This is the eighteenth in a series of columns about the 70 British Home Children sent to St. Patrick’s Catholic Orphanage in Prince Albert between 1901 and 1907. While all orphanage records were destroyed in the terrible fire of 1947, every attempt has been made to trace the life stories of these dispossessed children through genealogy websites and newspaper databases

John William Chester: Son of an Unwed Mother

The 1889 British Poor Law (Amendment) Act “allowed local authorities to assume parental rights and duties with respect to children in their care. …. Furthermore, in 1889 ‘desertion’ [of a child] was held to include cases where a parent was imprisoned under a sentence of penal servitude or was imprisoned in respect of an offence committed against the child. … [This legislation] helped organizations retain children without their parents’ wishes and therefore more easily arrange for their emigration.” – Roy Parker, Uprooted; The Shipment of Poor Children to Canada, 1867-1917 (2010)

The mother of John William Chester (1889 -1947), Mary J. Chester (1869-1923), a single mother and cotton mill worker at Skipton, Yorkshire, was imprisoned for three months in 1901 for neglecting her 12-month-old baby, one of William’s younger siblings. The British census for 1901 shows Mary in His Majesty’s Prison at Armley, a foreboding, castle-like jail, perched prominently above Leeds, Yorkshire.

Mary’s oldest child William, born in Skipton the son of an anonymous cotton mill hand, was sent to live with his mother’s older brother William Chester and family at Skipton while she was incarcerated. Two years later, William was shipped off to Canada at 13 years of age to take up residence at St. Patrick’s Catholic Orphanage in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

When William was an infant, Mary Chester had a job and some support from her family. For example, Mary’s mother Nancy Chester was present at William’s birth at their home in Skipton on 9 October 1889. The 1891 census shows 22-year-old Mary living with her mother Nancy, her stepfather John Whittaker, her brother William, and her 1-year-old son John William in Skipton. Mary and her brother were working as cotton weavers in a local mill.

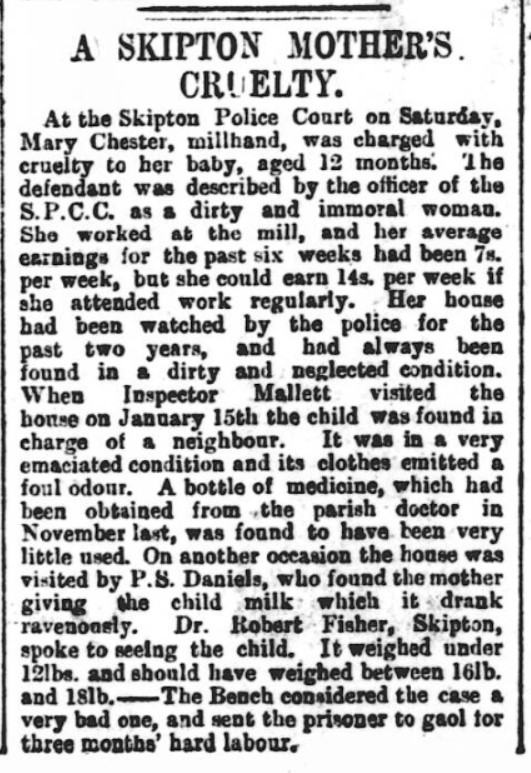

On 30 January 1901, the Burnley Gazette’s report of Mary’s appearance in Skipton Police Court on the charge of child neglect states that, as an employee at the cotton mill, “her average earnings for the past six weeks had been 7s per week, but she could earn 14s per week if she attended work regularly.”

Newspaper accounts of Mary’s trial describe her as a “dirty and immoral woman,” stating that her home was in a “dirty and neglected condition.” The baby which she was accused of neglecting was “in a very emaciated condition and its clothes emitted a foul odor.” Dr. Robert Fisher of Skipton saw the infant and reported that it weighed 12 pounds when it should have weighed between 16 and 18 pounds.

I was shocked by these accounts so I did some research into social conditions in England during the Industrial Revolution. Since the New Poor Law of 1834, British women were declared the sole financial supporters of their illegitimate children. Yet these women had few resources and little power.

“Victorian authorities assumed a successful mother stayed home,” Ginger Frost writes in her 2008 article “Motherhood on Trial: Violence and Unwed Mothers in Victorian England.” “Any mother who left her children for hours every day failed in her duty, even if she was trying to earn enough money to buy food.” Most notably, Frost points out, “the Victorian obsession with dirt and filth comes through clearly in the [child] neglect cases. As scholars have shown, middle-class writers associated dirtiness with sexual impurity, disease, and general moral laxity. … Unwashed children covered with vermin were the ultimate sign of degeneration.” Yet, for Mary and thousands of unwed mothers like her (between 1860 and 1890, 30,000 to 40,000 illegitimate infants were born each year in England and Wales), avoiding starvation trumped cleanliness. Nevertheless, mothers like Mary were jailed for neglect without any thought to providing economic reforms that might improve their lives.

The newspaper stories about Mary Chester even make her appear negligent for leaving her baby with a neighbour, likely so she could go to work at the cotton mill. So what did the court do? Sentenced her to three months’ hard labour. Mary was not a bad person. She was a victim of a cruel economic system that had no social safety nets, as was her son William.

“William said he was getting into trouble in England and his mother was having a hard time like so many other families,” his granddaughter Lorraine Chester of Prince Albert wrote to me on 9 January 2023. “She [his mother] felt he would have a chance for a better life if he came to Canada.” After his stay with his uncle, William ended up at the Salesian School in Battersea. Founded by St. John Bosco (Don Bosco), the Catholic order aimed to provide educational opportunities for poor boys. The Salesians were also involved in the British child migration scheme, and it wasn’t long before William was sent overseas.

William arrived at the Prince Albert orphanage in the spring of 1903. The 1906 census for the prairie provinces records him there at age 14 (he would have been closer to 17). As he was one of the older boys, he was expected to work under the supervision of Brother Courbis on the orphanage farm near White Star. Courbis helped William apply for a homestead in the Buckland area.

William married Marie Colvez, a local girl, in 1914. By 1916, according to the census for that year, the couple were farming at 50-26-W2 with their two young sons William (1) and Eugene (1 month). They had six more children after that for a total of five boys and three girls.

Lorraine Chester informed me that in 1920 her grandparents William and Marie paid to bring his mother Mary and his siblings Alice and Ernest over from England. Mary only lived for three years after she arrived and is buried in the White Star cemetery. In 1924 or 1925, William traded his farm for a house in Prince Albert and went to work, first for the Gilmore Ice Company, then for Burns meat packing plant, and finally at Sic’s Brewery where he worked until his death in 1947. His wife Marie died in 1976. They are both buried in South Hill Cemetery in Prince Albert.