by Julia Peterson

Saskatoon StarPhoenix

Warning: This story contains disturbing details and descriptions of violence some readers may find upsetting.

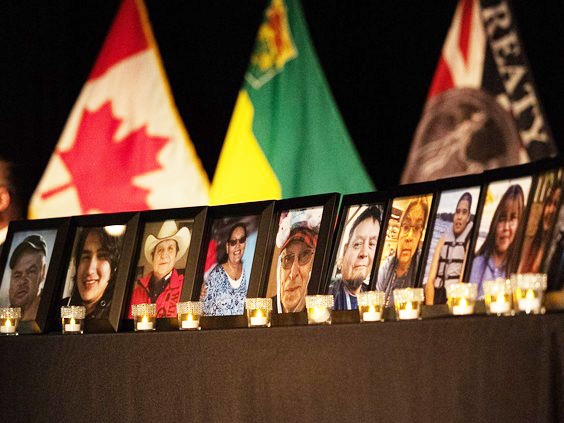

MELFORT — The second week of the coroner’s inquest into the 2022 mass killings on James Smith Cree Nation and in Weldon is underway.

The first week of the inquest wrapped up with testimony from an RCMP profiler who said Sanderson had a list of grievances and was ready to kill anyone who got in his way. The inquest has heard he had a history of violence and incarceration, including 59 convictions as an adult. He was unlawfully at large at the time of the killings.

A second inquest focusing on his death in police custody is scheduled for next month.

Criminal investigative psychologist Matt Logan told the inquest Sanderson had many psychopathic traits.

Logan never met Sanderson and said he can’t make an official diagnosis; he relied on court and prison records, as well as discussions with community members.

He described Sanderson as having an unstable and abusive childhood, noting he struggled with alcohol addiction and used methamphetamine and cocaine.

His common-law partner, Vanessa Burns, testified about 14 years of domestic violence by the father of her five children. The inquest heard Sanderson attacked her on multiple occasions, including when she was pregnant.

An RCMP overview said Sanderson went to the First Nation to sell cocaine and was causing chaos there with his brother Damien Sanderson in the days before the killings.

Damien was the first to be killed. Staff Sgt. Carl Sesely, an RCMP criminal profiler, said Myles killed him because he got in his way.

Myles then went door to door, stabbing and killing people. Sesely said some were targeted because Sanderson believed they were associated with a gang while others got in the way of his “mission.”

Family members of the victims said the inquest has been difficult. Deborah Burns, whose father Earl Burns Sr. was among those killed, said it has been exhausting but it’s important to hear the information.

“I feel like I am getting some answers to my questions,” she said on Friday.

‘Very efficient’ EMS response

After the stabbing spree started that morning, the first 911 call came in at 5:44 AM.

Only 17 seconds later — only about as long as it takes most people to tie a shoelace — an ambulance was getting ready to respond; less than 10 minutes later, it was on the road.

That morning, 10 emergency medical services (EMS) crews went to James Smith Cree Nation. Ambulances came from Melfort, Tisdale, Nipawin and Prince Albert, followed by Saskatchewan’s entire three-helicopter STARS Air Ambulance fleet.

Sherri Jule, EMS director for the north zone of Saskatchewan, said paramedics decided to set up and treat almost all of their patients at the band office on JSCN — rather than going out into the community to respond to calls for help — as a matter of safety, and because of how many people had been hurt.

“In the beginning, there weren’t a lot of paramedics on scene yet, so they had to make a decision to move to the band office and have people come to them so they were able to see all the patients in a timely manner,” she said.

At the band office, as medics treated, triaged and colour-coded their patients — green for minor injuries, yellow for more serious injuries that could wait for further care, red for patients in critical condition — a conservation officer armed with a carbine rifle stood guard.

“(Paramedics) were concerned about their safety en route, not knowing what to expect,” said Jule, summarizing what she’d heard from first responders after the fact. “But once things were set up at the band office and the triage was organized and coordinated, policing had a strong presence.

“Once they saw that policing was there to support them, they felt safe.”

Hospitals all over the province prepared to receive the wounded — sometimes in groups of two or three, as ambulances took multiple patients at the same time — and before 9 a.m., the final ambulance was on the road.

Every injured patient who got treatment that morning survived; the deceased never even made it to the triage centre.

“I truly believe that we had a very efficient response,” Jule told the inquest. “I can’t identify any improvements.

“From previous mass casualty incidents, we learned a lot. I believe this incident identified our learnings, and the success of our learnings from other ones.”

‘Code Orange’

Carrie Dornstauder was the SHA director on call on Sept. 4.

That morning, hospitals in Melfort, Nipawin, Prince Albert and Saskatoon received an influx of patients from James Smith Cree Nation, some in critical condition.

Shortly after 9 a.m., Dornstauder oversaw a “code orange” being formally called for the northern and Saskatoon-based hospital system.

This meant that non-critical patients could be moved elsewhere to make space, and more staff would be called in.

“In this case, night staff stayed over to support the day staff, and day staff came in early,” Dornstauder said.

The hospitals also prepared for family members of the injured patients to call with questions about their condition — or even which hospital they’d been taken to — and added staff to handle the phone lines.

Each hospital also made space for families to gather, and brought in Elders and social workers.

As coroner’s counsel Timothy Hawryluk noted, the first time many people in Saskatchewan would have heard about a code orange was after the Humboldt Broncos bus crash. While some Saskatchewan hospitals have used that code since then, none involved as many patients and one were as high-profile as this.

“It … brings a lot of coordinated effort,” said Dornstauder. “It is extraordinary. It indicates that a large volume of patients are expected to be coming our way.”

‘We’ve had nothing to this scale before’

The mass killings were also a trial by fire for Saskatchewan’s fledgling system of organizing peace officers throughout the province.

In 2018, the province created a Protection and Response Team (PRT), allowing conservation and highway patrol officers to assist the RCMP and municipal police in responding to crimes.

Since these officers either train at the Saskatchewan police college or get separate training that meets police standards, they carry weapons including pistols and rifles; conservation officers also have shotguns.

In April 2022, Saskatchewan brought many of its law enforcement agencies — including conservation, highway patrol and prisoner transport officers — into the same structure, the Provincial Protective Services (PPS) branch of the Ministry of Corrections, Policing and Public Safety.

Less than six months later, the RCMP called on the provincial team for help at James Smith Cree Nation.

Over the following days, 53 PPS officers were involved.

Sgt. Alex Heron, a peace officer working for PPS, told the inquest these officers were tasked with clearing buildings, securing crime scenes, providing hospital security and following up on potential suspect sightings.

“We’ve had nothing to this scale before,” Heron said of the team’s response.

PRT officers don’t normally do hospital security, but as the situation was evolving, it was important to limit access to the hospital, preserve as much evidence as possible, and be prepared to protect the survivors in case Myles Sanderson came back, he said.

Officers from the Melfort area also offered their local knowledge — particularly the conservation officers, who were especially familiar with the back roads and ATV trails.

Other officers did roving patrols and searched farm houses and outbuildings. One single officer, Heron said, personally cleared and checked more 50 crime scenes on James Smith Cree Nation.

Additional investigation

Last week, RCMP Staff Sgt. Robin Zentner told the inquest that the first 911 call about the stabbings came in shortly before 6 a.m. on Sept. 4.

Later in the week, Damien’s wife Skye Sanderson testified that she made multiple 911 calls earlier that morning, before the stabbings began, using a friend’s phone.

She said her father, Christian Head, who was also killed that day, had asked her to bring a gun to his house that morning.

In light of her testimony, over the weekend Zentner and his team checked their records. After going back over the RCMP’s audio recordings and transcripts from interviews with Skye Sanderson, Zentner said she never mentioned these early 911 calls during the investigation.

Sask 911 staff were also asked to check their records for any calls coming from James Smith Cree Nation on Sept. 3 and 4, 2022, as well as any calls from Skye Sanderson’s phone, the other number she said she had called from, and any other phone numbers associated with her friend.

Shortly before the inquest resumed on Monday, Zentner said Sask 911 had told him “there were no phone calls made to Sask 911 … from any of those phone numbers” during that time period that the RCMP did not already know about.

Zentner said every time someone calls 911 in Saskatchewan and asks for help from an RCMP detachment, the RCMP will create a file about that call “right at that moment.”

Melfort RCMP received 22 complaints — opening 22 new files — between midnight on Sept. 3 and shortly before 6 a.m. on Sept. 4, 2022, the inquest heard.

Other than Skye Sanderson’s call in the early hours of Sept. 3, the day before the stabbings — which both she and multiple RCMP members spoke about last week, and in which she reported that her husband Damien had stolen her vehicle — “not one of those complaints is associated with Myles Sanderson, Damien Sanderson, Skye Sanderson … or linked to the phone number Skye gave us,” Zentner said.

Christian Head’s phone records also showed no outgoing calls that morning, and none of the texts he sent referred to a gun, a firearm, or ‘buddy,’ which was what Skye said her father had called the gun.

— With Canadian Press files