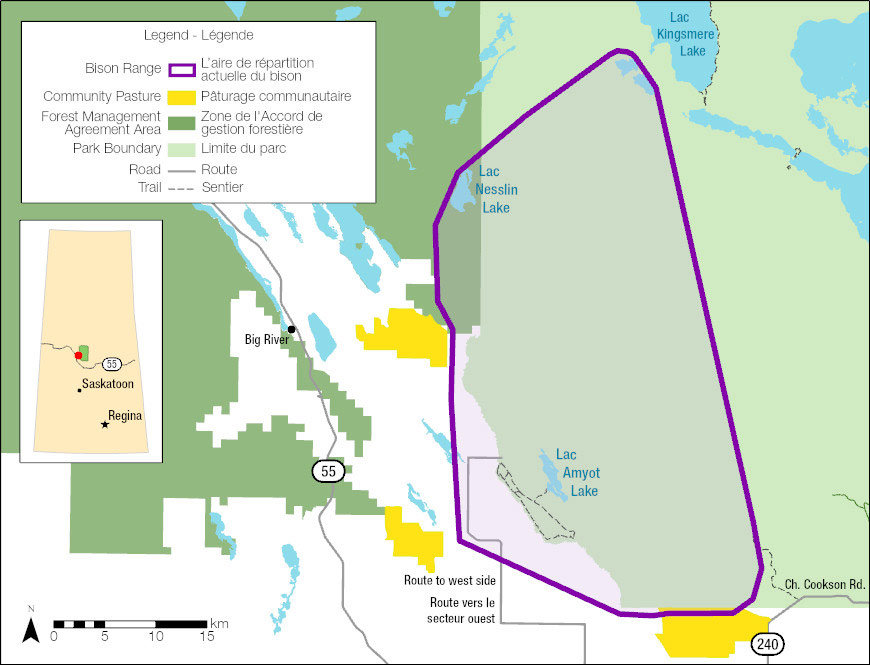

Annual wildlife surveys conducted in the park in February counted 91 bison, the highest number observed in three years. Aerial surveys are conducted to help estimate the population. Each year, a portion of the herd remains undetected from the air, since the Sturgeon River herd is very wary of people, noise and disturbance, and due to the rugged, forested nature of much of the herd’s range.

The origin of the herd according to Watson traces to 1969 when the province released 50 bison into the Thunder Hills region in central Saskatchewan and 10 to 15 bison moved south and established a home range in Sturgeon River which is in the southwest boundary of the park.

“Those 10 to 15 bison formed the Sturgeon River plains bison herd that exists today. The population grew steadily off the start and it peaked between 2006 and 2008 where we estimate the population to be about 450 in total back in 2008,” Watson said.

In 2008 the bison herd experience an outbreak of Anthrax and there were 29 animals confirmed lost but Parks Canada estimates that as many as 60 animals could have been lost.

“That kind of started the population decline. This population is purely wild, they are not managed hands on by humans,” Watson said.

Because the herd is purely wild they are exposed to climate, predators and other limiting factors which all were occurring at the same time. Watson explained that there was also an increase in harvesting of bison as they left protected areas and went to private and provincial land.

“We collected data and realized that the amount of harvesting that was taking place wasn’t sustainable for the population and it was also very evident that breeding females were being chosen for harvest which essentially takes your breeding stock away,” she explained.

She explained that Parks Canada is moving toward increasing on-the-ground monitoring and low stress methods to help monitor the size and health of the herd. On-the-ground monitoring creates more confidence in population size and demographic, including age and sex, and lessens the impact on the reduced herd. Fecal samples were also collected for genetic material to determine herd diversity.

Watson explained that a complete revival is years away but the signs are all positive.

“For a wild population it wouldn’t be probably any faster than approximately five years, it’s hard to say exactly but it’s going to take about five years for sure but we are seeing an upward trend,” Watson said.

One reason they are working to conserve bison because the species are important to the landscape.

“They are known as an ecological engineer and they shape the landscape for all other native plants and animals. We are talking anything from plants to bugs to predators. Keeping bison on the landscape really does fulfil how the ecosystem works. So without bison in the ecosystem it really can’t function as it is intended to,” Watson said.

The selection of older or male bison for harvest and continuation of low overall harvest rates is critical to herd survival and recovery into the future. Bison co-management and research is taking place to help restore a healthy plains bison population that thrives on the landscape inside and outside Prince Albert National Park.

She added that they are important for more reasons than the ecosystem as they are also vitally important and interconnected to the ways of life of Indigenous people and other people. The herd’s importance is reflected in the diverse groups who are part of the group assisting with the project.

“Without bison on the landscape cultural connections are also broken. There’s a lot of aspects why they are important and there’s a lot of pieces to the puzzle on how to keep our wild plains bison populations healthy and I think one of the main pieces of that puzzle is working together. We really need to work together and keep the information flowing across all agencies and groups.”