Three years ago, Harold Johnson was on a flight coming back from Wollaston Lake.

The Crown prosecutor was sharing a flight with Dale McFee, the former Prince Albert police chief and then deputy minister of justice.

They were returning from a day of circuit court in the north. Johnson was trying cases. At the back of the makeshift courtroom, probation officers were checking in with their clients. McFee was observing that process. On the flight back, he turned to Johnson.

He said they had 45 people on probation. Of those 44 said they had problems with alcohol. The 45th was a 12-year-old boy with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder.

McFee asked Johnson what they should do.

Johnson was already growing disillusioned with how the justice system handled alcohol.

He asked for six months off to help change the story around alcohol.

He hasn’t been back in the prosecutor’s office since.

Johnson and three others began to travel around the north talking to people about alcohol. They didn’t have anyone to answer to. They went out to work in and for communities.

The Northern Alcohol Strategy was born.

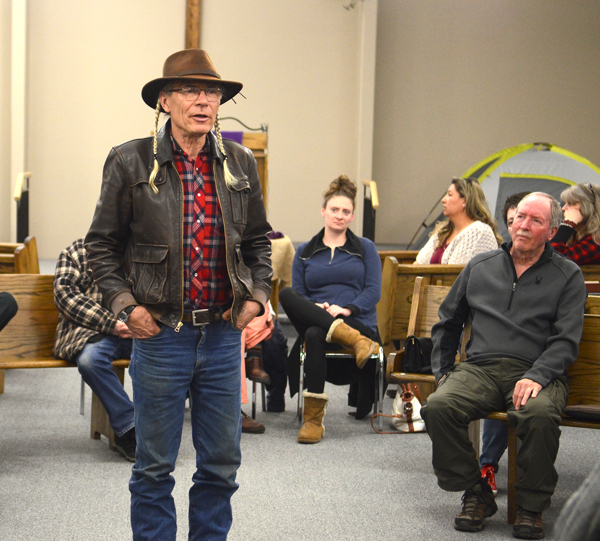

Thursday, Johnson spoke to dozens of people crowded into one half of the Grace Mennonite Church. NDP MLA Nicole Rancourt was there, as were both candidates for the Prince Albert Carlton NDP nomination.

Two city councillors were also in attendance — Coun. Evert Botha and Dennis Nowoselsky.

Others included a student from Wesmor School and members of Grace Mennonite Church.

They listened intently as Johnson talked about the conversation he has been having for the last three years.

Some of those conversations he has detailed in his acclaimed book, Firewater: How Alcohol is killing my people (and yours).

Those conversations include the four models we use to deal with alcohol – criminal, health, victim and trauma.

He was particularly critical of the victim model.

“The victim story … is destroying us,” he said.

It’s making it worse.”

He said he has heard those concerns — that alcoholism is a result of residential schools, or colonialization and of poverty.

As a lawyer, though, he knew that questions are more powerful than statements.

So he asked people: “Do you drink because you are poor, or are you poor because you drink?”

Then he leaves it there.

Those questions, he said, are powerful enough on their own.

“We had a hard go,” he said.

“Residential schools were a bitch. That can’t be our story. We can’t be victims.”

He then took aim at the drunken Indian stereotype.

“That lazy, dirty, drunken Indian stor7y, that’s a lie,” he said.

First Nations people are lawyers, doctors, judges, business people — they’re not dirty drunks.

The percentage of sober First Nations is twice that of Canadians as a whole.

Still, Johnson said, he hears the story of the dirty, lazy, drunken Indian.

He then turned his sights on the trauma model.

He estimated that the prosecution’s office handles 11,000 northern files a year. Each of those files has multiple traumas. With a population of 30-40,000, it doesn’t take long for one population to be traumatized multiple times.

‘Alcohol is an effective medicine for PTSD. The problem is the side effects. Before long, it kills you,” Johnson said.

“We’ve got this wheel of trauma and grief and drinking and trauma and grief and drinking and trauma and grief and drinking. The only thing I can think to knock out is the alcohol spoke.”

***

Johnson said through his conversations, people remember when alcohol became a problem in their northern communities

In the 1940s and 50s, he said, there was some drinking sometimes.

But in the 1960s, when the miners came to town, the smoke jumpers came to town and the wealthier American tourists came to town, they would party seven days a week. They only invited Aboriginal women.

“Everyone remembers that was the first time they saw hard liquor,” he said.

He paused for a moment.

“This shit continued on my watch.”

Johnson said he contributed to the problem when he was younger, but now, he’s sober.

His goal is to encourage other people to understand the alcohol story and start the conversations that lead to change.

In 2016, after urging from Dr. James Ermine, Johnson and the Northern Alcohol Strategy set up a study. They looked at emergency room visits with alcohol involved, days alcohol sales increased, and days the number of alcohol-related calls for service increased.

They all spiked around the same days — paydays, family allowance days and welfare days.

The day before those days, they saw something else. School attendance numbers would drop.

‘(Students) know stuff is coming. They start to tense up,” he said.

They looked at the numbers again in 2017. They were up slightly. But then, for the first time, people were writing them down. Alcohol as a factor wasn’t anything they had thought about before that.

It was just a regular part of life.

In 2018, they weren’t able to do the survey.

But this year, they’ve started collecting the numbers, and they are way down. ER visits related to alcohol are down. RCMP calls related to alcohol are down.

‘”It’s changing,” he said. “It’s getting better.”

What changed in those years is how the story of alcohol was told. The strategy continued to get up and talk to whomever they could. They lobbied the Town of La Ronge to restrict the hours off-sale liquor was available. They began to examine the possibility of a managed alcohol program.

Mostly, though, they talked to people.

And they didn’t do it alone.

***

Harold Johnson’s brother Gary was killed by a drunk driver and sentenced to three years in prison.

Johnson spoke on behalf of his family at the sentencing hearing, to make sure the judge knew who that impaired driver took away.

‘When the sentence was passed, Gary didn’t come back,” Johnson said.

But the driver was shamed. And his kids and grandkids were shamed.

“That three-year sentence didn’t do anyone any good,” Johnson said.

That demand for punishment, that reliance on deterrence in the justice system, doesn’t work.

Johnson met with the man who had killed his brother, and he said he wanted to go into schools and talk about drinking, to tell students how it feels to wake up one morning and learn you’ve killed someone, but have no memory of the night before.

So they did.

They stood side-by-side, shoulder-to-shoulder, in Churchill High School in La Ronge. Johnson spoke about what it was to lose someone. The driver spoke about what it was to take someone away.

‘He’s earning his redemption,” Johnson said.

“The justice system doesn’t do that.”

They began to have that conversation.

That conversation is the same one Johnson tried to get going in Prince Albert Thursday night.

Between stories, observations, and honest comments on the effects of alcohol, he answered questions and spoke about policy.

Increased availability is going to increase harm, he told one guest.

But banning alcohol outright will increase harm too. The sweet spot is in the middle.

He praised the efforts of the Wesmor students who have worked to launch the sober house initiative in Prince Albert.

Mostly, though, he tried to pass on a message of hope.

‘We’re winning,” he said.

“We can do this. It’s hard, but it’s really good too.”

Saskatchewan is behind on this, he said. Other provinces have alcohol strategies and are doing what they can to change the conversation.

The theme I’m talking about is changing the story we tell ourselves about alcohol because it is just a story. It’s not even our story,” he said.

“It was a story that was given to us and it’s a story that is dominated by the industry through advertising. Take back our stories and shape them to become stories that work for us. We do that through conversation.”

Despite his stories, his words, his thoughts and his observations, that’s not what Johnson hopes people take away from his Thursday night visit.

“How many people are there in Prince Albert?” he asked.

“I could never talk to all of them. But I could get these guys inspired to talk, and they’ll go to their relatives and their friends, and the conversation will permeate through the community.

“That’s where the change happens. That’s how we change the story.”