Warning: This story contains details that can be upsetting to readers

Cowessess First Nation estimates 751 unmarked graves at the site of a former residential school on its territory in southern Saskatchewan.

The findings represent the first stage of research the First Nation started on June 2 — in order to locate, identify, and put a mark down honouring lost loved ones buried there.

“Removing headstones is a crime in this country and we are treating this like a crime scene at the moment,” Cowessess Chief Cadmus Delorme said.

“There are going to be many more stories in the future and this is Cowessess First Nation’s moment of our truth.”

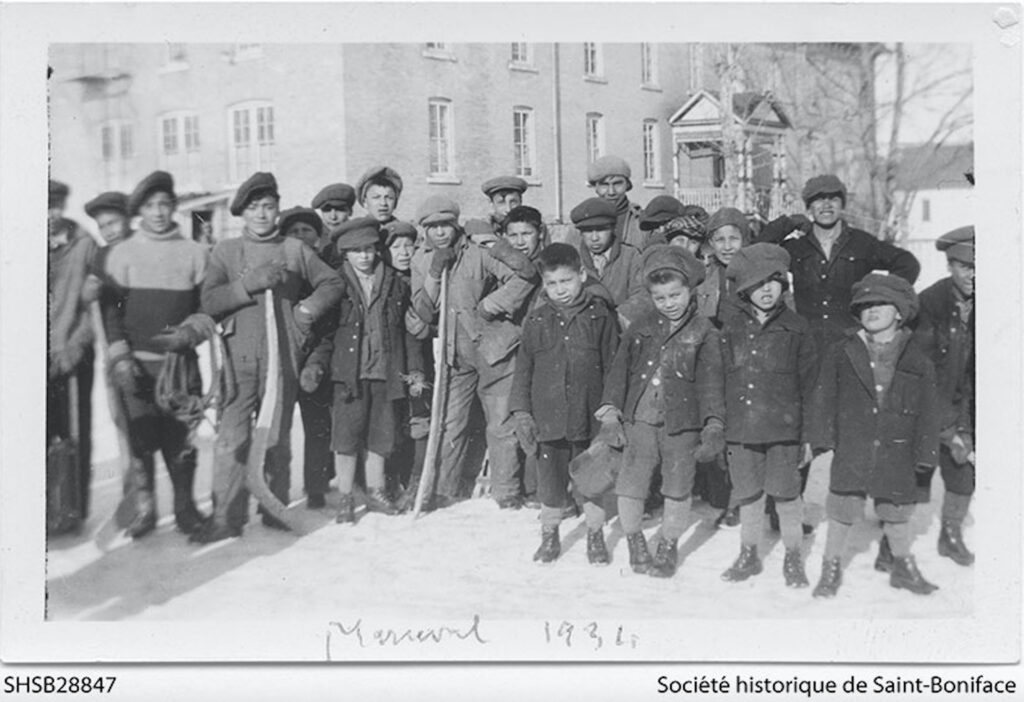

The Marieval Indian Residential School was founded by Catholic missionaries in 1898. Children who died there were buried at the nearby Catholic cemetery — that was run by the Roman Catholic Church from 1886 to 1970. The cemetery was given over to the community in 1970 and the school closed its doors in 1996.

Delorme said the church might have removed the headstones of more than 600 graves in the 1960s that remain unmarked to this day.

“We always knew that there was graves here,” Delorme said.

“The recent story of the Kamloops residential school has triggered many in this country. And we knew this was going to trigger as well.”

80-year-old Cowessess Elder Florence Sparvier was forced to attend the school as were her mother and grandmother before her.

“At that time if the parents didn’t want to allow their children to go to boarding school one of them had to go to jail,” Sparvier said.

She said nuns at the school treated them like “heathens” and “pounded” Catholicism into her family in order to assimilate them.

This robbed them of their physical, emotional and spiritual wellbeing.

“They were very condemning about our people,” Sparvier said.

“They were putting us down as a people so we learned how to not like who we were… When we became assimilated they made us think different and feel different. A lot of the pain that we see in our people right now comes from there… They made us believe we didn’t have souls.”

The Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN) which represents 74 First Nations in Saskatchewan recently secured funding from the federal government to conduct ground penetrating radar searches of residential school grounds across the province.

“This was a crime against humanity — an assault on First Nations people… The only crime we ever committed as children was being born Indigenous,” FSIN Vice Chief Bobby Cameron said.

“A lot of work and a lot of healing will take place. There are many sites that we are going to be doing similar work and we will find more… We are seeing the results of the genocide that Canada committed here. Genocide on our Treaty lands. We will find more bodies — and we will not stop until we find all of our children.”

We expect and demand a full, public, independent inquiry into the genocide… Our people deserve more than apologies and sympathies… Our people deserve justice.”

Cameron said Canada and religious institutions involved in the residential school system can start by handing over all records pertaining to the schools.

He said this is “just the beginning” of the number of Indigenous children who were lost and will be found.

“Canada will be known as a nation who tried to exterminate the First Nations. Now we have evidence. Evidence of what the survivors of the Indian Residential Schools have been saying all along for decades — that they were treated without humanity,” Cameron said.

“They were tortured, they were abused, and they’ve seen their classmates die. They even had to dig graves for their own fellow students. Can you imagine that? These stories will come out.”

Delorme said as the graveyard is marked, and further investigations are underway Canadians need to support Indigenous people by acknowledging and addressing the legacies of colonialism.

“All we ask of all of you listening is that you stand by us as we heal, and we get stronger. We all must put down our ignorance and accidental racism of not addressing the truth that this country has with Indigenous people,” Delorme said.

“We are not asking for pity — but we are asking for understanding. We need time to heal, and this country must stand by us… I ask you to open your minds that this country needs to have truth and reconciliation.”

Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe said in a statement Wednesday that “all of Saskatchewan mourns for those who were discovered buried in unmarked graves near the former Marieval Indian Residential School site.”

Moe said he has spoken with chiefs Cameron and Delorme to offer the “full support of the provincial government.”

“Sadly, other Saskatchewan First Nations will experience the same shock and despair as the search for graves continues across the province.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the hurt and trauma felt by Indigenous communities across the country is “Canada’s responsibility to bear.”

“While we cannot bring back those who were lost, we can – and we will – tell the truth of these injustices, and we will forever honour their memory.”

Trudeau promised continued funding and resources for Indigenous communities seeking answers.

Delorme said local catholic authorities have been cooperative with the investigation.

He further called on the Pope to make amends for what the Catholic Church has done to the Cowessess First Nation.

“The Pope needs to apologize for what has happened,” Delorme said.

“An apology is one stage of many in the healing journey.”

While Pope Francis has expressed “sorrow” following the discovery of the remains of 215 children at the site of the former Kamloops Indian residential School in B.C. the head of the Catholic Church has stopped short of an apology.

The Archdiocese of Regina confirmed that a local priest “bulldozed several grave markers” during a dispute with the Cowessess chief in the 1960s “in a way that we all find entirely reprehensible.”

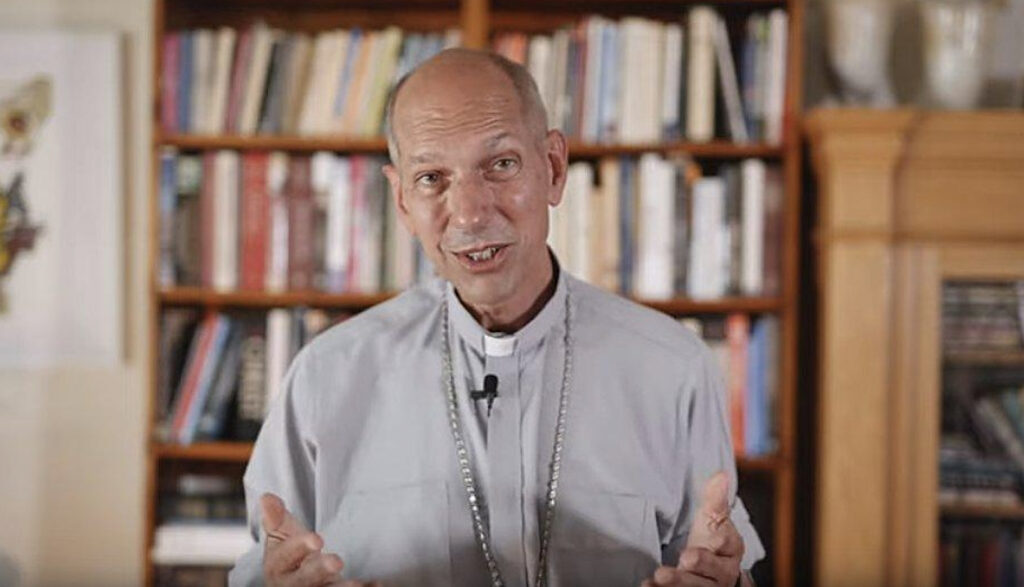

“I know that apologies seem a very small step as the weight of past suffering comes into greater light, but I extend that apology again, and pledge to do what we can to turn that apology into meaningful concrete acts,” Archbishop Don Bolen said in a letter to Delorme.

Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops President Archbishop Richard Gagnon said in a statement that Bishops fully support the investigative work underway and want to collaborate in the process.

“I find it very sad and disturbing to read about the uncovering of burial grounds at the former Marieval Indian Residential School in Cowessess,” Gagnon said.

“Bishops desire to accompany Indigenous Peoples and their communities through listening and actively working together to find solutions.”

Phase one of the Cowessess First Nation’s ground penetrating radar research in partnership with Saskatchewan Polytechnic covered the 44,000 square metres of the gravesite.

Delorme said as of Wednesday the radar registered 751 ‘hits’ which represent probable human remains with a 10 per cent margin of error that could be more or less.

Because only baptized children and adults could be buried in the cemetery the First Nation also needs to rely on oral history and written reports to locate unmarked graves in other places.

“If you weren’t baptized or if somebody had a baby that was maybe not old enough to be baptized there was a strong Catholic belief at one time that you couldn’t be buried in the grave site,” Delorme said.

“We do have some other locations on our First Nation that were orally told to us, and this is going to be years in the making.”

Chief Delorme said he hopes to one day locate all the missing people on Cowessess territory. In the meantime, people need to stay strong and support each other through the difficult reckoning that is now underway. He said old wounds are being reopened.

“The Roman Catholic residential school has impacted us intensely and today we… are feeling the first and second generation of that impact,” Delorme said.

“It’s going to hurt in the coming months.”

A national 24-hour Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available to support survivors and those affected. You can access emotional and crisis support referral services by calling 1-866-925-4419.