Warning: This story contains details that can be upsetting to readers

The Lac La Ronge Indian Band began a search for unmarked graves at a cemetery on the site of two former residential schools in downtown La Ronge on Thursday.

The search is being led by survivors of the schools. Elders and support-workers will be present throughout to offer support and guidance in the community. Ceremonies began on Thursday with the lighting of a sacred fire and will conclude with a community feast on Monday.

“We started cleaning up in the cemetery just over three weeks ago… It looks really beautiful,” Cook Searson said. “We ask for people’s prayers. For guidance and for strength.”

Cook-Searson said people stopped by the cemetery as it was being prepared by Elder Tom Sanderson, to talk with him about their oral histories of people who might be buried there.

“As they were cleaning people stopped in and shared their own histories and recollections of what they were told,” Cook Searson said. “It’s bringing up a lot and we want to make sure that everybody is heard, and everybody has a voice.”

Cook-Searson said it’s important for people to support each other during this time. She thanked the mayors of adjacent setter communities and the local Anglican Church for being supportive.

“I really appreciate that. Having that support and helping us through and just being there with us helping us out,” Cook-Searson said.

“Bishop Adam Halkett will be there. We also have a pipe ceremony. We’re being inclusive and also being very respectful. It’s difficult work, but it has to be done.”

The search is prompted by recent investigations into unmarked grave sites at former residential schools around Canada that have yielded devastating results.

Cook-Searson said she had advice from Cowessess First Nation Chief Cadmus Delorme, who is leading his community through the recognition of 751 unmarked graves in that community.

Like in Cowessess, oral histories in Lac La Ronge say there are unmarked graves outside the confines of the cemetery.

“Before, if people weren’t baptized, they were buried just outside of the cemetery. We asked our contractor to clean up around the cemetery, where the fence is. So, we’ll be able to do the ground radar search just outside the cemetery,” Cook-Searson said.

“We’ve also had other sites that have been identified by community members, so that’s something to work on. But for now, for this weekend, we’ll focus on this site where the two residential schools stood.”

Across Canada the residential school system separated at least 150,000 Indigenous children from their families — until the last one closed its doors in 1996.

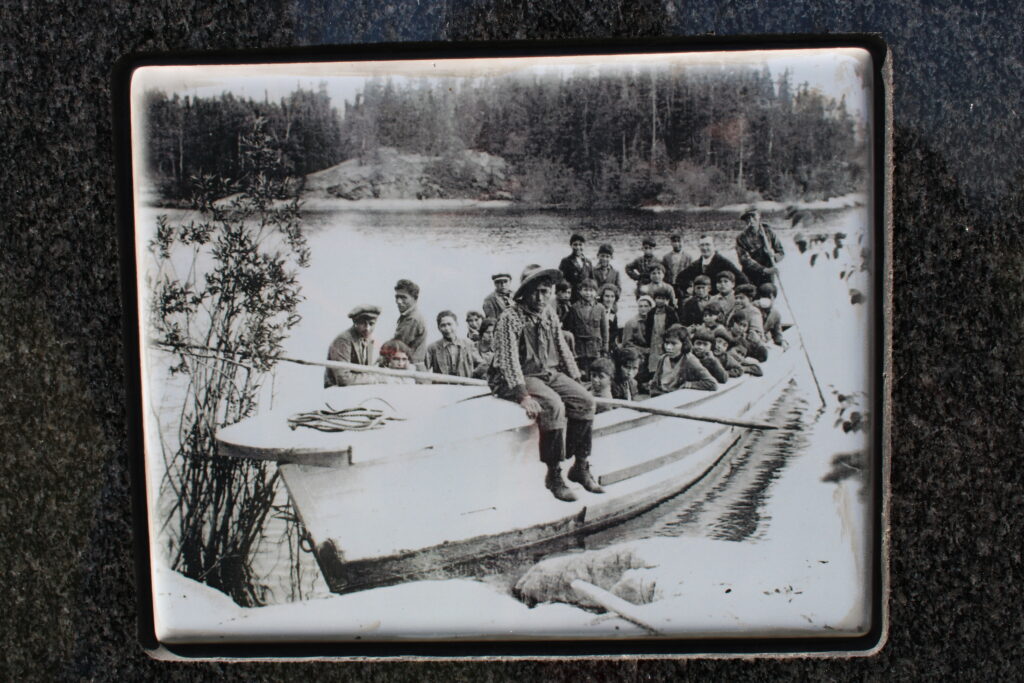

The All Saints Indian Residential School was run by the Anglican Church of Canada from 1907 after the closure of a day school that had been in operation since 1889. It burned down in the 1920s and a second school was built that shut its doors in 1947 after two boys set it ablaze. After that, children were shipped further south to Prince Albert and Punnichy.

The adjacent cemetery was used by the community until a new one was built. The site is now part of the First Nation’s urban reserve.

“It’s a cemetery that has unmarked graves. We don’t know how many,” Cook-Searson said. “I think it’s important for us to get the work done in light of having a residential school in our community for 40 years.”

After this weekend she said crews from SNC-Lavalin, who are doing the ground-penetrating work, will be able to determine further steps.

She said everyone in the community is welcome to attend the ceremonies and show their support.

“There are going to be a lot of people there this weekend… It’s important for us to come together.”

A national 24-hour Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available to support survivors and those affected. You can access emotional and crisis support referral services by calling 1-866-925-4419.