Content warning: this story includes discussions about sexual assault and murder

On a summer day in August of 2016 Colten Boushie, a young Indigenous man, was shot in the back of the head by Gerald Stanley after entering his farm with his friends. The trial against Stanley was emotionally charged and the acquittal of Stanley shocked one part of the nation, while another part celebrated on Stanley’s behalf.

The acquittal broke any hope the Boushie had left in Canada’s criminal justice system.

From this trial came a documentary; nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up

Award-winning filmmaker Tasha Hubbard followed the trial and its aftermath with a crew and unveiled bias in the justice system. Hubbard also looked at the history of violence against Indigenous people, and their erasure from the systems of law and power, to the present day, exposing the need for systemic changes.

Although the family was shocked and saddened from the acquittal, they and their community continued to stand up for Colten Boushie and for a better future for the generations to come. The family met with the Prime Minister and spoke with the U.N about bias in the justice system in front of the international community.

The trial and acquittal started a discussion of systemic racism within the justice system and within the country.

Dr. Verna St. Denis, an Indigenous scholar and U of S professor, speaks about racism in the education system and about critical race theory.

“Critical race theory has five or six principles or tenets.” St. Denis explains. “One of them is that racism is endemic in all systems. So, the legal system, the education system, the political system. In that sense, critical race theory is a way that acknowledges that racism is an issue. It would take a case like the murder of Colten Boushie and the trial of the defendant as racism operating in that system.”

There were 12 jurors selected for the trial against Gerald Stanley. One Indigenous man was denied as a juror without a reason given. The selected jury was all white.

In the film, Hubbard states that no juror was asked if they are biased against Indigenous people.

“Another tenet is that whiteness is an advantaged identity.” St. Denis says. “That’s what the film is illustrating. How whiteness is seen as neutral, objective, innocent. Even in the midst of blatant murder. There’s still benefit of a doubt. It was called an accident, which is really a stretch. But yet, the defense lawyers were able to convince a jury, ostensibly an all-white jury, that this was a credible defense.”

In the trial Gerald Stanley claimed that the gun went off accidentally while he leaned over Colten Boushie to turn the SUV off and take the keys out of the ignition. Stanley claimed that he had the gun in his right hand and he turned the ignition with his left hand.

The argument of whether or not it would be possible to lean over a person with a gun in the right hand and turn the ignition off was not questioned during the trial, however some people who tried to re-enact the manoeuvre and said it would not have been possible.

After Boushie had been shot, the RCMP were called, but Boushie’s body, along with the vehicle, were left overnight, uncovered. It happened to rain that night and crucial evidence was washed away.

The RCMP went to Boushie’s mother’s house and told her that her son was deceased. They then questioned her, despite her having been nowhere near the scene when the incident took place.

The witnesses were also questioned and while they took the stand during the trial, they claim they felt like they were the ones on trial instead of Stanley.

The film shows alleged mistakes and negligence of RCMP officers and also looks at racism towards Indigenous people throughout history. From intentional starvation, to treaties that were not fully understood, to the displacement of reserves and how Indigenous people were no longer allowed to hire lawyers.

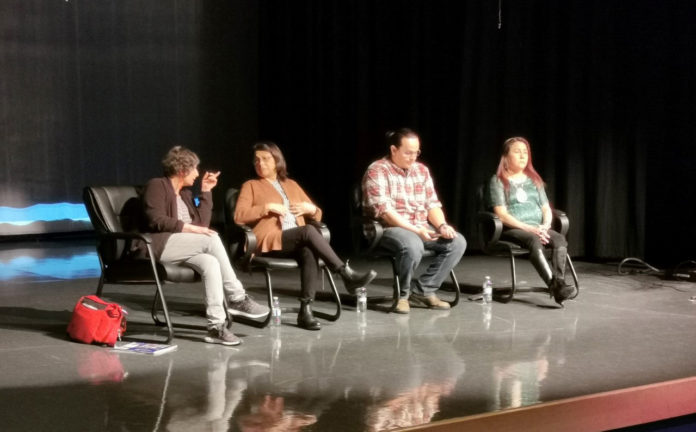

In a discussion panel after screening the film in La Ronge, St. Denis compared the Murder of Colten Boushie to the murder of Pamela George.

“I was thinking back to the murder of Pamela George,” says St. Denis.

“A 28-year-old Indigenous woman who was brutally raped and murdered by two white men in Regina in 1996 and then the resulting trial and then the resulting sentencing of those two men.”

Two white men beat Pamela George to death and her body was left on the road of the outskirts of Regina. During this trial the fact that George was occasionally a sex worker was heavily relied on by the defense and is why the two men received charges of manslaughter and not murder or sexual assault.

“And then I was thinking of the sexual assault and rape of a 12-year-old First Nations (girl) out of Tisdale by three young white men,” said St. Denis.

“When I listen to that trial, that’s going back now 20 years, I was shocked and dismayed at the inability of what I felt the prosecutor to defend that young girl and also the way I which the media represented and reported on that case in particular. Both the legal system and the media collaborate to basically undermine the identity, the humanity, and the human rights of Indigenous people.”

Because the girl grew up in an abusive home, the defense on the case for this young girl suggested that she was the sexual aggressor and out of three men, only one was convicted with a conditional sentence and no jail time.

“There are a lot of changes that need to happen and I believe in education,” St. Denis says.

“Last week I was invited by a few faculty to the College of Law at the University of Saskatchewan and they wanted to consult with me and my colleague, Dr. Sheelah McLean, to discuss how to introduce a course in anti-racism, a required course in law education. And this is in 2020, that the law school is finally considering a course in anti-racism. And what I learned at that meeting is there is just one other college in the Country that has just recently introduced a course in anti-racism. So, I think that’s part of the message that comes out of the film here. That we do need education and it’s not just education for Indigenous people, but education for us all.”

York University, located in Toronto, states that, “Students will consider how advocates have worked to bring claims of racism to the courts. The class will assess the extent to which courts have addressed or failed to consider claims of racism, whether systemic or individual, in their interpretation of various areas of criminal law. How has recognition of this particular piece of “social context” been integrated into judicial decision-making and criminal procedure?

Students will study key parts of the criminal trial process from start to finish including bail, jury selection, Charter and common law motions, and sentencing.” in the anti-racism course that they now offer.

Before the trial against Gerald Stanley, mainstream media focused on Colten Boushie’s life and character, as though he were the perpetrator and not the victim.

It was assumed that he was an addict and had a police record. But people who knew him claimed that he was nice, did well in school, cut firewood for elders, and helped out at ceremonies.

Stanley’s life and character was neither examined nor questioned. It was assumed that he was a hard worker with no criminal background or addictions of any kind. No one asked Stanley, his family, or friends if he had shown violence in his past.

Property laws in Saskatchewan became stricter after a survey where 65 per cent of people wanted harsher penalties following Boushie’s death.

Many people took to social media to congratulate Stanley and to say they would have done the same thing. A councillor by the name of Ben Kautz wrote, “His only mistake was leaving three witnesses,” on a Saskatchewan farmer’s facebook page, which is now closed.

Colten Boushie’s family had filed for an appeal on Stanley’s acquittal, which was denied by the Crown as there is, “no legal basis.”