Warning: This story contains details that can be upsetting to readers

The remains of 215 children located at the site of a former residential school set up to assimilate Indigenous youth hit home for the community of Lac La Ronge — where families gathered at the site of the former All Saints Indian Residential School for a ceremony honouring victims and survivors on June 4.

“It has brought us together but it’s a really difficult time right now just coming to the realization that these 215 children didn’t make it home,” Lac La Ronge Indian Band Chief Tammy Cook Searson said.

“I hope that we’re able to come together even more now and to have more action for our communities. I know that there are more unmarked graves and children that didn’t make it home from residential school.”

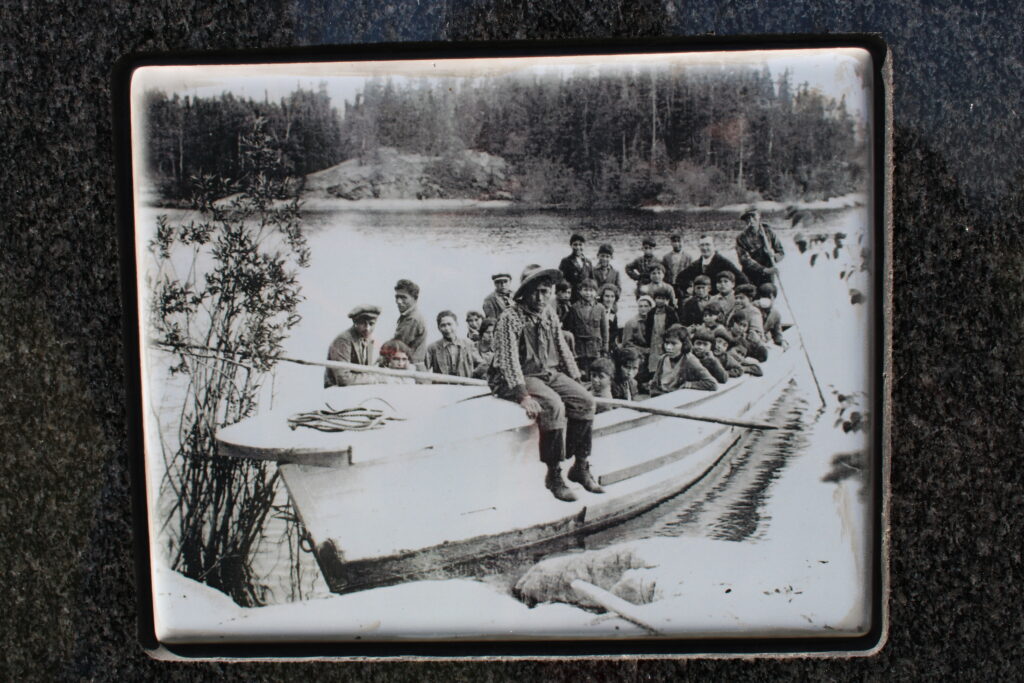

The All Saints Indian Residential School was run by the Anglican Church of Canada. The school opened in 1907 after the closure of a day school that had been in operation since 1889. It ran until 1947 when it was destroyed by fire. After that children were shipped further south to Prince Albert.

Across Canada the residential school system separated at least 150,000 Indigenous children from their families — until the last one closed its doors in 1996.

Cook-Searson, who went to residential school in Prince Albert, said the same ground penetrating radar technology that located the mass grave in B.C. will be used to search a graveyard beside where the Lac La Ronge school once stood.

“My grandparents went here and many of us here are connected with our families going to the school here,” Cook-Searson said.

“It’s going to be a difficult process but it’s something that we have to go through as a community together. It’s going to be really, really hard.”

Residential school survivor Tom Roberts said a lot of work needs to be done to prepare the community for the difficult work of exploring the old graveyard.

“A terrible thing happened, not only in Kamloops, right across Canada. The moms and dads, grandmothers and grandfathers, didn’t get to see their children or grandchildren. Some of them don’t even know where their grandchildren are buried. Some don’t even know how their grandchildren died. This is just the tip of the iceberg,” Roberts said.

“There are children buried back there who died at the residential school right here on the ground where we are sitting. Children died of malnutrition, children died of pneumonia, children died of measles or smallpox.”

Roberts said that when a child died at a residential school, the families would not know until the following year because they only had contact with their children for two months in the summer.

“How sad that must have been for the mom and dad if their child didn’t come home. There’s over 4,000 children that they counted that died in residential schools in Canada. There’s over 6,000 and counting of children that went missing in Canada — and those numbers are growing,” Roberts said.

“We know there’s something back there. There’s graves back there. I know for a fact we will find some here at the graveyard in La Ronge and I’m not ready for it — I’m not prepared for it. We’re going to do some counselling work and therapy work before anything is dug up back here. Hopefully by then I’ll be ready.”

Cook-Searson said that her experience at residential school left her self-esteem shattered and that it took a long time for her to be able to share her story and begin to heal.

“I too went to residential school when I was seven years old with my late sister, she (died by) suicide in 2003. In Prince Albert we were so lonely,” Cook-Searson said.

“We weren’t allowed to sleep together in the same bed… but my sister would always let me sleep with her and then she would move me before we would get checked on in the mornings. I’m so glad that we had each other there. But it’s such a painful time.”

Cook-Searson said a combination of fear and shame long kept survivors quiet about the abuse that they suffered while at the schools. The children who died at Kamloops, she said, never had a voice in life but are speaking loudly now.

“We didn’t know what our parents went through or what our grandparents went through until the residential school settlement agreement came and then we started talking,” Cook-Searson said.

“We started talking about our experiences and we started talking about the impacts of what happened in residential school but it took us a while because our voices were suppressed and oppressed. We were scared of being punished, we were scared of what might happen — and so many things have happened to us. We each have our own story.”

In order to heal she said those stories need to be brought to light. She said the legacy of what happened at the schools has led to serious mental health issues, addiction and crime in the community.

“I was actually sexually abused by one of the workers at the residential school and I never talked about that. I didn’t tell anybody. I didn’t say anything because it was something that you just didn’t talk about. I didn’t even tell my mom and dad,” Cook-Searson said.

“It took me a long time to come out with that and to say something because I was keeping it inside. I thought it was me and I blamed myself for a long time… But I think we need to start sharing our stories and to start sharing the pain that we went through because our communities are suffering — our communities need help.”

Roberts said his time in Prince Albert pulled him away from his family, although his brother was at the same school they were not allowed to speak with each other.

“Life was different. No mom. No dad. It was sad because when we left here with our siblings we were talking all the way to Prince Albert sitting together and talking Cree. When we got to Prince Albert we were separated. You can’t talk to your sister or brother or you get a spanking. My goodness, they were our brothers and sisters,” Roberts said.

“What happened later in years was the kids we went to school with, sat with, went to bed with at the residential school, they became our brothers.”

Roberts said an Elder gave him good advice for his healing journey — to be patient because it doesn’t happen overnight.

“In order to heal you must go back in time and find out what happened, why it happened and where it happened,” Roberts said.

“Once we can figure that out and understand that then the healing can begin — and you don’t just heal like that in three months — you work on yourself. It’s a lifetime of healing.”

Christopher Merasty, who founded the Men of the North support group for men in the community, organized a sacred fire from Monday to Friday that culminated in launching 215 miniature birch bark canoes into Lac La Ronge.

The canoes were launched from the same place where children bound for the residential school in La Ronge would disembark.

“The healing process is such a need in our communities throughout Saskatchewan… Creating that awareness and starting that healing process is definitely something that is needed not only in our community but in communities throughout Canada,” Merasty said.

“Men of the North deals with men and mental health, helping through intergenerational trauma and abuse — I myself am a sexual abuse survivor. We help support them to create that awareness so that way they can start healing those wounds and healing from those past intergenerational trauma experiences.”

Lac La Ronge Indian Band councillor Linda Charles of Stanley Mission also spoke at the ceremony. She said families that were torn apart by the residential school system are still healing.

“All of those children that went there and never made it home, or the ones that came back but had to endure the suffering that was done — all the harm that was done. We remember them and we continue to pray for them,” Charles said.

Cook-Searson said community members need to be strong and supportive of one another through this difficult time as these wounds are made fresh. Maintaining that network of support will help people through the hard reckoning that is happening now.

“I know that I’ve come a long way… It took a long time to have self esteem and to be confident and to be able to be here today,” Cook-Searson said.

“Reach out to each other. No matter who you are and no matter what you’re going through don’t ever give up. Just keep supporting each other. It’s been a really hard history that we’ve come through. The children are speaking loudly and it’s an awakening for all of us. We have so much more work to do. That’s what we have to do is to come together and to find a way forward.”

Cook-Searson launched a birchbark canoe into Lac La Ronge and pushed it out onto the water, in the opposite direction of the boats that brought children from around the north to that dark place.

“What a powerful way to heal and to come together — to honour and to recognize the 215 lives that are speaking so loud — that have woken us up.”

A national 24-hour Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available to support survivors and those affected. You can access emotional and crisis support referral services by calling 1-866-925-4419.