A northern Saskatchewan First Nation is bridging the gap between cultural identity, art and technology with a project aimed at inspiring the next generation to continue reclaiming and preserving their Indigenous language.

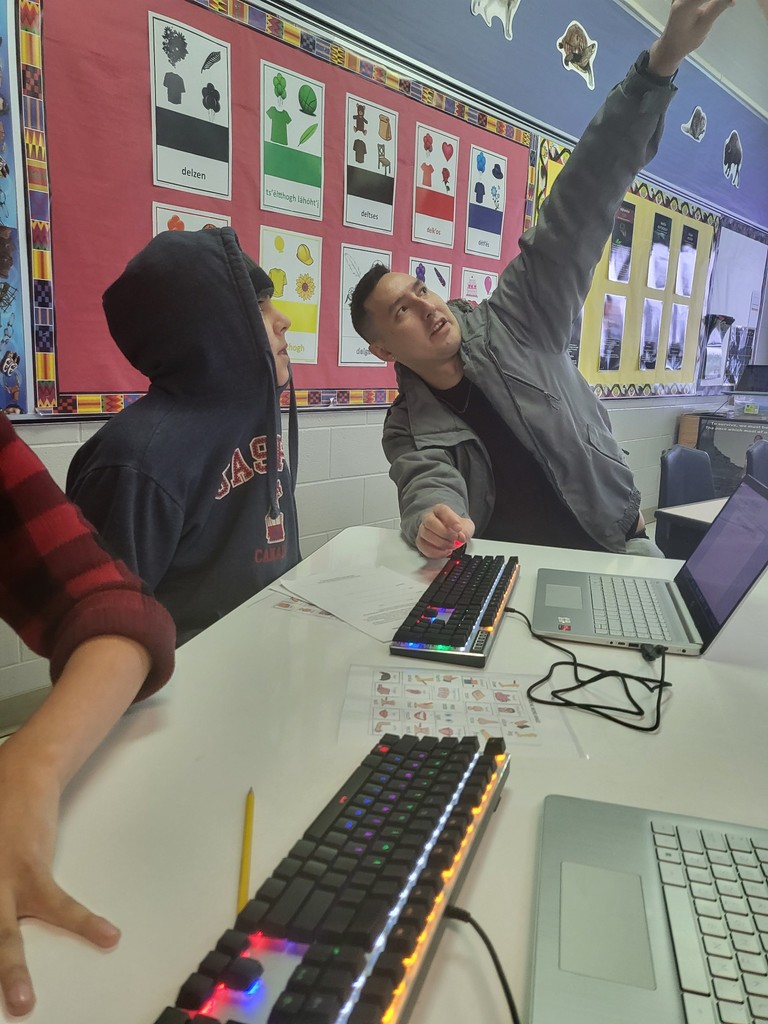

As part of a collaboration with Common Weal Community Arts, the world’s first Dene language computer keyboards were recently unveiled at the St. Louis school in Patuanak, English River First Nation, approximately 400 kilometers north of Prince Albert.

“When I first got the keyboard, my eyes lit up like Christmas lights; I was so amazed,” said Dene language specialist and retired St. Louis School teacher Carol Estralshenen. “The keyboard lights up and the kids, they were really interested in that. They think that’s a cool gadget that they have and once they start typing, they have smiles.”

With the guidance of Dene elders and Estralshenen, Denesuline keyboard developer Chevez Ezaneh designed the keyboards with youth in mind.

“One of the things that I noticed was lacking in schools and stuff was that we didn’t have any computer keyboards in Dene. There were ways to type it before, but nothing visual,” said Ezaneh. “Everyone that’s trying to type their languages on a computer, they’re using an English language keyboard and so, I had to figure out how to develop that.”

Almost completely self-funded, Ezaneh worked on the keyboards on and off over the past couple of years, but as he got older, he started to realize how valuable time really is.

“Bridging the gap between language and technology is an important step for my people if they are to preserve their cultural identity going forward into the modern world,” he said. “Whenever I say something in my language, it’s a direct connection to the past, to my ancestors. Not having your language means not having that connection to your cultural identity.”

With the success of his Dene language keyboards, Ezaneh’s goal is to develop a keyboard for every Indigenous language in Saskatchewan within the next year.

“That’s where I want to start and then continue on for all the other languages in Canada, maybe more,” he said. “I know that indigenous languages are facing various challenges throughout the world. It’s not just something that’s localized here.”

Estralshenen said before receiving the keyboard from Ezaneh, it would take her close to five minutes to type a single word. Now, it takes her less than a minute to write a complete sentence.

Ezaneh’s Indigenous Keyboard Project is part of the Northern Languages Program, which was first established in 2022 and led by Ezaneh’s mother, artist Michèle Mackasey, with the help of Elders, Language Keepers and other community members in northern Saskatchewan.

During a three-year long residency with Common Weal in Patuanak, Mackasey created a commemorative portrait of two local youth who died in a house fire out of message-filled bottles with the help of the community.

“Then it just sort of came to me [that] I really wanted to do a project involving language with youth and sort of bring it in through doing these bottle pieces,” she said.

While Mackasey’s projects can be complex, Estralshenen said the students have really enjoyed being involved.

“It’s a learning process for the students, the children,” she said. “A lot of learning, a lot of asking, a lot of curiosity.”

Mackasey’s next piece for the Northern Languages Program involves collecting words in Dene and Cree from Patuanak youth and engraving them onto glass vials to arrange into a portrait of a young girl who died at the Beavual Residential School.

“I used to go stop by at the school and I had been walked through the graveyard. That graveyard always really captivated me,” Mackasey recalled of her trips to Patuanak and Beavual in the early 1990s. “I would see these little, tiny crosses and it was kind of weird because I knew there was a school fire and there were some lives lost then, [but] I knew there was something more there.”

While looking through archival images with Estralshenen, Mackasey was drawn to a black and white photo of a girl wearing a school uniform with her arms crossed on top of a desk.

“It was in a classroom full of kids, but she was the clearest one in the photo and the look on her face was very striking,” said Mackasey. “I showed the photo to Carol and all of a sudden, she broke out into a story… It turns out, this is somebody from Patuanak who died from medical neglect.”

Mackasey asked her if using the photo would send a message about the residential school legacy, and Estralshenen confirmed it would.

“Imagine [it] full of messages that are written in Dene and Cree by youth, by new generations, when you’re recognizing a child from the past that had her language taken from her and didn’t even make it,” said Mackasey. “We’re trying to tell a story and entice youth at the same time.”

Mackasey was born in northern Quebec but grew up in Ontario and attended Francophone schools until grade four. She said she shocked to find out that children learning the French language is both encouraged and funded by the Government of Canada.

“Why is it that you have these Indigenous languages that don’t have the same opportunities? It’s really shameful,” noted Mackasey. “If there weren’t those [residential] schools, these kids would still be speaking their languages.”