Julia Peterson

Saskatoon StarPhoenix

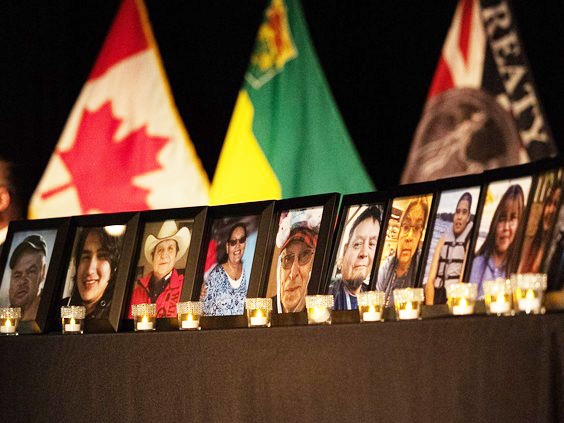

MELFORT — In the years before Myles Sanderson killed 11 people and injured 17 more in a stabbing spree at James Smith Cree Nation and Weldon, Sask. in September 2022, he served time in prison for assault, robbery, mischief and uttering threats.

His criminal record included 59 convictions and multiple violent offences.

“Unfortunately … it would not be unusual to see a criminal record like this,” said Cindy Gee, Correctional Services of Canada (CSC) district director for Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba.

In 2021, he was released to serve the remainder of his sentence in the community, which is also a normal process, Gee told an ongoing public inquest into the mass stabbing.

In most cases, CSC strongly prefers to do a “gradual release,” rather than keeping someone behind bars as long as possible, she said.

“When an offender has been in a federal prison, and they’re finally getting out into the community, you can imagine how exciting that would be — you’re getting out of prison, right? But there are a lot of factors to consider. If someone is detained until the end of their sentence, and they get out on warrant expiry, they’re gone. … There’s no one checking on them. There’s no one making sure that they’re not using (drugs); there’s no one checking in with their family to make sure that they’re not drinking.”

People who are released before warrant expiry — on day parole, full parole or statutory release — are still under CSC jurisdiction, and have to follow a set of rules and conditions. These can include no-contact orders with various people, regular check-ins with a parole officer, abstaining from intoxicants and regularly accessing mental health supports.

If someone breaks those rules, they become ‘unlawfully at large,’ which is “basically the same as escaping from prison,” and a warrant will be issued for their arrest, Gee said.

And on the day of the mass stabbings, Sanderson was unlawfully at large, having breached his release conditions multiple times. According to Linda Flahr, supervisor of Saskatoon parole for CSC, parole officers believe that his first breach of conditions was purposefully deceitful, while the second was likely accidental. In both those cases, he was released back into the community.

After the third time he breached his conditions, he disappeared off CSC’s radar completely until Sept. 4, 2022.

“There was nothing in his file, in the discussions I had with my parole officers, in the circumstances … that would ever have led us to believe that this was a possibility,” said Flahr.

“I HAD CONCERNS,” PAROLE OFFICER SAYS

Jessica Diks, who served as Sanderson’s parole officer when he was an inmate at Saskatchewan Penitentiary, said he “changed significantly” over the time she worked with him.

“In my initial interactions with him, he was extremely guarded and adversarial, accusatory,” Diks recalled. “He presented as somebody who was quite angry and felt he had been very hard-done-by by the system, and notably so.”

On top of that, just as he was starting a program meant to help him build skills and make changes in his life, COVID-19 arrived.

“That was an enormous struggle for everybody, and in this case was particularly problematic,” Diks testified. “It reinforced the issues and beliefs Mr. Sanderson had, regarding being mistreated within the system. … He had committed to working within his program (and) was making strides, but through no fault of his own, was unable to proceed or move forward in this case. That was very frustrating for him.”

Conversations she wanted to have with him about where he would go and what he would do once released were “also significantly interrupted by COVID,” Diks said.

When they did talk, he often told her that he wanted to live with Vanessa Burns, his common-law spouse, and return to James Smith Cree Nation.

“I had concerns with that, because there was a significant history of domestic violence,” Diks said.

Nevertheless, over the years of his incarceration, he got involved in various programs at the prison and “did make significant change,” she said.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

“(He) became much more engaged with both myself … and other institutional workers.”

As Sanderson’s institutional parole officer, Diks was responsible for writing reports about his risk factors and making recommendations about whether or not he should be released on parole.

Diks said he had many risk factors, including the length and violence of his criminal history.

She said she recalls thinking, “This guy still needs a lot of help. He needs support, maybe additional programming.”

With all that information in mind, she recommended he be denied parole on multiple occasions.

Looking back at Sanderson’s time at Saskatchewan Penitentiary, Diks told the inquest she believes everything was done by the book.

“From an institutional perspective, I don’t know that there’s anything that could have been done differently.”

“WE NEED TO GET OUR STORY OUT THERE”

As the inquest continues, some members of James Smith Cree Nation’s health and wellness teams have expressed frustration that the jury isn’t hearing about their work, and about the supportive resources within the community.

JSCN family wellness worker Cindy Ghostkeeper-Whitehead said she voluntarily took “a lot of significant training” over a 10-year period prior to Sept. 4, 2022 — suicide intervention, first aid, mental health first aid, debriefing and intervening in family violence — to better help friends, neighbours and loved ones on the First Nation.

Ghostkeeper-Whitehead and her team told reporters they worked closely with the Melfort RCMP during those years.

“They would phone us at our office, and they would say, ‘Can you go do a wellness check on so-and-so?’ And we would go and do that wellness check,” she recalled.

In the aftermath of the stabbings, the wellness workers became “very, very cautious” and security workers have now taken over responding to many of the calls that used to be the wellness team’s responsibility, she said.

Still, the team’s work continued.

“After Sept. 4, we worked hard on making sure that the families got what they needed; unfortunately, we had experience in this,” said Ghostkeeper-Whitehead. “We’ve had a few other tragic happenings here, and so we did gain some experience in how to help the families.”

Listening to testimony at the inquest — particularly about resources to help the community and what can be done to prevent a future tragedy — JSCN community health director Mike Marion said the lack of discussion about what his own community has to offer has been glaring.

“We have people in place,” he said. “We have the emergency response team; we have the crisis response team. We have first-aid members that are there and trained, and could support during an emergency that happened in our community. We work together with the external agencies …

“(But) they’re not hearing our side of the story, what we have in place in our community. They’re presenting all the support services that they have externally, but they’re not looking internally at what we have in the community.”

One major goal of the inquest is to come up with recommendations for the future. Marion said he wants to make sure the hard work already being done by JSCN members doesn’t get lost in the shuffle.

“We need to get our story out there and get it out to the public (that) we’re there,” he said. “We’re there to support.”

If you or someone you know is in immediate danger of self-harm or experiencing suicidal thoughts, please contact Crisis Services Canada (1-833-456-4566), Saskatoon Mobile Crisis (306-933-6200), Prince Albert Mobile Crisis Unit (306-764-1011), Regina Mobile Crisis Services (306-525-5333) or the Hope for Wellness Help Line, which provides culturally competent crisis intervention counselling support for Indigenous peoples (1-855-242-3310).