Elder Liz Settee knows the importance of connecting to one’s culture.

The Prince Albert elder and active community supporter is known in Prince Albert for helping others to connect to theirs. It’s become her life passion. She’s always teaching.

“I can’t say it’s one culture fits all. I’m not saying my way is the right way,” Settee said.

“This is the way I was taught. These are the teachings that were given to me. Even with the powwow, many young people — it’ something in them. They want to learn.”

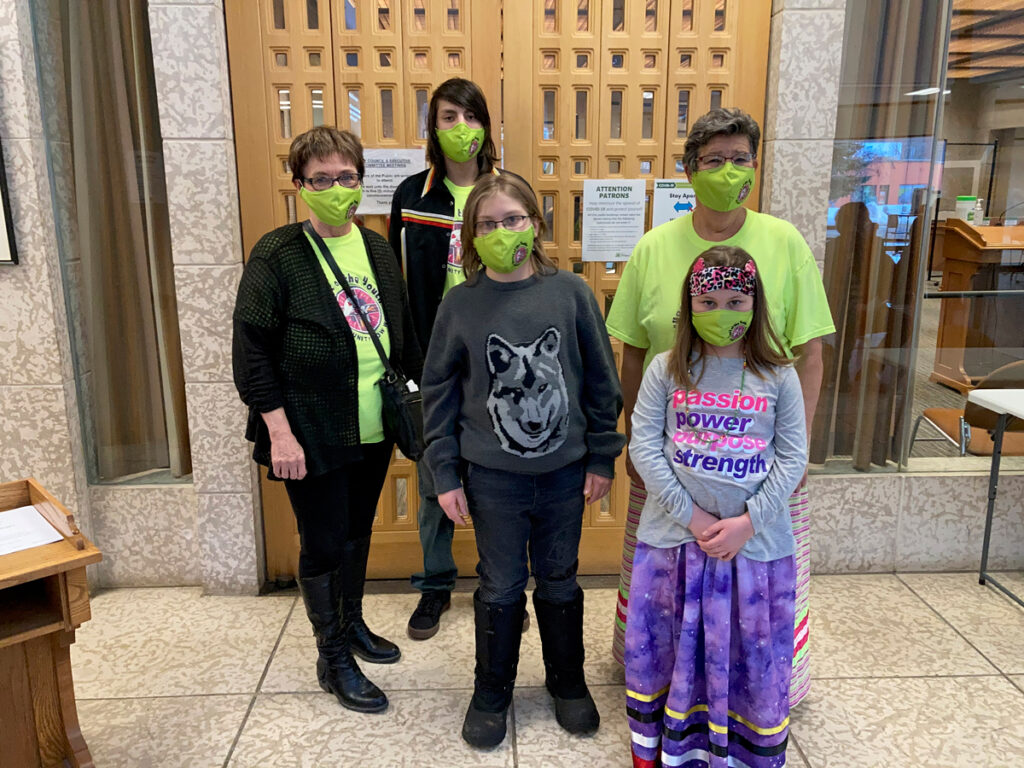

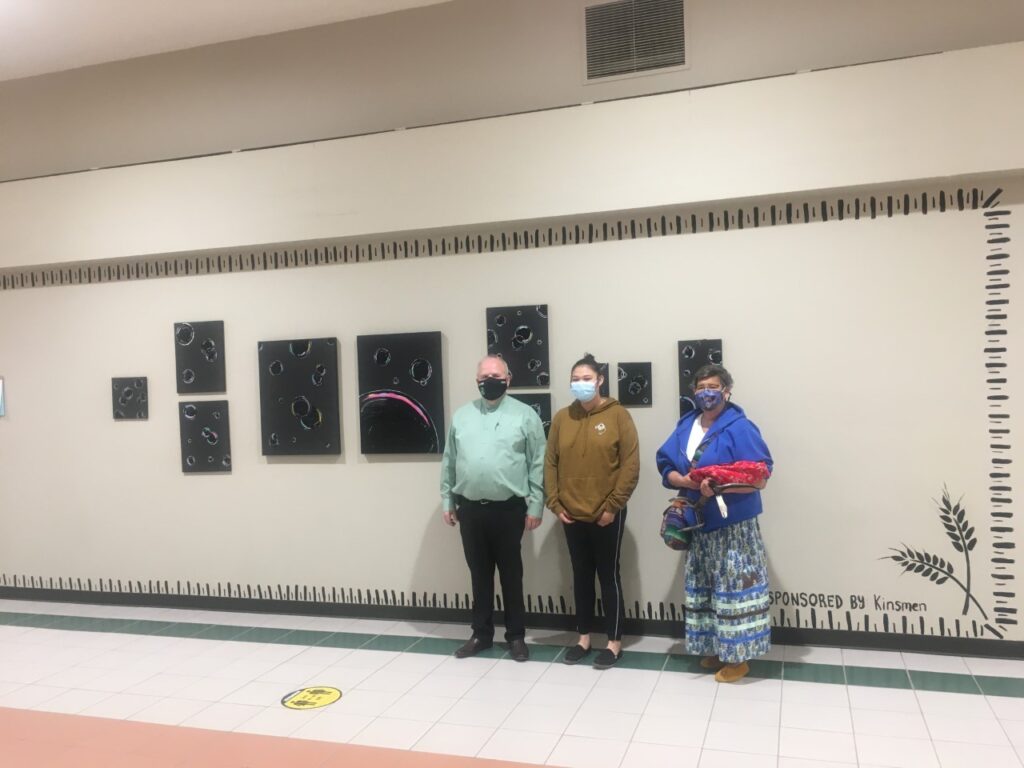

Settee, works as an Elder with Prince Albert Outreach but also advises the Prince Albert Police, Saskatchewan Rivers School Division, Community Building Youth Futures, Heart of the Youth Powwow, Mann Art Gallery, YWCA and Saskatchewan Impaired Treatment Centre. She knows discovering your connection to your culture isn’t a straightforward conversation. Rather, she says, it’s more of a lifelong journey.

It’s a journey she’s eager to share herself.

“I share that with my youth. Students in the classroom — they don’t see their teacher as maybe having a mortgage to pay, a husband and kids, all the other stuff. They’re a teacher, and that’s it,” she said.

“They don’t know how they got to become a teacher. It’s (also) true for elders. I share ‘ I came over from the other side, but this is what changed me. Part of that is just being able to help them when they’re in those dark times.”

***

Liz Settee’s ancestral roots are in Peguis First Nation, Manitoba. Her father was born in Cumberland House in Northern Saskatchewan. His dad, Liz’s grandfather, passed before he was born.

Liz’s dad spent his first six years in Cumberland House. His mom —Liz’s gran — got to know Mr. Deschambeault, who ran the paddle boat that ran back and forth between Prince Albert and Cumberland House. They got together and moved to Prince Albert.

Settee’s dad was sent to Residential School. He returned, but left for Europe to fight in the Second World War.

At that time, he was “enfranchised” — a legal process where a person’s Indian status was terminated, and they were given Canadian citizenship. According to UBC, it was a key feature of federal assimilation policies regarding Indigenous peoples, it was introduced in 1857 under the assumption that people would be willing to surrender their legal and ancestral identities to gain full citizenship and assimilate into Canadian society.

In the Indian Act of 1867, enfranchisement became legally compulsory for serving in the armed forces, gaining a university education or leaving reserves for long periods, such as for employment. Aboriginal women were enfranchised if they married non-Indian men or if their husbands died or abandoned them.

“My dad’s status was stolen by the country he was fighting for,” Settee said.

Once someone was “enfranchised” and their status lost, so too was that of their spouse and children.

While fighting in Europe, Liz’s dad met her mom in Dundee, Scotland. They wrote back and forth for 11 years. They didn’t become engaged until the death of Liz’s maternal grandfather.

They got married in 1956. One year later, Liz was born.

She grew up in her father’s home in Prince Albert, at 932 First Street East. The home is no longer there.

Liz attended Connaught School in Prince Albert, located between River Street and First Street and 10th and 11th Avenues East. It was built in 1913, the same time as Queen Mary and King George Schools, but was demolished in 1978. Connaught Village Housing Cooperative now stands in its place.

As someone with a darker complexion, Liz said she was picked on, and called a “half-breed.”

She wasn’t raised with her traditional, Indigenous culture.

“We were never taken to powwows,” she said. ‘We were never introduced to our culture.”

Liz said she was “forced” to attend church each Sunday. Her family to attended St. George’s Anglican Church, which was then located at Ninth Ave and First Street East.

Her mom had her first stroke when she was 15. Liz got married to the first guy she went out with. “I got married too young,” she says in hindsight.

Unhappy with her perceived responsibilities of doing housework, cleaning and cooking, Settee fell down a dark path, using alcohol and drugs.

She ended up in Vancouver. She working at the bar in the early 90s when she got a call from her brother.

Changes made in 1985 to the Indian Act meant that some who lost their status could get it back again.

Liz said her dad was reapplying for his status, which meant that she would get hers back, too.

“I was sitting on Robson and Granville one day, and there was a group of natives that were blocking the intersection and they were drumming,” Settee said.

“It was such an epiphany, because I remember sitting there going, ‘ I want to apply for my status cared, and I don’t even know what the issues are.’ It didn’t sit well with me.”

Settee decided that if she was going to get her status card, she had to give something back. She decided to go back to school, and applied at the Native Education Centre for their criminal justice program.

“I wanted to work with youth in trouble with the law,” Settee recalled. “That was my passion, right from where I applied at school.”

She was pushed to go into social work, but stood fast that she needed to take criminology, because she couldn’t manage the court system if she didn’t know anything about it.

“I ended up getting my certificate,” Settee said. “I was going to save the world.”

***

Vancouver’s Native Education Centre, now known as the Native Education College, was established in 1967 as a project to meet the educational needs of Indigenous people who relocated to Vancouver from their First Nations community. It became a private college in 1979, operated and controlled by First Nations. In addition to helping adult learners receive academic and life skills they need, it focused on cultural activities to provide a more supportive environment for Indigenous learners.

Settee, who was just beginning her journey to rediscover her culture, said each day would start with a smudging ceremony, a cultural and spiritual practice in many Indigenous cultures used to purify or cleanse the soul and to pray.

“The first smudge I had sparked my spirit,” Settee said.

“It lit a fire in me The more I learned, the less I knew.”

It made her want to learn more about her culture.

Today, working with youth who are in trouble with the law, Settee has found that many also have little connection to their culture.

“A lot of drummers have said that the drum saved their life from drugs and alcohol. I want our youth to grow up knowing about their culture.

She said this year, she met a youth through the powwow who wants to learn how to dance. She wants to learn the jingle dress dance “because she wants to heal the people in the land,” Settee said.

“Just sparking that is why I do what I do. I feel that if (youth) can find that spark, or that passion — or me, it was life-changing.”

It’s not just youth. While working on a project with Cheryl Ring and Tammy Leonard, Settee was approached by an Indigenous lady who was bout 50 years old, who asked her what smudging was all about.

“She left and came back half an hour later with another man. They both smudged. I got to sit and talk to them about my journey, and how I was taught, and what it meant. Anybody that wants to learn about their culture. Reach out. Don’t be scared to find somebody to talk to. Something’s got to change in this world.

***

That’s especially true right now, Settee said, as it’s a difficult time for Indigenous peoples in Canada. As more remains of more children are found at the sites of former residential schools, Settee said a lot of scars of shame and hurt have opened up again.

While non-Indigenous leaders seem more receptive to the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report now than they did when it was first released, Settee doesn’t think the country is really engaging in the real , and that today’s so-called reconciliation is anything more than skin-deep.

“This is the hard part. Yes, it’s all good, surface-y reconciliation,” she said;

“But what about our people that are in jail. Or our people that are still in the streets? Oh they’re lazy, why don’t they get a job? Once they start taking those people for human beings, and stop blaming them for their situating or where they are, that’s where the reconciliation is really going to start to begin.”

Canadian data shows that Indigenous peoples make up 30.6 per cent of the youth homeless population, and more than 30 per cent of the Canadian prison population, even though they account for about five per cent of the country’s population.

Reconciliation may be starting, but much more work needs to be done to reverse years of a concerted effort to assimilate Canada’s Indigenous peoples, and to strip away Indigenous cultures and practices.

Reconciliation, Settee said, “is a nice word. But I’m not sure that were even close to what true reconciliation looks like.”

***

The country may just be taking the first baby steps towards the level of reconciliation Settee says is needed, but Settee does hold onto hope that helping other youth reconnect with their culture can help redirect them from the same dark path of drugs and alcohol that she fell down.

Settee knows what the difference is between herself more than 30 years ago, and her life as the Elder and spiritual adviser now.

“What’s the difference?” I have a soul. I have a spirit. I didn’t feel that before,” she said.

“There’s a connection to something bigger than myself. Just having the privilege of being able to be in ceremony, different ceremonies. The lightness that I have felt.”

Settee says she sees miracles in the little things.

“I have a belief that everything in this world is connected as we as people are connected. I’ve always tried to be a positive person, and in my darker days, when I was a the first part of my journey, I didn’t have hope, and I didn’t have belief.”

She said it could be a picture, or a cloud that represent something, or finding a feather or a special stone.

“There are some people that won’t get this — some people will — but those are signs that somebody is walking with me.”

Settee hopes that in her work, she can help other youth, and adults, find that connection before they go down that same dark path.

“I do work with older people and families, and that’s just to be there for support or to help them through the times that they’re hurting,” she said.

“This residential school — the finding of those children — there are a lot of people hurting from that. Just to have somebody to talk to. I’m not saying I can fix everything or anything. Quite often that’s all we need, is somebody to talk to and listen. The big thing is the listening.”

Even if Settee can’t guide them back onto the light path, she believes that her journey, her message and ultimately that connection to culture, can start to nudge someone towards the right way.

“I’m not saying they’re going to automatically stop what they’re doing,” Settee says.

“They might not think of it today, or next week, or next month, but maybe a year down the road, it’s going to kick in and they’ll start thinking about it.

“Plant the seeds. That’s what I see myself as, a seed planter.”