As a reporter, you get used to covering every nook and cranny of Prince Albert, but on this rare occasion, we’ve stumbled across a street I can’t find without a map.

Technically it’s not even a street. It’s a crescent, and it runs about as far south as you can get while still being inside city limits. Fortunately my two drivers have heard of it. Now the only debate is whether it’s quicker to turn at 28th Street East or head all the way down to Marquis Rd.

“It’s time to earn your salt,” says our current driver, Norma Sheldon.

It’s around 11 p.m. on Saturday night, and for the next half-hour I’m a navigator with Operation Red Nose. Despite the name, my job consists of more than just finding our destination. I’m part map-reader, part accountant and, if necessary, part butler.

The map-reader part of the job takes a brief back seat as we pull up next to a house with Christmas lights on the outside and a Christmas party on the inside.

Sheldon has delivered us to our destination. Now our second driver, Glenn Ferguson, gets out and heads for the front step with me in tow. A young woman in her twenties greets us at the door and tells us she’ll be out in a minute. Inside the good-byes begin while Ferguson and I wait on the doorstep. The temperature hovers around -14 C, and the car we’re supposed to hop into and drive home isn’t plugged in and hasn’t been started.

“Does this normally take long?” I ask.

Ferguson shakes his head and waits patiently. He’s decked out for cold weather while I’m in a thin coat with a red Prince Albert Lions Club jacket fitted over top. It’s not the most comfortable wait, but it could be a lot worse. Temperatures plunged to as low as -25 C the night before, so I can’t really complain.

Eventually the good-byes end and the young woman leaves the home. Her husband follows a few minutes later. Soon they’re both packed in the back seat of their own vehicle while Ferguson jumps behind the wheel and I slide in the front passenger side.

The couple hasn’t had a lot to drink, so butler duties aren’t necessary. There’s no need to help them walk, climb into the vehicle or find something like a cell phone. Now, it’s back to being a navigator, although Ferguson doesn’t need much help from me either. This is his third year as a driver with Operation Red Nose and he’s already identified our only obstacle. We’ll have to head north on Second Avenue West, but the boulevard running down the middle means we can’t make an easy left hand turn into our new destination. Instead, we’ll have to turn early, head north again and eventually double back to the east. Not a major challenge, but one you don’t really think about until you have to do it.

Ferguson eases the car out of the driveway and out on to the road. Sheldon, our escort driver, follows close behind. Other than the odd car, there’s not much for traffic tonight. Besides the engine, the only sound is the husband telling the wife how strange it feels to be driven around in their own car.

Part One: Dispatch

The idea for Operation Red Nose came in late September, 1984. A Quebec math professor and swim club coach was listening to a radio report about how a large percentage of fatal car crashes involved alcohol. That report, combined with stories from local bartenders, convinced him to start a service that would help keep impaired drivers off the road while raising money for his swim team.

The inaugural operation that December involved 25 swimmers, and turned into a major success after the Quebec City municipal police and a local radio station offered their support.

The service quickly spread across the country, arriving in Prince Albert for the first time roughly nine years ago. Like many other volunteers here tonight, myself included, dispatcher John Alexandersen is not a competitive swimmer. Still, after missing the first year in Prince Albert, he’s volunteered for every one since. Not just once or twice a year either. For the past eight years, he’s been here for every single night of Operation Red Nose.

“The phones could explode at any time,” Alexandersen says during a brief break. “We do what we can do. We do as many rides as we can handle.”

As with any service, everything begins with the dispatcher. When I walk in the door just after 9 p.m., other volunteers keep themselves busy by folding promotional pamphlets featuring a picture of Rudolph the Red Nose Reindeer with “Let Rudy take the Wheel” written underneath. Alexandersen, meanwhile, meticulously monitors the phone lines.

The majority of the calls are short and polite, but some are peculiar or downright strange. That’s no surprise considering the people who need Operation Red Nose the most have been drinking heavily.

The toughest part is filtering out all the talk to get two addresses. The first is where we meet the caller. The second is where we take them. It’s not easy. Sometimes directions include nothing but obscure or indecipherable landmarks like a friend’s house or a particular tree. The night before, someone called asking for Operation Red Nose to meet them at the “white house by the corner.” The caller couldn’t articulate which house or which corner. Another called and asked for a ride more than 50 km outside of Prince Albert. The soft-limit is 10.

“It depends on how many volunteers we have,” Alexandersen explains. “To go that far, it takes a team out of service for over an hour. If we had unlimited volunteers, maybe we could.”

Volunteer numbers are the most crucial part of the operation. Tonight, we have enough for five three-person teams, if everyone shows up as planned. If Operation Red Nose doesn’t get enough volunteers, then Alexandersen will have to start turning down callers. He hopes those people find cabs or friends to drive them home instead of the alternative. Fortunately, volunteer numbers are up this year, but the really busy periods, which begin at around 11 p.m., will test the organization’s efficiency.

“As the guy sitting here dispatching, it’s nice not to have to put people on hold,” he says. “Even still, the phone sometimes rings faster than we can deliver them.”

The phone rings a few minutes later. Alexandersen takes down all the information and enters it into a computer. Then he texts the two addresses to the two drivers and navigator making the next trip. This time it’s Team One, which includes veteran Operation Red Nose driver Nadine Moan, navigator and first-year volunteer Lasha Davidson, and longtime Lions Club member Jim Wilm. I’m just extra weight for this run. We all pile into an SUV donated by one of Prince Albert’s local car dealerships and head for our destination.

“You just do what you can to get them safely home,” Wilm explains as we pull on to Sixth Avenue West. “That’s the most important thing.”

This trip is fairly standard. There’s another house party in full swing, but someone has already started the car and two party-goers are quietly smoking on the front step. They call into the house as soon as we pull up, and we’re on our way in short order.

Wilm is driving another husband and wife home in their own vehicle, with Davidson serving as his navigator. Operation Red Nose guidelines call for two people to be present in a client’s car at all times, just in case something goes wrong. Typically nothing does. The worst memories anyone from Team One has involves getting puked on. That’s a small price to pay for taking a potential impaired driver off the road.

“I think maybe once I had someone a bit surly because they were so drunk,” Moan says as we follow Wilm and Davidson in the dealership car. “For the most part, they’re just so glad we’re there.”

Moan is a perfect fit for something like Operation Red Nose. A former taxicab driver, she left the business to study addictions counseling and later worked 26 years with the Saskatchewan Impaired Driver Treatment Centre.

Now retired, Moan sees this as an extension of her old job. She volunteers with Operation Red Nose every year.

“I still feel like I’m dedicating my life to ending impaired driving,” she says.

She also enjoys it. Moan is a self-described talker, who loves the chatter and the camaraderie that come with a position like this and vows to keep volunteering as long as she can.

“As long as I can physically do it,” she says when I ask her about it. “Just because I think it’s such a good cause.”

Moan sends a text back to dispatch as soon as we pull up to the client’s house. Wilm and Davidson get out and engaged in an animated, but friendly, discussion with the couple before Moan rolls down her window and yells “Merry Christmas.” The husband laughs and we’re on our way. That discussion is simply an extension of the one Wilm, Davidson and the outgoing couple had the whole trip.

“It’s the cab driver in me,” Moan chuckles. “Got to get to the next call.”

Part two: Donating to the cause

Moan may be a former taxi driver, but she’s adamant that Operation Red Nose isn’t a free taxi service. People who use it typically give a donation, but they aren’t required to. The money goes the Prince Albert Lions Club, who then distribute it to various clubs and organizations throughout the city. The most recent beneficiaries were a number of Prince Albert elementary schools. Moan says the fundraising aspect is one of the biggest reasons she keeps volunteering.

On this trip, the Wilm comes back to the SUV with a $20 bill. That’s about average for a donation. A few generous souls will leave upwards of $60 for a trip that only covers a few blocks, while a much, much smaller group of riders will not give anything at all.

Donations are a hot topic among volunteers, although most are loath to discuss it on the record. Some strongly object to picking up passengers who have a record of not donating for the trip. They say it’s taking money away from the various charities and non-profits the Lions Club supports. Others say giving them a free ride is better than the alternative. If that’s what it takes to keep an impaired driver off the road, they’ll sacrifice the $10 or $20 contribution.

“If they do donate, it’s a bonus,” says one volunteer who has lost two friends in two different impaired driving collisions.

My final trip as a navigator ends much the same way the night began. The husband and wife couple are talkative and friendly, and the trip ends with them thanking Ferguson for driving them home. This is the part where I switch to accountant, since all navigators are in charge of keeping track of the donations. The wife hands Ferguson a pair of $5 bills and he passes them on to me, then we join Sheldon back in the escort vehicle.

Operation Red Nose headquarters are almost deserted when we get back. Alexandersen is there, as are a couple of other volunteers who’ve just arrived. Plates of half-eaten fruit, muffins and pizza, donated by various restaurants around the city, are sitting on various tables. Team One has taken a brief supper break, only to be interrupted by a new call. When someone needs a ride, they don’t wait to finish their meal. They head out the door, and hope everything is still warm or fresh when they get back.

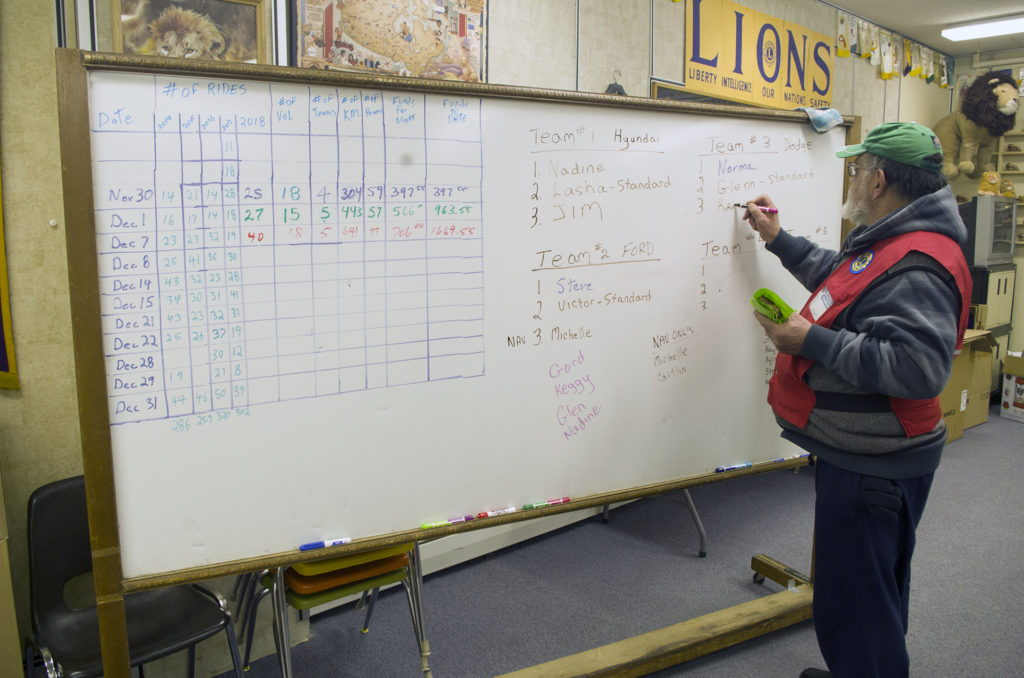

Longtime Operation Red Nose volunteer Stephen Denis is one of the few still waiting. As I take off my red Lions Club vest, he starts updating the giant whiteboard that contains a list of every team and every team member. “Jason Kerr – Daily Herald” is soon wiped off the board to make way for the new navigator taking over on Team Three.

Dispatch gets a call shortly thereafter and Denis prepares to head out the door. He’s one of the drivers on Team Two.

Team One arrives back home as he’s leaving, and various other volunteers begin to trickle in as midnight approaches. The office takes on a friendly, festive atmosphere as people tell jokes, compare stories, greet friends or dig into the midnight spread.

“You sure you don’t want to stay until 3 a.m.,” Operation Red Nose chair Randy Braaten jokes as I prepare to head out the door.

I laugh. Perhaps some day, although it won’t be tonight. The temperature sits at -15 C as I walk outside and head for my car. Meanwhile, Team Two pulls out of the parking lot and disappears into the cold, clear night.