Prince Albert police have one main message to the public when it comes to missing persons: “Any information is good information.”

Sept. 13 to 19 marks Missing Persons Week in Saskatchewan. The province currently has 133 historical missing persons, with Prince Albert investigators tasked with nine of those and one unsolved homicide.

However, according to Sgt. Darren Androsoff, Prince Albert police have received 410 missing person reports so far this year. That averages out to about 45 a month, and over one a day.

He said some are repeats, who often run away from group homes or are involved with gangs or addictions: “They need help surviving day-to-day.”

Regardless, he said, all missing person files are equally important and the impacts on loved ones is just as difficult.

Androsoff, a member of the Police and Crisis Team and formerly of major crimes, said dispatchers will first get key information such as the missing person’s name, age, where they were last seen and a clothing description.

The person will be evaluated as low, medium or high risk, and then the case will be handed off to a police officer.

The officer will investigate from there, which includes looking into the person’s social media or speaking with others who may have information on their common daily activities.

“We’re trying to learn as much about their life as possible in as short amount of time as possible,” said Androsoff.

“Every piece of information is a little puzzle piece,” he said, asking anyone who knows something about a case to report it, no matter how small or insignificant it may seem.

Sgt. Kathy Edwardsen investigates historical missing person cases, also known as cold cases. June Johnson is the oldest case, she said, dating back to 1979.

“As a police agency, we’re looking for justice and we’re looking for closure for the families,” she said.

But that closure isn’t just for loved ones––If foul play is involved, coming forward as the person responsible will bring you closure, too.

“Yeah, there’s going to be consequences; however, holding a huge secret like that and hiding and lying your whole life, it’s not healthy and the only way you can have healthy relationships is being honest with the people in your life,” said Edwardsen.

“No case is ever closed unless we have the truth, so there’s no closing it in a box and putting it on a shelf.”

One of the biggest challenges with historical cases is people passing away.

Edwardsen said it’s common for investigators to interview people more than once. Over time, people tend to get more comfortable releasing something new.

That new information can lead investigators in a new direction or to a different person to speak with.

Mikayla Worth, Missing Persons Liaison with the Victims Services Unit, said loved ones usually face “emotional whiplash.”

Family or friends are dealing with constant reminders of the missing person. This could include things like birthdays or anniversaries, or more unexpected triggers like walking past someone who’s wearing a similar jacket the missing person always wore.

Worth frequently used the term ‘ambiguous loss,’ which is a loss that occurs without closure or understanding.

“It will start almost right away and it still continues even after an individual is located, it can still continue for a little bit and it comes in waves,” she said.

“It’s emotionally exhausting for the families.”

Anxiety surrounding the missing person can interfere with the loved one’s self care, such as not being able to sleep or eat.

Worth said families often “have a hard time sitting back.” They’re typically quite active on their social media raising awareness that the person is missing, or busy hosting campaigns or walks.

“We’re all on the same team and we want the same thing at the end of the day,” said Worth.

“We want answers.”

Worth emphasized that you don’t have to wait 24 hours to report a missing person and you don’t have to be a direct family member. You can also report to a jurisdiction outside of where the person was last seen, and the information will be forwarded to the appropriate jurisdiction.

The Missing Persons Database on the Saskatchewan Association of Chiefs of Police (SACP) website shows 133 missing persons in the province, nine found unidentified human remains and 29 located persons.

Statistics show 96 missing persons, or 72.2 per cent, are male and 37, or 27.8 per cent, are female. Seventy-one are listed as Caucasian, two visible minority and 60 of Aboriginal descent.

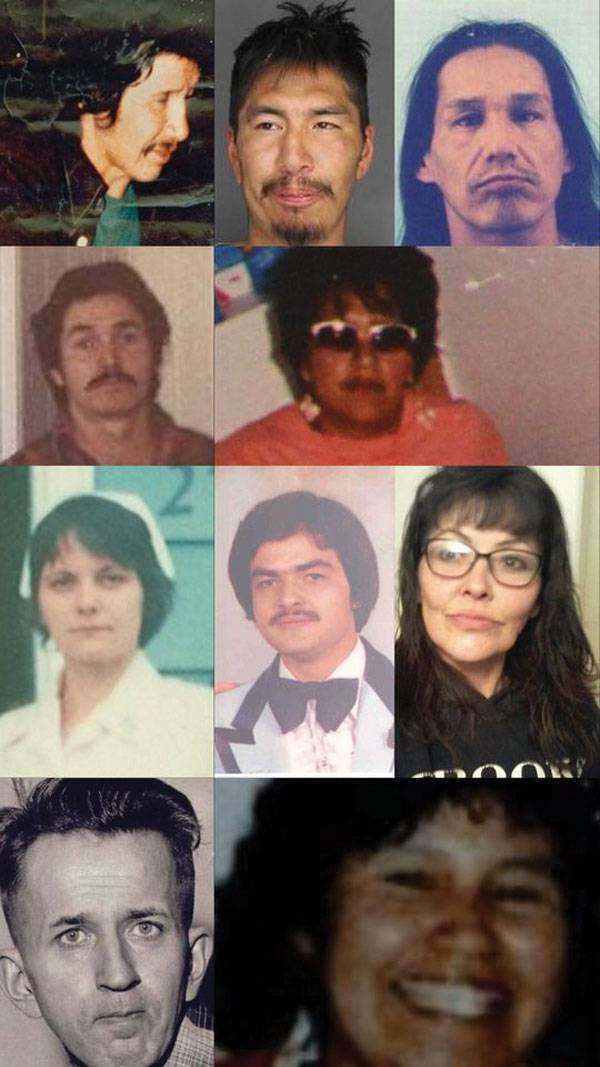

Below is a list of historical cases of missing people last seen in Prince Albert, according to SACP:

- June Johnson — Last seen Aug. 3, 1979

- Robert Wiggins — Last seen Jul. 28, 1980

- Joseph Couldwell — Last seen May 25, 1981

- William Slywka — Last seen Nov. 7, 1982

- Samuel LaChance — Last seen Jul. 29, 1987

- Ernestine Kasyon — Last seen Dec. 6, 1989

- Norman Halkett — Last seen Mar. 16, 2003

- Timothy Charlette — Last seen Oct. 8, 2014

- Happy Charles — Last seen Apr. 3, 2017

Edwardsen said police are still investigating the murder of Jean LaChance, who was killed in 1991.