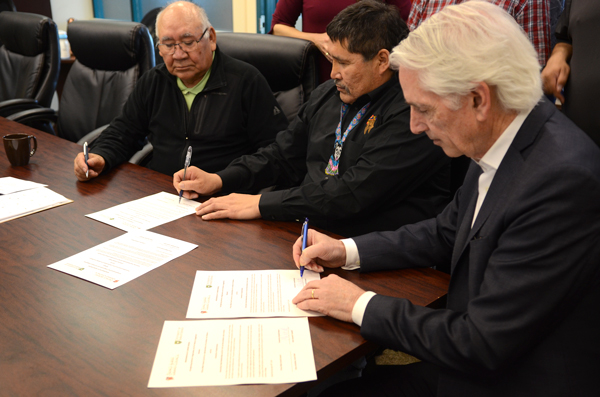

To Peter Stoicheff, the agreement signed at the Prince Albert Grand Council (PAGC) office Wednesday is more than just words on a page.

The University of Saskatchewan president visited Prince Albert to sign a memorandum of understanding with PAGC grand chief Brian Hardlotte and Senator Harry Cook and to take a first look at the future site of the Prince Albert campus. The agreement sets out a promise to ensure students coming from PAGC communities will be supported by the university, involved in the university’s Indigenization efforts and that the university will recognize and respect First Nations knowledge systems, worldviews, languages, ceremonies, values, ways of life and histories.

“A memorandum of understanding is only words,” Stoicheff said.

“But at the same time, it’s a public declaration of a set of commitments — not just a private one we know about, but one everybody knows about.”

Stoicheff said the agreement is bigger than the Prince Albert campus, which is set to open in the Forest Centre in the fall of 2020. In fact, he said that the MOU would exist with or without the Prince Albert campus.

“The University of Saskatchewan is not the University of Saskatoon,” he said. “It’s the University of Saskatchewan, for the whole province. It is particularly special, therefore, to be able to build a formal relationship that will become a deeply meaningful relationship with parts of the province other than Saskatoon. This, to me, is extremely significant, and the first time we have really done this. I thank you for this opportunity.”

Hardlotte was pleased the university and the PAGC had struck an agreement. He recounted the positive relationships the grand council had managed to build with other institutions, such as the Saskatchewan Indian Institute of Technology and First Nations University of Canada, which is associated with the University of Regina.

He mentioned programs such as dentistry, which used to be offered in Prince Albert, and will be returning to the new campus when it opens next year.

Hardlotte said news the university had bought the building and would turn it into a campus caught him off-guard, and the PAGC, originally, was disappointed. But through discussions with the U of S, Hardlotte said the PAGC became supportive of the university’s vision.

“I think this agreement will help shape a framework of dialogue, a sharing of information between the grand council and the university,” he said.

“We want to be involved. I think it’s going to support our First Nations students, and of course, the opportunity to strengthen our respectful relationship of the past.”

Hardlotte also said the MOU could serve to strengthen research in a way that supports the betterment of First Nations people.

“I think this agreement will establish networks of diverse expertise needed in the development of efforts of … communities to be collaborative, but also to emphasize research,” he said.

“Research is a very important area. We can definitely assist the university with the knowledge keepers we have, so I really emphasize that in this current agreement.”

While that research could cover several topics, Hardlotte specifically mentioned climate change as one area where interests of university researchers align with the PAGC’s.

The importance of relevant research also stuck out for Stoicheff. He spoke of the “importance of doing research with Indigenous communities, and the types of research they need, not just the research our researchers want to conduct.”

Agreement part of university’s commitment to bettering outcomes for Indigenous students

A major focus of the university right now is Indigenization and being a university with and for Indigenous people and communities, Stoicheff said.

“The university … has taken a long time to even understand the importance of being the best place it can possibly be for Indigenous students, communities and elders,” he said.

“I wouldn’t say by any means we are there. It’s going to take a long, long time, but we are committed to it. It’s part of our vision and part of our mission. The only way we can do it is by having Indigenous communities, Indigenous leaders, Indigenous knowledge keepers, language keepers and Indigenous students, faculty members and staff members helping the institution and us to understand how it can be the best place it can possibly be.”

Part of that is programming. Unlike other institutions, the university does not have a single, mandatory course on treaties or on Indigenous history, peoples or culture. Instead, each program must include Indigenous content tailored and authentic to its individual couses. That work, Stoicheff said, has begun.

He also pointed to what he called the “education gap.” About 23 per cent of Canadians has a university education. For Indigenous people, the percentage with a unviversity educationis about half of that.

That gap, he stated, has financial, quality of life and determinant of health costs to it. The financial cost in Saskatchewan alone has been pegged at more than $1 billion annually, he asserted.

According to Stoicheff, it’s why the university is in the later stages of building an Indigenous strategy, why it hired a vice-provost of Indigenous engagement and why the university is working to ensure graduation and employment rates for Indigenous students match those of non-Indigenous students.

“We take it very seriously that the university named after this province, the University of Saskatchewan, must be the right place with and for Indigenous students,” Stoicheff said.

“(Senator Murray Sinclair said) that education is the foundation of reconciliation. I think that’s foundational to what we are now doing.”