Michelle Gamage, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Tyee

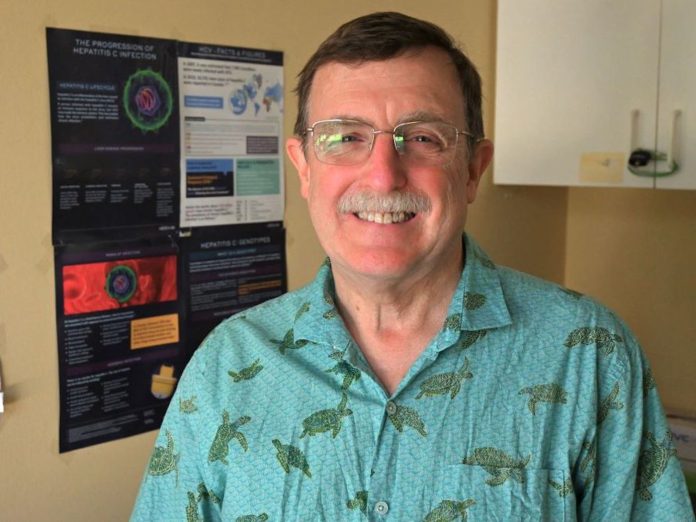

The hepatitis C Virus kills more people than most other communicable diseases, including AIDS and tuberculosis, says Dr. Brian Conway, medical director of the Vancouver Infectious Diseases Centre. Conway was recently named an Elimination Champion for his work fighting the disease.

This excludes COVID-19 which, as a generational pandemic gets measured differently by infectious disease experts, Conway adds.

HCV killed 290,000 people globally in 2019 according to the World Health Organization, including 1,162 Canadians.

Conway says between 200,000 to 210,000 people are infected in Canada and the provincial government estimates 16,000 British Columbians have chronic HCV infection.

The provincial government has signed on to the World Health Organization’s goal of eliminating HCV by 2030.

As of 2017, globally only 20 per cent of infected patients have been diagnosed and two per cent of all those infected are being treated, according to the CDA Foundation.

In Canada it’s closer to 30 per cent who don’t know they’re infected because they haven’t been tested, don’t think they’re at risk or don’t feel sick, Conway says.

Treatment for HCV is free under BC PharmaCare for people with Personal Health Numbers.

People who use drugs, people who have spent time in prison, Indigenous Peoples, men who have sex with men, immigrants from certain parts of the world and Baby Boomers are all populations at higher risk of HCV infections, according to Conway.

Over time, Conway adds, an HCV infection will cause liver failure. Patients can develop a swollen stomach, have difficulty thinking, bleed from their stomach and esophagus, develop rashes, be overly tired — which are symptoms of liver failure — or develop liver cancer.

“It can take decades to develop but you can look and feel perfectly well until your liver fails and you can be transmitting hepatitis C in the meantime,” Conway says.

HCV is a blood-borne disease so it can be transferred during intravenous drug use, sex or childbirth, Conway says. In other parts of the world people are infected when they receive unscreened blood transfusions or unsafe health care, according to the WHO.

Conway says Baby Boomers are at higher risk of HCV infections because many of them experimented with drugs or sex when they were younger and may not remember the incident that infected them, meaning they never get tested or seek treatment.

To treat HCV a patient has a choice of taking one of two direct-acting antiviral agents in pill form. Epclusa is taken once a day for 12 weeks and Maviret is three pills taken once a day for eight weeks. Both of these treatments have minor side effects and cure people 98 per cent of the time, Conway says. If those pills don’t work patients will be prescribed a second medication, Vosevi, which is 95 per cent effective.

“Put this all together and almost everyone gets cured eventually,” Conway says.

These medications have been fully covered by the BC PharmaCare program since 2018, according to the provincial government.

So why are infection rates still so high in B.C.?

That’s generally because people either don’t know they’re infected or hepatitis C is “nowhere near their top priority,” Conway says.

He’s been working in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood since 1998 and says engaging people in care is a huge part of getting people to start treatment.

“If there’s a guy whose been sleeping on the street, is using drugs and is thinking about eating a several day-old sandwich and I walk up to him and say, ‘you know what your problem is? You’ve got hepatitis C,’ I’m going to have zero credibility and he’s going to ignore me,” Conway says. “That doesn’t get him into treatment or cured.”

So Conway developed systems of outreach at community centres and, more recently, in housing projects to connect with people where they live.

“We meet with them to engage them in care and to provide them with HCV treatment within a multidisciplinary programme that helps meet all of their needs,” he says. The team also helps connect patients with housing, social programs, health care and addictions treatment.

For the past six years Conway says these systems of outreach have been getting 15 to 20 people into treatment per month. Ninety-eight per cent of people who start treatment go on to complete it, he adds.

Adding to this outreach Conway opened the Urban Health Centre at 219 Main Street this spring in partnership with Vancouver Infectious Disease Centre, the pharmacy SRx-Pier Health and Atira Housing.

Patients are welcome to walk in and an outreach team works in the neighbourhood to help find and connect with people who may need HCV treatment.

Since opening three months ago the clinic has enrolled 250 patients and started 16 people on HCV treatment.

Partnering with housing entities and the Public Health Agency of Canada means building managers and nurses giving people COVID-19 vaccinations can also flag patients who may have hepatitis C and need treatment, Conway adds.

He estimates over the last six years he’s cured between 2,500 to 3,000 patients of hepatitis C.

Treatment wasn’t always this easy. When Conway started work the existing HCV treatment took six to 12 months. Side effects included anemia, and making people feel like they were sick with the flu. The treatment worked 50 per cent of the time, Conway says.

The invention of direct-acting antiviral agents in 2015 revolutionized treatment and was “one of the most remarkable things that has happened in my career,” he says. “Treatment became dead easy.”

More work is being done to eliminate the virus from B.C.

On Monday the provincial government announced a partnership between the BC Centre for Disease Control, the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and the BC Hepatitis Network to create a made-in B.C. HCV-treatment and a hepatitis-elimination roadmap.

The province dedicated $105,000 towards creating the roadmap, which will define short-term targets for screening, treatment, engagement in care and community-based prevention and education, which the province says will be fully aligned with B.C.’s goal of eliminating HCV by 2030.

In 2018 the province tested 270,000 people for HCV.

Conway says he’d like to see every adult tested for hepatitis C once in their lifetime, like the U.S. is implementing. Germany also has a mandatory health check for every 35-year-old, where people are tested for hepatitis, diabetes and other health concerns.

“At minimum we should screen all populations who are at high risk,” he says.