Trillian Reynoldson

Regina Leader-Post

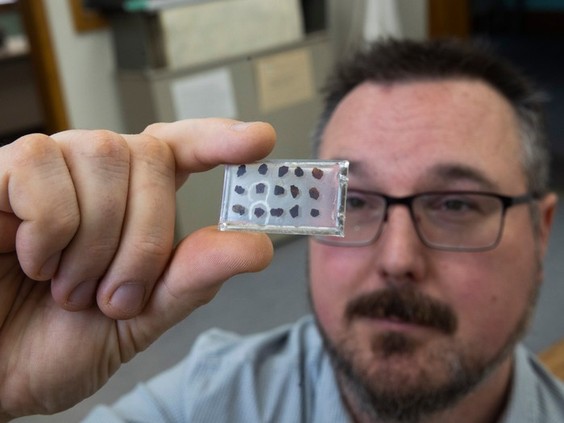

Ryan McKellar, curator of palaeontology for the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, says a new major discovery provides the opportunity to look back in time — around a million years before dinosaurs went extinct.

After leading a research team made up of graduate students and curatorial assistant Elyssa Loewen for around five years, McKellar is excited their work has led to the discovery of the first amber deposit in the province to have insects preserved in it.

“It’s important for palaeontologists or people who are interested in fossil insects because it helps fill in this gap in the fossil records that we’re unsure about 78 million years ago up to about 50 million years ago,” he said during an interview Wednesday.

According to McKeller, the new fossil records are closer than ever before to sampling a diverse set of insects near the extinction event, helping researches fill in a 17-million-year gap in insect fossil records.

McKeller said the amber deposit — which was found in the Big Muddy Badlands — was formed around 67 million years ago, preserving insects that lived around a million years before the extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs. He added there aren’t many deposits from that time period, meaning there isn’t a lot of information on insects.

The research team took an interest in the Big Muddy Badlands because the rocks are around the right age to look at the end of the Cretaceous period, which began 145 million years ago and ended 66 million years ago with the extinction of the dinosaurs. McKeller said the rock layers that recorded the extinction event are exposed in places like the Big Muddy Badlands, around Shaunavon and Grasslands National Park.

“It looks like we’re seeing a change in the groups of insects that are in this deposit compared to older deposits from the Cretaceous in places like Alberta,” he said, adding that deposits found in Alberta, Europe and Asia tend to contain insects that are characteristic of the Cretaceous.

“The cool part about Big Muddy amber is that we’re not seeing these groups of insects. Instead, we’re seeing groups of insects that tend to have modern relatives. They basically replaced some of these really characteristic Cretaceous insect groups with groups that we’re familiar with today.”

McKeller uses a three-pronged approach to study amber, which means his lab will look at it from three points of view.

They will look at the chemistry of the amber, comparing the fossil resin to modern resin in order to determine which group of trees produced the deposits. They will also look at the amber’s geochemistry to determine which types of carbon and hydrogen it’s composed of, and they will look at the insects trapped inside of the amber.

McKeller believes the preserved insects found in Big Muddy are more closely related to modern insects due to the rise in flowering plants at that time. While the plants were fairly new around 125 million years ago, he said they became more widespread by the end of the Cretaceous period and started taking over for cone bearing plants.

The research, which was featured in the scientific journal Current Biology, shows an insect turnover might have helped set the stage for the extinction of the dinosaurs.

McKeller also worked on an international team that discovered three new species of ants that didn’t survive past the Cretaceous period in North Carolina amber formed around 77 million years ago. “It allows us to see that somewhere between North Carolina amber forming about 77 million years ago and Big Muddy amber forming about 67 million years ago, there’s a really big change that happened in the insects in North America and it seems to be showing up in places like Asia as well.”